Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

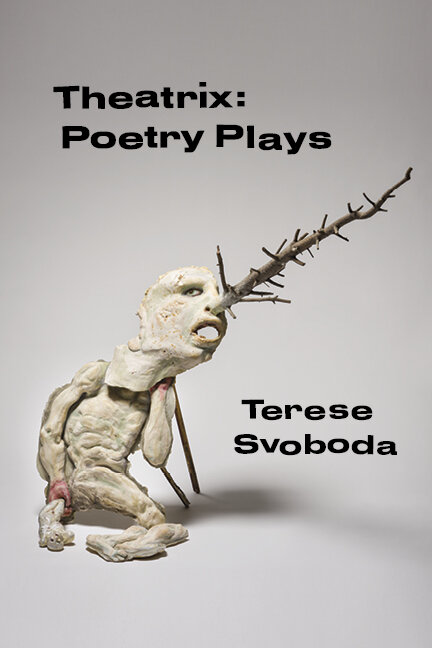

Theatrix: Poetry Plays

by Terese Svoboda

Anhinga Press

March 2021, $20.00, 84 pages, ISBN: 978-1-934695-69-2

Just as Alan Michael Parker writes “An Introduction in the Style of an Introduction” to Terese Svoboda’s Theatrix: Poetry Plays, so Svoboda’s new collection of poetry is written “in the style of stage drama,” full of word play and humor, though, for better or worse, not exactly conforming to Gustav Freytag’s five-part dramatic pyramid (exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, denouement). But lots of fun, regardless! Witty, irreverent, provocative. As The Bloomsbury Review noted, Svoboda is “one of those writers you would be tempted to read regardless of the setting or the period or the plot or even the genre.”

Svoboda alludes to Shakespeare, the great dramatist, over and over again in these poems, from Hamlet and Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet to King Lear and Henry VIII and Julius Caesar. The poem “A Tripod Provides Stability Against Downward and Horizontal Forces” begins with an epigraph from Macbeth (“By the pricking of my thumbs, / Something wicked this way comes.”), and a poem called “The Scottish Play” likewise alludes to Macbeth. It begins:

a soliloquy piped in over the vacant stage

[b.g. sound: ice cubes] [coffee pouring]

someone says words and then you see “tomorrow” and “tomorrow” and “to-

morrow”

rephrase at lights out: “the instruments of darkness tell truths”

Svoboda’s background in video is evident here in the very “visual” nature of the poetry she writes, complete with stage direction and what almost feels like a camera trained on the action, establishing shots narrowing to extreme close-ups and pulling back again.

Svoboda’s allusion to King Lear highlights her penchant for word play. The poem is entitled “King Leer,” and paints a picture of the mad king as a kind of “dirty old man.” He still fumes with his resentments but seems even more confused than Shakespeare’s protagonist.

By day and night she wrongs me.

The fool laughs as if Dad’s joking.

Of course a king’s esteem is inflated.

Pump the dog’s stomach for Viagra,

hear Let me alone but don’t leave me,

your mother is dead, but you will do.

The “dad” figure recurs in these poems, from “Dad or God?” which opens part two (“Act Two”?) of Theatrix: Poetry Plays, to the prose poem, “Dark Daddy” (“The dark daddy went about the hushed place in a turncoat. You can suspender him, said the allegory, the one moralizing that such a dad wasn’t Good-for-the-Planet, that such a dad had better watch his feet in said place. The place pivoted and the dark daddy went down.”). Svoboda may be going after the patriarchy here, or is she simply having fun? Catherine the Great makes an appearance in “Dad or God?”: she “bade dwarves to copulate on ice, / then stay the night in her frozen / palace.”

Svoboda alludes to a bunch of other stage productions as well as Shakespeare, from Sheridan’s 18th century comedy of manners, The Rivals, featuring the unforgettable Mrs. Malaprop (“To illiterate him quite from your memory” is the epigraph to one of Svoboda’s poems), to Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides (“House of Atrium” is another clever word play on the House of Atreus, subject of so many Greek tragedies). “Usher” is a poem written in stageplay dialogue form (as so many of these poems are), involving Edgar Allan Poe and Claude Debussy. The poem alludes to Debussy’s unfinished opera, La chute de la maison Usher based on Poe’s 1839 short story, “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

POE: Mr. and Mrs. Luke Usher, the friends and fellow actors of my mother who took care of me while she died.

DEBUSSY: I died, writing the Poe opera. [Colon cancer].

Madness, resurrection, the living twin of the buried girl, plus opium, opium, opium: a knell.

“Emma’s Play” features Emma Goldman. Specifically, the characters of four former lovers (unnamed) gathered around a coffin containing Emma’s corpse, in dialogue with one another.

Many other poems involve the trappings of drama and the theater. There’s a dramatis personae at the start, the cast “in order of appearance” – though it feels incomplete – which includes Jack Benny, who does make an appearance in the first poem, “Stage Manager: Lights Up.” Several poems later comes “The Cast.” But this “cast” refers to an actual cast a man in the audience wears, as he interacts with an “old comedienne” up on the stage.

She sighs. [Always the competition]. Sex and death are my two best subjects, she says. She tells him with death you can do it alone and nobody laughs at you.

“No Props” (which follows “Malaprops”), “What? is your line,” “Silverware Dialogue,” “Moon Theater,” “Emergency Exit,” “Chair Theater,” “Backstage: Fear Ducts” and “Spectacle” are other poems that take off from theater lingo. “DXM as Bond,” referring to that magical get-out-of-jail-free device from Greek and Roman theater, Deus ex Machina – “a god from a machine,” the crane that brought actors playing gods over the stage – likewise alludes to the theater in characteristic word play fashion.

Svoboda’s verse is playful, a true delight. As Alan Michael Parker writes in his Introduction in the style of an Introduction, “…give us voices, and their own inner voices, the ways we have made gender our playmates, and how we make our bodies the play. Then stand close, and watch the players play.”

Brava! Encore!

About the reviewer: Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore and Reviews Editor for The Adirondack Review. His latest book, Catastroika, was published in May 2020. A chapbook of poems, Jack Tar’s Lady Parts, is available from Main Street Rag Publishing. Another poetry chapbook, Me and Sal Paradise, was recently published by FutureCycle Press. An e-chapbook has also recently been published online Time Is on My Side (yes it is). Another chapbook, Mortal Coil, is forthcoming from Clare Songbirds Publishing.