Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

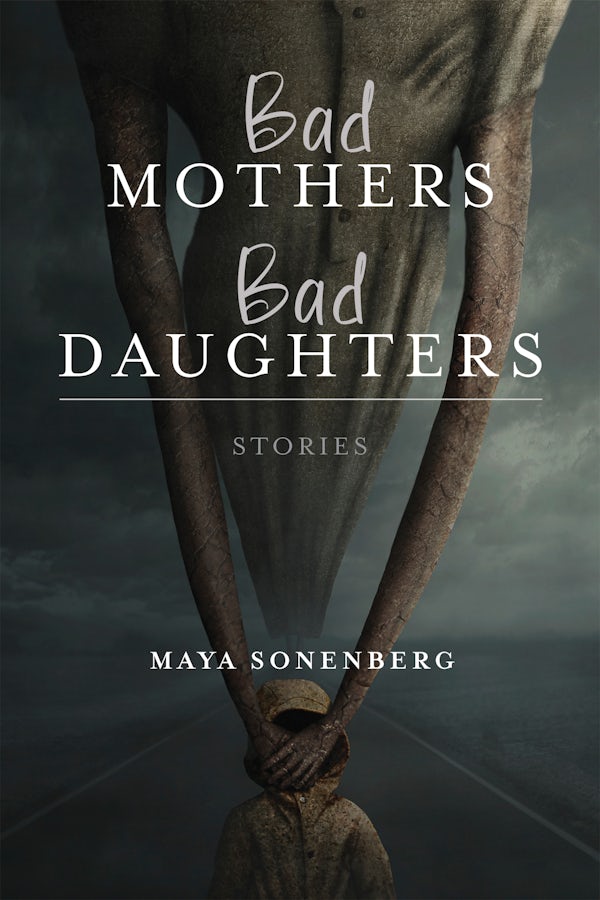

Bad Mothers, Bad Daughters

by Maya Sonenberg

University of Notre Dame Press

Aug 2022, $20.00, 160 pages, ISBN: 978-0-268-20302-3

The title of Maya Sonenberg’s new collection of stories tells us right away that guilt is at the center of these stories, mothers and daughters failing to measure up to their sense of duty to each other. As the reader gets into the stories, the fairytale nature of their shortcomings likewise becomes clear, giving these stories an air of fable – not a moral lesson so much as an insight into human frailties and failings, both mothers and their offspring, merely two sides of the same coin; a parade of characters who come up short.

Indeed, the fairytale aura of the early stories sets up the dynamic for the more realistic stories that follow. “Pink Seascape,” “Dark Season,” “Four Phoebes,” “Moon Child” – these initial fictions involve Disney-style princesses (albeit with a darker twist), temptresses, a Cinderella figure (“no Cinderella, she,” Sonenberg writes of Mona in “Moon Child,” but don’t believe the disclaimer!). The four phoebes used to be human sisters, until a giant kidnapped one of them and after much drama they became birds. “I am going to tell you the story of their kindnesses to each other,” Sonenberg writes, and already we can hear a mother telling bedtime stories to her kids. Storytelling itself is central to this collection. “Seventh,” which follows “Four Phoebes,” likewise involves sisters. Lolly is the seventh daughter following three pairs of twin sisters – which feels like something straight out of the Brothers Grimm. The plots of these tales take on a dreamlike inconclusiveness; a fever breaks, a dream fades like a mirage (“the relentless conversations between mothers and daughters that usually echo from the dressing rooms are gone, too,” “Dark Season” concludes. “Moon Child” ends: “Now this is a beginning!”)

“Princess of Desire” is a story that implicitly incorporates the dreamy unreality of fairytales, the fairytale princess, but cleverly brings in the detective story as well. The story begins: “I was merely his customer: that’s what she said.” It’s what the narrator tells the policemen who have come to question her. The death of a carpet merchant seems suspicious. An actress, the protagonist takes on new identities all the time, a trope Sonenberg uses throughout these stories, the shapeshifting protagonist.

The narrator describes her peripatetic life, an actress going from town to town, playing different roles, taking on new lovers. At first she is obsessed with the carpet merchant in her town, tries over and over to seduce him, but he resists. When she finally moves on, the one lover to whom she becomes attached, “a manufacturer and purveyor of pickles,” turns out to be the son of the carpet merchant, a discovery she makes in his shop one day long after their affair began. “In the manner of all stories, the surprising information came as a surprise,” the narrator tells us, and she elaborates on the art of storytelling: “she flipped through his desk calendar, or the mailman walked in with a letter she needed to sign for, or a fairy disguised as an old hag came in and told her….”

Another actress, Mina, features in four of the stories, involving her and her parents, Bernard and Judith Cooperman: “Annunciation,” “Disintegration,” “Visitation,” and “On Seeing the Skeleton of a Whale in the Harvard Museum of Natural History.” In these stories, parents and children fail each other time and again. The very fact that Mina chooses to become an actress is a disappointment to her mother. But it’s only as mother to her own child, Luke, the surviving child of her twin birth, that she understands the failure implicit in motherhood, a situation no less booby-trapped than being the child: doomed to be a bad daughter and a bad mother… The deck is stacked!

The very first story, “Childhood,” draws this sharp distinction. Remembering her childhood, the nameless protagonist – the mother – flashes on the Barbie dolls she used to color up with Magic Markers. As a child, she’d thought of the markings as decorations, “but now, a mother, she thinks of them as bruises and is aware, too, that if she weren’t a mother, she might just think of them as tattoos.”

“Painting Time” is a story about a man and woman juggling their lives as artists with their lives as parents. “She feels like Jimmy Carter, trying to get the Israelis and Palestinians to negotiate.” It’s more difficult for the mother. Her husband eventually becomes a successful painter, while she struggles. But at the end, when somebody asks her if she would have traded her children for a show at the Seattle Museum of Art, her answer is an unequivocal no.

Reminiscent of Philip Roth’s novel, American Pastoral, the story “”Return of the Media Five” follows another woman whose identity keeps changing. “Susan” is on the run from the FBI after an SDS-like theft of government property. We follow her through the years, running away, eluding capture, changing her name and ID, until, at the end, she finds herself pregnant, and her resolve changes…. “Seven Little Stories about 1977” similarly involves a rebellious daughter, Anna. Curiously, there are several stories that feature “Anna,” but unlike the Mina character, each seems a different person. Or is this just part of Sonenberg’s shapeshifting magic?

A number of the stories involve Jewish characters and their complicated feelings of obligation to parents and to children. In one, “Last Week, New Year,” which takes place during Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, a day implicit with guilt, Anna’s mother has died, and her head echoes with her mother’s final words: “Promise me…” … that she will attend shul and say Kaddish for her, that she will throw nothing of her mother’s possessions away, etc…. She’s already proven herself a failure in never having married or produced grandchildren.

Another “Anna” compares sons and daughters with her friend Martha, in “Hunters and Gatherers,” two young mothers beside the pool on a summer’s day. In footnotes, Sonenberg cites studies about the male and female of the species (and chimpanzees).

“Will plot necessitate that something more happen than a frog emerging from a pond?” the narrator of the final story, “Forest,” asks. Plot and character are both fluid throughout this remarkable collection. Only guilt is a reliable constant.

About the reviewer: Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore and Reviews Editor for The Adirondack Review. His latest book, Catastroika, was published in May 2020. A chapbook of poems, Jack Tar’s Lady Parts, is available from Main Street Rag Publishing. Another poetry chapbook, Me and Sal Paradise, was recently published by FutureCycle Press. An e-chapbook has also recently been published online Time Is on My Side (yes it is). Another chapbook, Mortal Coil, is forthcoming from Clare Songbirds Publishing.