Reviewed by Justin Goodman

Reviewed by Justin Goodman

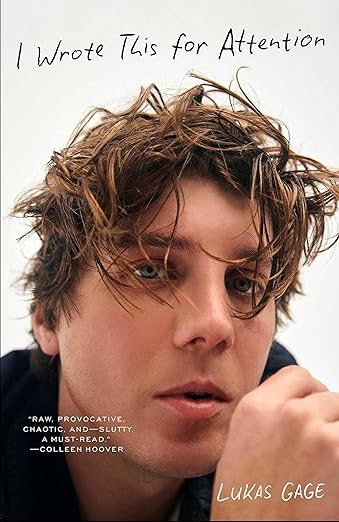

I Wrote This for Attention

by Lukas Gage

4th Estate GB

November 2025, Paperback, 320 pages, ISBN-13: 978-0008787769

Last decade, a reviewer at the Washington Post caused a kerfuffle after saying someone in their 30s is “too young to have undergone any genuinely interesting and instructive experiences…and too self-involved to have any genuine empathy.” This decade alone Julia Fox (at 33), Jeannette McCurdy (at 30), Evana Lynch (at 32), and Elliot Page (at 36) have all published memoirs. That’s to say, despite the best efforts of Jonathan Yardley, there’s a hunger to read (and become) early onset memoirists. Maybe this is because the smog of apocalypse hangs in the air and our corresponding asthmatic quivers compel us to wonder how we ended up in this guillotine, unbreathable world. Maybe, less dramatically, the memoir is compelling because it allows for under-represented stories to be told in a way that unites Storytime YouTube with mission statement. The personal is political: varying in a million little ways, all the above-mentioned memoirs share a sense that an individual life has revelatory power. The memoirist matters because the subject of the memoir isn’t the memoirist, but the forces that created them. Now, at 30, Lukas Gage has published I Wrote This For Attention: irreverent with a hint of self-aware smarm, the monologue of an aimless schmuck (complimentary) reveling in and leveraging being “’that one guy’—not famous, but slightly familiar.”

And reveling is the mood of I Wrote This For Attention. If it’s not the campy title, it’s the first sentence (“at the end of sixth grade, I killed a kid”—don’t worry, the kid is the “milk drinker” version of himself); if not campy and ironic, it’s blustery with witticisms like “Reno is the poor man’s Vegas…Laughlin is a degenerate Disneyland” and how his childhood best friends were “a slurred San Diego version of The Shining Twins.” Even after he’s begun to find success, being cast in White Lotus, discovering a healthier sense of self, he can’t help but compare the “circumstances of production” and the “amplified feeling of community” it provided with Lord of The Flies “If Piggy never lost his glasses and had access to room service and Infinity pools.” Which is to say, on a fundamental level, not Lord of the Flies. It’s all very carnivalesque, including the masquerade, the jumble of people and places, and a fan of any of Lukas Gage’s appearances from T@gged up to Overcompensating will enjoy his “not famous, but slightly familiar” sadboy Labrador Retriever energy paced by thoughtfulness. Honestly the best comparison to this sentimental and cavalier attitude is his prior foray into writing, 2023’s Down Low, a sex comedy inspired by the tragic first draft of Pretty Woman.

Beneath this, there is a man. There is an addict brother, sexual trauma, suburban angst, being abducted into a “wilderness therapy” program, an emotionally distant father, career anxieties. But Gage feels pressured by the revelry to say “I know I’m a self-proclaimed liar, but I promise none of this narration is unreliable.” And while he attempts to disclose the facts of his life—he’s quite chronological about it—you can sense a hint of resistance when, a little too pat, as if a cover letter to his reader, he winds down these experiences with phrases like “from watching the two of them, I learned…” and “It’s a lot easier to accept the mistakes your parents have made, than….” We don’t need blood, but I Wrote This For Attention feels unsure whether it’s flirting or having an affair, standing awkwardly between the rebellious romanticization of Down The Drain and the meditative commitment of I’m Glad My Mom Died. Even without referencing other celebrity memoirists, talking about his relationship to his job and marriage he leaves room for the doubt of “I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to stop feeling the gnawing, pathological hunger to prove my worth” and “It’s a chapter in a much bigger story.” His final words bluntly renounce social media attention: “I put down my phone.” Implied in them is his prior incompleteness.

Lena Dunham’s Girls protagonist Hannah Horvath, after learning her memoir is trapped in contract purgatory, grieves, “now what am I gonna do? Live another 25 years just to create a body of work that matches the one that they stole from me?” Such is the incompleteness in I Wrote This For Attention. It’s the incompleteness of someone who, newly arrived at the fantasized end of an obscure and persistent longing, is anxiously compelled to explain to themselves why it feels as if the longing rather than the labor were the entire point. It explains Gage’s lighter touch with his personal story too, for the memoir is less about what world would create Lukas Gage so much as how Lukas Gage would live in this world constantly stealing from him (time, freedom, family, etc). “I wasn’t running from my past; I was searching for something to shape the future,” as he puts his hard-earned lesson from AA. But this is the difficulty of a young memoirist: If it’s merely “a chapter in a much bigger story,” how lasting is the retroactive wisdom? The future hasn’t happened because the past isn’t over — as is clear when you discover this realization only halfway through the book, and over the hill is a marriage whose 6 month turmoil he will later state was the result of a manic episode.

And of his marriage, Lukas Gage admits “I was also dealing with a third presence in the relationship: the internet.” You can tell. I Wrote This For Attention is bathed in an internet affect and lingo (“Reddit rabbit hole,” “punchable face,” Luigi Mangione’s appearance). It explains a lot of the fear. While Yardley was wrong about 30 year old memoirists—they remain, despite the transhistorical grumbling of the elderly, people with experiences—it’s not unfair to distill from his crotchetiness the idea that we read memoirs to discover the commitments of other people. We become our commitments. The internet, an abundant, erratic, madcap attention machine, is a place of wary commitment and wary of commitment. When Gage talks about his “gnawing, pathological hunger to prove my worth,” he’s at his most compelling precisely because, as the memoir closes, you come to understand the internet is his ribcage. But as with everything internet-coded, he flees the potentially parasocial, the baring himself, for the lark, burned by the internet and approval hunger. By the final line we become him in his post-divorce trip to Iceland, looking up from the grief only to find “the Northern Lights—the one constant in this strange, icy night—were gone. Had they disappeared, or had I simply stopped seeing them?” Regardless of our glimpsing brief joys, laughs, and beauties, afterwards there remains the unease of the temporary. We put our book down.

About the reviewer: Justin D Goodman (they/them) is a writer based in Brooklyn, NY and a member of the New Haven Writers’ Group. Their work has been published, among other places, in Cleaver Magazine, Prospectus, and Prairie Schooner. You can find more of their work at JustinDGoodman.com