Reviewed by Jillian Damiani

Reviewed by Jillian Damiani

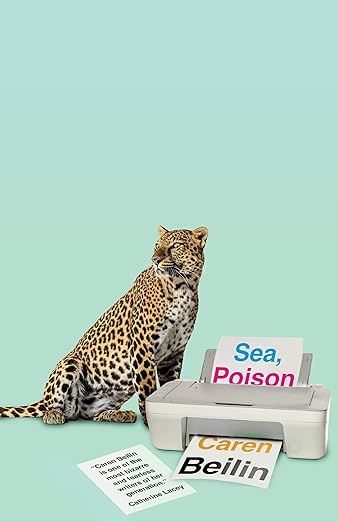

Sea, Poison

by Caren Beilin

New Directions

ISBN: 9780811239516, Paperback, October 2025, $15.95usd

Caren Beilin sticks to what she knows and loathes. Her latest autofiction, Sea, Poison, is another surreal critique of the medical industry’s subterfuge and villainy. With a sequence of homages to the 1957 novel The Sea and Poison by Shashuka Endo, Beilin and her characters experiment with Endo’s signature Oulipian constraints.

Cumin Baleen juggles writing and managing the autoimmune disease ravaging her hands. Mirroring Beilin’s oeuvre, Cumin’s work in progress is about gynecological rape, with allusions to Larry Nassar at Michigan State, George Tyndall at USC, and Mahendra Amin at an ICE facility in Georgia. Jumping between Endo’s novel on vivisection and contemporary instances of assault and sterilization, the violation of those in surgical gowns by those in scrubs is eternal.

A prerequisite eye exam for a new medication spirals into a coerced, deceptive surgery at the Moody clinic. Botched and reeling, Cumin questions the sanctity of the Hippocratic Oath in modern medicine.

Her boyfriend dumps her for their landlady, Janine, abruptly joins a cult led by a reclusive old man called Captain, and takes to eating Borax. Across town, Cumin rents a room that is actually a walk-in closet from sometimes actress, Maron. The apartment’s second bedroom, an unused office with an even more neglected printer, is guarded by a life-sized stuffed leopard.

Both despite and because of the sweeping, sincere critiques of medical and capitalist corruption, Beilin buoys her sea with tongue-in-cheek wit as well as humor, a hallmark of Oulipian writing. Every joke and turn of phrase maintains the novel’s brisk pace, an asset most well-executed when Cumin’s post-surgery mind sputters out choppy fragments.

The leopard itself is a dark joke: reminiscent of the one Maron’s father unleashed to hunt her through the streets of Philadelphia.

Describing Maron’s leopard attack, one character concludes: “ …because who knows how shit ends, best to put an axe in the ending, to split that leopard head before its right brain and left brain come together on some humanities / STEM bullshit.” Utilizing fourth wall breaks in vogue with modern media, Cumin’s most intimate developing relationship is not between other characters but with the readers.

Chronicling her autoimmune disease treatment in tandem with surgery recovery, Cumin quips, “I had stopped Xeljanz (alarming studies — death.”) Ironically, medication is a benign adversary in this story.

Hospitals abound in Philadelphia, more predatory than any leopard or pill. In an understated and incredulous whodunnit, those responsible for Cumin’s injuries steadily reveal themselves. Her discoveries are a welcome vindication for all victims of malpractice who are dismissed as paranoid or self-aggrandizing.

Cumin inserts excerpts and rewrites parts of Endo’s novel without the letters needed to spell ‘uterus,’ and returns to his descriptions of blood-drawing: the skin as a thin, easily punctured border between the essence of a body and those intending harm.

She obsesses over the concept of care and the innovative lengths people go to secure it. She fixates on Janine’s tamed and tidy hair:

She was smooth and important, and her dark curly hair, not dissimilar from mine, was managed it seemed with some kind of excellent oil, maybe of the coconut, I don’t know, but her hair was shiny and coily, and worn up in a kind of enviable barrette, the seething teeth of tortoise shell, that I was shocked — inspired, really — by the level of couthness that is after all possible. I felt really ashamed but had always found it so difficult — I do now — to get myself very much together.

Maron, too, is a source of envy. With lavish clothes and enthusiastic polyamorous sex, Cumin is fascinated by how Maron cares for herself without guilt. Even Captain, whom Cumin never sees or speaks to, is the beneficiary of support rather than a casualty of the negligent medical system. His followers feed him, attend to his bowel movements, and even make a mold of his penis in admiration.

Characters demand care, whether in relation to physical beauty, confidence, or necessary medicine. Their behavior is not anecdotal; it is defiant. Beilin asks: Who is worthy of care? Is anyone safe from the medical industry’s malicious exclusion and experimentation? How might a person decide to care for and about themselves when the powers that be discourage them?

Although Cumin is consistently misunderstood and disregarded by her acquaintances, people are always preferable company to hospitals. She knows people are the foundation of every city, and Philadelphia is under siege. Rather than humanity, what remains is “…a veritable sea of hospitals. The medical professionals in their blue and green scrubs aquamarize all of our city, at all hours. The flow of medicine, blood, and bedding. There’s poison.” Although Beilin’s characters are compulsively readable, plenty are complicit in the harm perpetuated by the medical industry. Does their indifference or active involvement in the medical world negate their personhood? Where does the sea part, and who may walk that path with Cumin?

Absurdity and humor may be the only way to combat the apathy and pervasiveness of the medical industry, the impinging poison. Laugh or drown. Sea, Poison, is holding its breath, and rather than a clean exhale of an ending, Beilin characteristically offers that maddening sensation of moments before a sneeze.

About the reviewer:Jillian Damiani is a writer based in New York City. She holds an MFA in Nonfiction Writing from Columbia University and was a finalist for the 2024 Susan Kamil Emerging Writer Fellowship.