Reviewed by Susan Francis

Reviewed by Susan Francis

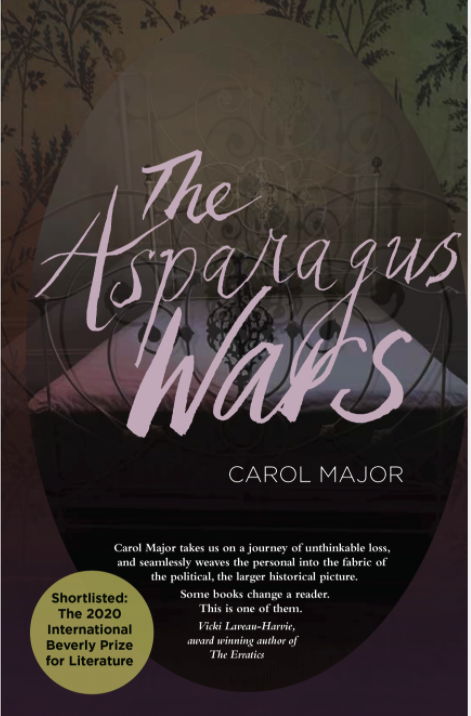

The Asparagus Wars

by Carol Major

Spineless Wonders

October 2021, ISBN 978-1-925052-66-4

At its heart, The Asparagus Wars details the devastating story of Carol Major’s young adult daughter, who lives with Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, a rare form of the degenerative disease. In the cruellest of ironies, this young woman also contracts bowel cancer and dies awfully from something nobody ever expected. Major documents this experience with her face turned directly into the gale, sparing no-one, especially herself. And she writes like a poet, using evocative imagery seemingly created from nothing much at all: Yellow daisies grow along the wall and inside it smells sweetly of drying clay (a description of the small cottage in France where she is writing her book). But beneath the telling of the tragic mother-daughter relationship also lies a feminist work both intimate and confronting in its courageous examination about the societal shaming of women.

Consulting at Varuna – the National Writers’ House, situated in the Blue Mountains of NSW and one of the foremost institutions for literature development in Australia – Major is appreciated by all the writers she works with and entirely well respected. Softly spoken and intellectually generous, she has an instinctive ability to grasp an emerging author’s intent; wise and gentle in the way she imparts her incisive advice. She was raised in Canada, has a Doctorate of Creative Arts from the University of Technology and her short stories and essays have been published in both Australia and her mother country. Her sister is the renowned Canadian poet, Alice Major. The Asparagus Wars, released in Australia by Spineless Wonders, October 1, 2021 and printed by Ingram Spark in North America, is Major’s debut memoir.

There are different kinds of book review. One in particular demands objectivity, using a critical lens to analyse themes, relevance and style – a separation of self. This review is not that kind. Compelled by a strong identification with Major’s experience of marriage and motherhood and a familiarity with the power structures that discriminated against her – remembering the marginalisation I’d faced as a single woman raising a child on my own – I came to the gradual understanding that my interaction with her work was almost wholly personal. My instinctive response to The Asparagus Wars, Major’s powerful recounts of gendered inequality, made it undesirable that I interact with the book in any other way.

If that was not enough, I also knew that Major had assessed my own memoir – a shameful search for a set of shifty biological parents and the traumatic death of my husband – and on calculation, I figured it was only a few short months after finishing her own work. That got me thinking about the exact time she might have allocated to writing about relinquishing her baby. During what season had her daughter died so tragically? And the writerly self-absorption I was well aware I owned, knocked me hard. What came to mind was the fragile tissue paper dress patterns were once made from and the way my mother sewed the clothes I wore as a girl. I felt as if the two stories had been cut from different sides of the same cloth.

As a reader, and someone who’d talked to Carol Major for maybe two hours across Skype, a sense of rage and recognition began building about the bigotry she’d suffered. How, as a pregnant teenager and later a single mother she came to perceive herself as unacceptable – I would have happily been dragged up to the alter in sackcloth and whipped. All the shame… shame is the feeling there is something wrong with you. Much of the book is weighted with this personal touchstone: I was found wanting as a mother long before you came along.

I remembered the time my own baby refused to breastfeed. In despair, and against the wishes of the midwife – ‘persistence is key, dear’ – I took the baby to a male doctor, only to be accused of starving my son and informed I was lucky to leave without a call being placed to child welfare. It was years before I could discuss this incident without bursting into tears. I was also reminded of the novels I’d devoured as a young woman, written by second-wave feminists from the mid-twentieth century. Marilyn French’s The Women’s Room and Margaret Drabble’s, The Millstone. Here, similar acts of degradation against women were laid bare. Time had passed, but not so perhaps, the practice of shaming young mothers. Nor the constant painful memories.

Settings in The Asparagus Wars shift backwards and forwards from France (later). And to the story of Major’s daughter (before). The switch is achieved effortlessly and allows for a wider shot of Major as protagonist. The title refers to a regime believed by some in her family as essential practice to keeping her daughter alive – special anti-cancer procedures (coffee enemas) and a diet that includes blended vegetables. The Asparagus Wars also represents the worst of the First World War battles fought in the Marne region of France, where part of the book was written. And Major’s search for the graves of the ‘bad’ soldiers – the ‘others’, the ones blindfolded at dawn (she feels a strong empathy for these young men, as do we). Analogically, it is the desperate war a family fights attempting to cope with the unimaginable: Your gastroenterologist, an older man with eyes like a faithful dog, kneels in front of you. A young woman with skin as translucent as bone porcelain is at my back. She is a surgeon. She says she will go ahead and perform a colostomy without general anaesthetic because you are going to die now if nothing is done.

But such a title, with its reference to a vegetable visually impressive in its greenish length and limpness must also underscore another concern – the calling-out of all those small, pathetic (patriarchal) positions both men and women occupy: ‘sides’ that are seemingly so crucial to our sense of who we are, choices we make to cement our superior place in the world.

When Major was seventeen, preparing to give birth in a home for unwed girls in Canada, a nurse chooses to tie Major’s arms down: she is thin, blond, all tucked in and fastening my hands in straps… ‘Haven’t you done enough damage already?’ Similarly, during the endless and vicious battles waged by Major’s first husband and his second wife over custody of Major’s children, even the ones yet to be born: your father and Lillian loom, their flushed faces spitting out something to do with me not having breakfast cereal in my cupboards … ‘That woman is not fit to be with children. When that baby is born it should be taken away.’ Repeatedly, Major exposes these commonplace, unnecessary cruelties. The pointless, savage wars men and women fight. The pain we force upon each other. The sheer inhumanity of it. Major’s elegiac writing style, gently probes these inconsistencies in amongst a visceral story of disability and death and forces us to note how such modest progress has been made. A mirror of my life. Your life? All of us made to suffer so, for independent thought.

Any woman will recognise this story, any woman who has ever been screwed over by an ex, summarily struck off a list by some officious pen-pusher at a welfare centre, shamed and threatened with the unthinkable by a medico. That unnecessary attitude harnessed against single mothers living in poverty, especially when they choose to ignore cultural expectations. It was then, as it is now. And still as senseless as a war raged over a bunch of asparagus.

I have always respected and admired Carol Major. I will be forever grateful for her guidance and generosity of spirit, responsible, in some measure, for the publication of my own work. Reading The Asparagus Wars, I am reminded of the strength an honest and humble voice holds in making memoir, the lyrical use of language and the courage it takes to create an extraordinary work of art.

Dr Carol Major’s memoir, ‘The Asparagus Wars’ is available in Australia (through Spineless Wonders) and North America, printed by Ingram Spark. It was shortlisted for the 2020 International Beverly Prize for Literature.

About the reviewer: Susan Francis’ memoir, The Love that Remains, was published in Australia by Allen & Unwin in 2020.