Reviewed by Daniel Barbiero

Reviewed by Daniel Barbiero

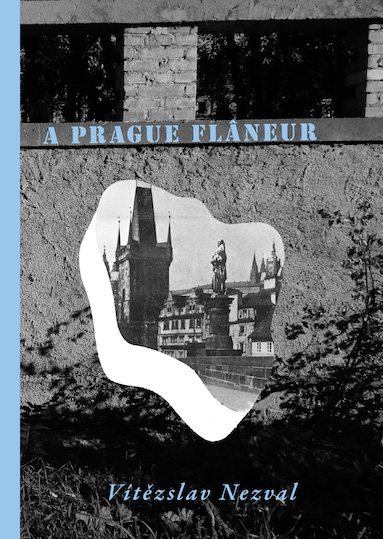

A Prague Flâneur

by Vítězslav Nezval

translated by Jed Slast

Twisted Spoon Press

November 2024, $19.00, 213 pages, ISBN: 9788088628002

For the Central European avant-garde, the interwar period was a time of both artistic exhilaration and political disaster. This surely was the case for Vítězslav Nezval (1900-1958), the Czech poet who helped bring the new avant-garde movement of Surrealism to his country in the mid-1930s, and ultimately abandoned it for Stalinist orthodoxy. His autobiographical essay and subjectively colored portrait of Prague, A Prague Flâneur, was written just before and after that break with Surrealism. An event of great personal importance, it provides both the context in which Nezval wrote the book and much of the book’s substance.

Interest in Surrealism in Czechoslovakia went back to the late 1920s. This was due in large part to Nezval, who at the time belonged to the Devětsil group, an association of Czech avant-gardists. Nezval’s poetry during this period reflected the influences of Rimbaud and Apollinaire, and already has surrealistic overtones. It was through the Devětsil group that contact was made with the Paris Surrealists, and in March 1934 Nezval, along with the painter Toyen (Marie Cermínová) and the art critic and theoretician Karel Teige, co-founded the Prague Surrealist group. In the spring of 1935 the leader of the Paris group, André Breton, together with fellow Surrealist poet Paul Éluard, was in Prague for a series of talks given at Nezval’s invitation; the visit led to close relations between the two groups, and a warm friendship between the Parisians and Nezval as well.

Among the Prague group’s activities was the translation of the Paris group’s works into Czech. Nezval translated Breton’s Communicating Vessels and was one of the three translators of Breton’s autobiographical essay Nadja, to which A Prague Flâneur bears a striking resemblance. Like Breton in Nadja, Nezval writes of his urban wanderings in search of the marvelous; he is a flâneur – an idle stroller along alleys and boulevards, observing the spectacle of urban life – in a distinctly Surrealist mold. He walks with no destination in mind while maintaining a state of disponibilité: an availability to chance encounters in which the seemingly miraculous erupts out of the mundane. He describes his “distinctive method” as consisting of “the interpretation of reality in a way that singularly embodies revelation through imagination” in order that “when we walk – and especially when we walk with no destination in mind – the faint images of our desire impose themselves on our steps…” These images provide the lens through which Nezval views Prague and records what he sees.

Much of the view is retrospective. The streets, bridges, buildings, and cafés “where Prague lives” provide a wealth of stimuli to which Nezval responds with a catalogue of memories. His Prague is like the site of an archaeological dig whose layers expose various periods of personal history. It also is the site of shops whose windows display goods that take on hallucinatory appearances, and the setting for chance meetings with strange characters and events that touch on the uncanny. Like Breton in Nadja, Nezval even happens upon a young woman who catalyzes a series of coincidences of personal significance to him.

A Prague Flâneur is written in a florid style, which Jed Slast’s translation vividly conveys. In addition, his endnotes are extremely useful for throwing light on the people, events, and places Nezval alludes to. We get a real sense of the deep emotional resonance the city held for Nezval, as well as of the personal turmoil his complicated relationships to Surrealism and the Surrealists, both Czech and French, caused him. Although throughout the book Nezval speaks very affectionately—indeed, effusively–of Breton, he nevertheless recognizes points of conflict between them. Nezval contests Breton’s poetics of pure psychic automatism and declares instead that poetry should synthesize unconscious desires and obsessions with conscious direction, intentional design with dreamlike content. He also rejects Breton’s position of condemning the Moscow purge trials and consequently refuses to sign Breton’s anti-Stalinist treatise “On the Time When the Surrealists Were Right.” His ruminations on these disagreements as well as on the tension between himself and the Prague group, which came to a head in March 1938, are pointed and tinged with self-justification. His language is by turns apologetic, defensive, assertive, reflective, and in regard to Breton, almost obsequious. These passages are about more than the trivial details of internecine sectarian squabbles; they are about the inner conflict Nezval was experiencing as he was writing the book.

Nezval wasn’t unique in being torn between artistic principles and political strictures. The 1930s were years of ongoing economic and political crises and evasions that created an atmosphere of emergency in which left-leaning artists like Nezval felt they had to take sides: for or against Trotsky; for or against Stalin’s USSR; for or against pacifism. The Spanish Civil War only increased the pressure and convinced many that the USSR alone, engaged in Spain in a proxy war against Germany and Italy, was committed to stopping Fascism, and never mind the increasing repressions perpetrated by Stalin’s regime. These matters were not merely theoretical for Czechs: the country was itself directly threatened by German aggression. While Nezval was writing A Prague Flâneur the Czech and German armies were preparing for war; he casually writes of “the daily droning of the bombers flying overhead” as he walks. Against this ominous background Nezval made his choice: for the Communist Party and Stalin’s USSR, and against the Surrealists and their denunciation of the Moscow show trials.

By the time A Prague Flâneur was completed, Nezval had broken with Teige over politics and declared the Prague Surrealist group dissolved. And yet in the book he denies that he is “one of those apostates who sobered up by parting ways with the Surrealist group” and even hopes that he could, with Breton’s “blessing,” continue Surrealist activities in Czechoslovakia on his own account. (Nezval’s correspondence with Breton during this period shows the same confusions and ambiguities.) But Nezval’s subsequent history saw him take another route: membership in the Communist Party, adherence to Stalinist orthodoxy and socialist realism, and a position within the official literary elite under the postwar Czech regime. It was a position he held onto until his death. In 1938 this was still to come, but we get a preview of it in Nezval’s paean to Stalin as the “simple, purely elemental, concrete, authentic figure” who “rises up before me as a savior.” Nevertheless, A Prague Flâneur remains as a fascinating relic of a time when Nezval could still look to aimless walking as the path to revelation.

Postscript: In an eye-opening appendix, Slast shows that a second, bowdlerized version of A Prague Flâneur exists. The second version, which Slast hypothesizes was made when the German takeover of all of Czechoslovakia seemed assured, cuts material that refers to Breton, Freud, Marx, Lenin, and other figures and events that the German authorities likely would find objectionable. Slast lays out the cuts and shows just how drastically the original text was disfigured. These gaps bear witness to the very real dangers those times held for artists and others.

About the reviewer: Daniel Barbiero is a writer, double bassist, and composer in the Washington DC area. He has performed at venues throughout the Washington-Baltimore area and has collaborated regularly with artists locally and in Europe; his graphic scores have been realized by ensembles and solo artists in Europe, Asia, and the US.