Reviewed by Heather Campbell

Reviewed by Heather Campbell

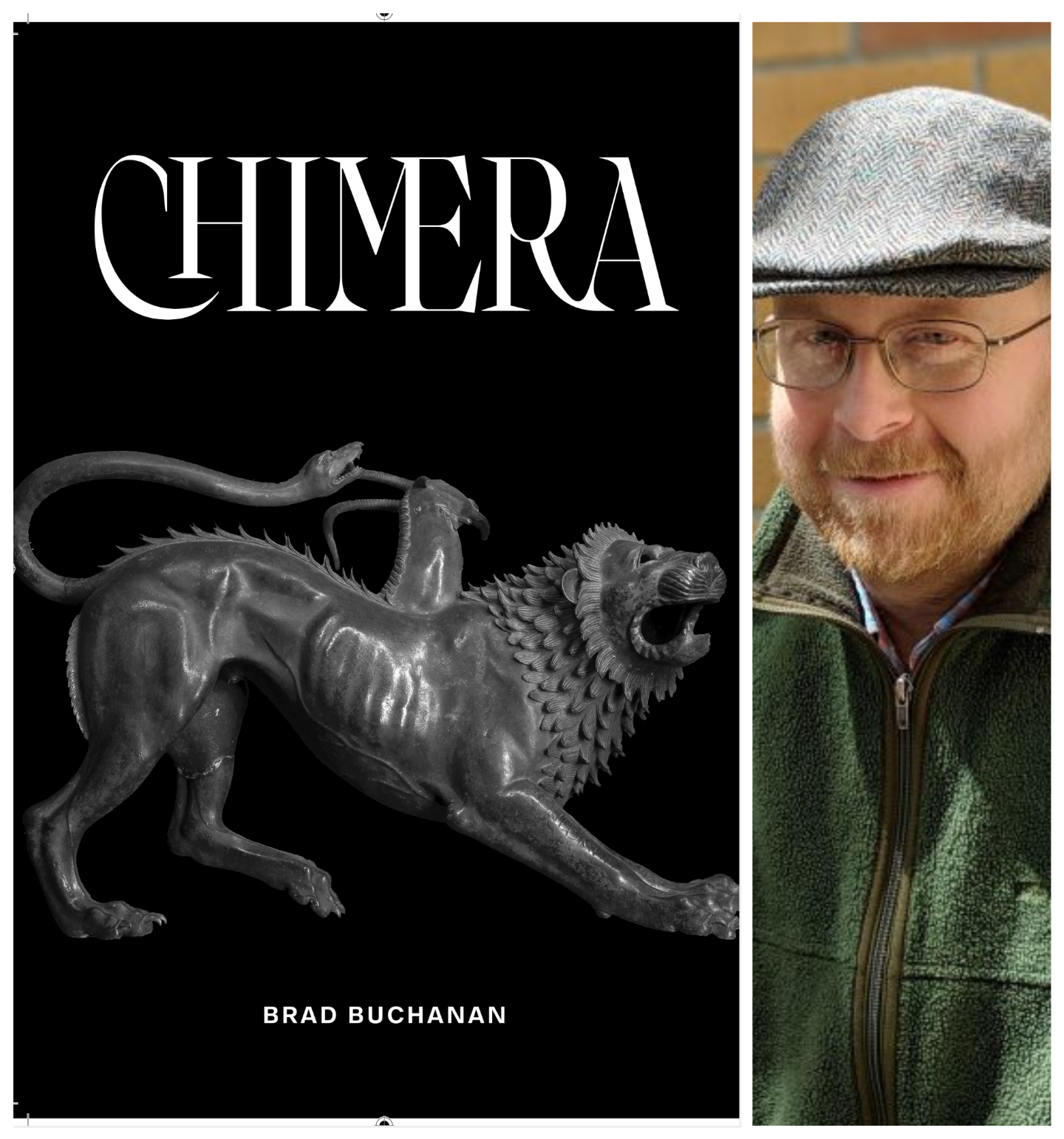

Chimera

by Brad Buchanan

Finishing Line Press

November 2022, paperback, 87 Pages, $19.99USD, ISBN 979-8-88838-039-0

A chimera, in Greek mythology, is a creature with a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and a serpent’s tail. More commonly, we use the term to mean an illusion, a deception, or something impossible to attain. In medicine, a chimera is a single organism which contains two different sets of DNA. I won’t pretend to have mastered the scientific basis of this, but it can occur when two embryos merge, or by transplantation, such as a bone marrow transplant.

Brad Buchanan’s collection Chimera gives us a story of the latter, while drawing deeply on both other meanings of the word – particularly the monster. Buchanan underwent a stem cell transplant to combat T-cell lymphoma; during treatment he experienced an acute graft-vs-host reaction and was then diagnosed with B-cell lymphoma brought on by Epstein-Barr virus. Chimera takes us through an account of multiple procedures and setbacks, presented alternately as invasions, imprisonments, and more bluntly, as betrayal by bodily function. His tone is uncomfortably straightforward, as though he is candidly refusing the reader’s sympathy even as he lays out the visceral details:

I have taken up residence

in a deep discomfort zone

just human enough

to make people squirm

(‘The Uncanny Valley’)

The image of invasion is strong throughout, be it via cancer cells or the graft-vs-host response, with commando raids, a roman battalion, ‘drones and cyber-terror’ all making appearances in these poems. To this invasion he is a prisoner, with small moments of reprieve:

the pills and liquids that held me hostage

let me out for a breath of fresh air

and even took off the blindfold for

a few blurry photogenic moments

later to be used in yet more ransom notes

(“The Day I Took No Pain Medication”)

The majority of Buchanan’s observation is trained on himself, but we do glimpse his surroundings, although much in the same way he glimpses them himself: during breaks in treatment when he is ushered outside by family or hospital staff. But we’re never far from battle. Even here we are as likely to see beauty as we are the dropped bones of the resident peregrine falcon’s prey. Of course, this entire collection isn’t exactly designed to be light subject matter, but Buchanan does allow humour onto his battleground. Dashes of fun make their appearance, from a poem entitled “Atrophy Wife” to the storm of illness being “like god’s own/overloaded dishwasher/flooding the kitchen”, to his observation of himself as a “monster perhaps/but one with a certain/historical imagination”.

Writing of illness can impose upon a reader something close to a doctor’s log of recovery and relapse, but the quick pace and straight-talk of these poems keeps us free of that trap. But a collection like this does request that the reader follow the plot, so to speak, throughout. It’s difficult to see many of these poems convincingly standing separate from the whole. But Buchanan has been here before, with a previous collection relating to his fight with cancer, as well as a ‘medical memoir’ of his graft-vs-host condition. So while the reader should be willing to enter a very introspective narrative, Buchanan has the craft to keep us engaged even as we seem to snoop into pages from his journal.

While the medical condition of being a chimera is obvious here, as well as the imagery of the monster that is illness itself, we’re left with the remaining definition of the unattainable, the illusion. It’s unfortunately easy to see, in at least part of the collection, that this unattainable state is recovery. But recovery does come. In “I Chose to Live” we encounter what Buchanan calls “the difficult rituals/of those who find/they are miracles”. We’re ushered to the conclusion of the collection with something that perhaps is not quite optimism, but close. In “Anemone” a walk on the beach presents this cautious hope: “It’s the deadliest beach in California,/ according to our elder daughter,/ but I don’t see it.”

About the reviewer: Heather Campbell is a Montreal-based poet with publications in Grain, Prairie Fire, CV2, The Capilano Review, and PRISM International. Her reviews have appeared in Grist, the Women’s Post and Dance International Magazine.