Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

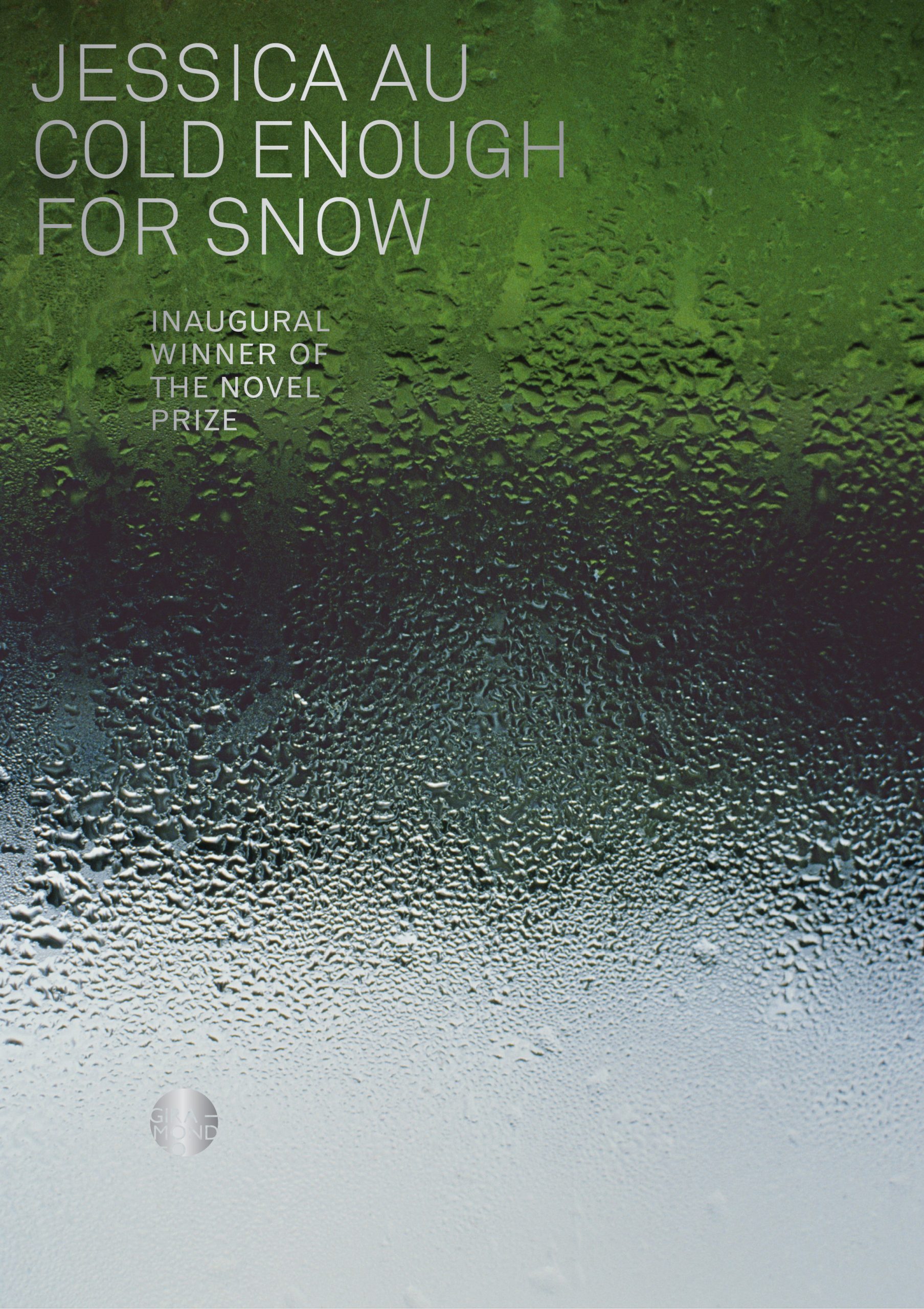

Cold Enough for Snow

By Jessica Au

Giramondo

Feb 2022, 108 pages, Paperback, ISBN 9781925818925

Jessica Au’s novel Cold Enough for Snow is a delicate, beautiful book. The novel, written in spare, luminescent prose, opens at an airport in Tokyo, a light, fine rain falling on the narrator as she picks up her mother for a holiday. We know the mother was born in rural China, and was brought up in Hong Kong before migrating with her family to an English-speaking country, and that the daughter and the mother now live in separate cities. Other details are revealed through the book, but do not tell us specifically where they live now, their names, or the cause of their various migrations. Nevertheless, these unspoken facts form a key part of the narration, colouring the work with implicit meaning that unfolds subtly as the story progresses. Fom the first page, a sense of loss infuses the novel. There is no point in the book where we are told that the mother is not well, but she is clearly ageing, and there are hints that time is running out: “We did not live in the same city anymore, and had never really been away together as adults, but I was beginning to feel that it was important, for reasons I could not yet name.” (2)

These signals continue through the book as the mother’s frailty becomes apparent through what she declines to do: waiting outside a gallery instead of walking through it, leaving her hiking boots behind so she cannot go on a mountain walk, struggling to put on a shoe, and through the tiredness that is becoming apparent in her face. The mother and daughter travel together through a landscape that is known to the daughter but rendered unfamiliar through a deliberate attempt to see things with fresh eyes, mindfully, as if everything depended on noticing those small moments:

I recognised the form of everything – buildings, overpasses, train crossings – but in their details, their materials, they were all slightly different, and it was these small but significant changes that continued to absorb me. (3).

The mother’s perspective is revealed through the daughter’s perceptions, a view filtered by a combination of guilt, compassion, longing and callowness that is self-aware enough to feel more elegiac than immediate. There is a tension between the mother’s own acceptance of her increasing frailty and the daughter’s desire to keep moving forward (“like applying a kind of firm but gentle pressure”, 24). This tension charges the book and creates a strong momentum as the narrator strives to connect with her mother and simultaneously resists the opportunity for intimacy when it is presented:

The best we could do in this life was to pass through it, like smoke through the branches, suffering, until we either reached a state of nothingness, or else suffered elsewhere. She spoke about other tenets, of goodness and giving, the accumulation of kindness like a trove of wealth. She was looking at me then, and I knew that she wanted me to be with her on this, to follow her, but to my shame I found that I could not and worse, that I could not even pretend. I instead I looked at my watch and said that visiting hours were almost over, and that we should probably go. (59)

The tension is mirrored by the daughter’s inability to capture her mother on camera in “ordinary time, when she was alone with her thoughts”. (6) Throughout the book there is a sense that time is not fixed, and that the present is only another memory remaking itself in each moment. It feels as though the mother is present and absent at the same time. When the mother actually disappears, the innkeeper says he cannot recall there even being a second person. The mother’s re-emergence provides relief, but she comes out of the cold ghostly, further adding to the sense that the mother’s presence is ephemeral:

When my mother finally appeared, she might as well have been an apparition. She came with her puffer jacket zipped up to her chin, and in the cold night air her breath came out in a little cloud, like a small departing spirit. (90)

The narrator’s memories of her boyfriend Laurie, her time as a student looking after a teacher’s house, her work as a waitress, her sister’s trip to Hong Kong, and recollections of her mother’s memories of her uncle, form digressions through the narrative present. These stories are presented as somewhat unreliable (“she had frowned and said that nothing like that had ever happened”, 48) but the digressions feel as natural, evoking the stories we all carry around with us. This relationship between memory and action creates a powerful conjunction between the familiar and unfamiliar, something that is picked up by the multiple focal points: a meticulous attention to detail, the varied senses of home, the unspoken mother-tongue of Cantonese, and the impact of dislocation reverberating across generations. We become increasingly aware that there are multiple layers of existence, where adjustments between the known and the unknown are always taking place–memory weaving its way through perception. Meaning happens in these tensions – it is enough to “simply to see and hold them.”:

It occurred to me that by the age I was now, my mother had already made a new life for herself in a new country. She would have, by then, already become mother to a new baby, and would likely have been able to count the number of times that she would return to Hong Kong to see her family on the one hand. I tried, and failed, to imagine her first moths there. Had she been homesick? Had she been awed by the streets, the brick and weatherboard houses, so different to her own home? Had she been worn out not by the big changes, but, as is often the case, by countless smaller ones—the supermarkets that were so well stocked, but where you could not buy glass noodles, or the right kind of rice; the homes where porridge was something plain and tasteless, made with oats and milk instead of with thinly sliced scallions, bamboo shoots, and black, hundred-year eggs; the roads where people shouted at her from cars when she crossed the street, for reasons she could not yet understand the bank teller unable to understand her near-perfect, colonial English? (39)

In this way the book takes on the shape of what it explores philosophically. Time becomes unfixed through art, able to recreate, re-contextualise, and transcend the limitations of the clock. This metafictional quality is handled as subtly as everything else in the book, obliquely, as when the narrator visits a gallery to see Monet:

They had seemed to me then, as now, like paintings about time. It felt like the artist was looking at the field with two gazes. The first was the gaze of youth, awakening to a dawn of pink light on the grass and looking with possibility on everything, the work he had done just the day before, the work he had still to do in the future. The second was the gaze of an older man, perhaps older than Monet had been when he painted them, that was looking at the same view, and remembering these earlier feelings and trying to recapture them, only he was unable to do so without infusing it with his own sense of inevitability. Looking at them, I felt a little like I felt sometimes after reading a certain book, or hearing a fragment of a certain song. (69)

Cold Enough for Snow is a deeply beautiful novel, richly potent in its themes, while resisting simple explication. It reads quickly, driven forward by the tension between presence and absence, love and shame, caring and being cared for, past and present, belonging and otherness, while its meaning unfolds slowly, lingering.