Reviewed by Ruth Latta

Reviewed by Ruth Latta

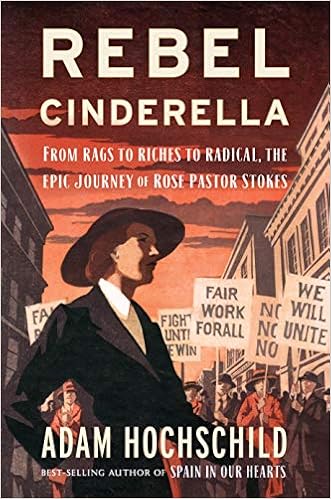

Rebel Cinderella

From Rags to Riches to Radical,

The Epic Journey of Rose Pastor Stokes

by Adam Hochschild

HMH Books

SBN-13: 9781328866745, 03/03/2020, 320pgs

In Rebel Cinderella, journalist/historian Adam Hochschild presents American working class history in the first decades of the 20th century through the remarkable story of an activist, Rose Pastor Stokes. Born in imperial Russia in 1879, deserted by her father, two year old Rose was brought to London, England by her mother, who found work with a tailor and a home in an East End tenement with family members. There her mother met and married Israel Pastor, who sought his fortune in the United States and brought his wife and stepdaughter to America. He was unable to support the six children he had with Rose’s mother, so at age eleven in 1890, Rose went to work in a Cleveland, Ohio cigar factory.

Though she received little formal education, Rose loved to read. A letter she wrote to the Jewish Daily News in New York City led to a job offer as a columnist and reporter, which paid twice as much as the cigar factory. At that time, New York and other American cities were teeming with immigrants, living in slum conditions in an era with no social safety net. The Settlement House movement was an upper class effort to help newcomers with literacy and vocational training, medical help and some of the services of community centres. The University Settlement House in New York was one of many such projects. When Rose’s editor sent her to interview board member, Graham Stokes, Graham and Rose fell in love.

Graham, a Yale man who had graduated from Columbia medical school, had been pressured by his father to join him in managing the family enterprises, which included real estate, mines and banking in Nevada, and the Nevada Central Railroad. He was related to the wealthy Phelps and Dodge families as well, and was part of the Eastern seaboard elite. Graham’s father could trace his ancestry back to the Plantagenets, and his mother’s ancestors had been governors of Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut in colonial times. The Stokes mingled socially with the banker J.P. Morgan and the railroad baron Cornelius Vanderbilt. Theodore Roosevelt and the Stokes moved in the same circles.

Hochschild believes that Graham found in Rose some quality lacking in the young ladies from his own background. Rose wrote that she found Graham “Lincolnesque, earnest, and longing to change the world.” He believed that “if the classes could become friends with each other the gulf [between them] would not exist,” Both were trying to escape the social classes into which they had been born.

When Rose and Graham’s engagement was announced it was a sensation, and “for the next two decades, few months would pass when [they] did not appear in the newspapers.” After their wedding in July 1905 they honeymooned in Europe, then settled in the Lower East Side – in a spacious apartment. Graham supported Rose’s mother and younger siblings. As the star of a Cinderella story Rose was much in demand as a journalist and as the subject of articles. She began a life of interviews, writing, settlement house work and socializing with her in-laws and their society friends.

The two married at a time of labour unrest. In the United States, the richest 1% of the population owned around 35% of the nation’s wealth. In 1905, the IWW (International Workers of the World), a union open to all workers irregardless of skills, race or gender, was founded in Chicago. The Socialist Party of American, founded in 1901, was growing fast, and in 1906 Rose and Graham joined it. Traditional charity, in their view, was a bandage on, and a blinder to, the true plight of workers. Radical transformation of society was needed.

Graham resigned from many charities, but continued running the family company. Though there was a huge incongruity in the Stokes’ public speaking in support of socialism and their privileged private life, they believed they were working for positive change. Graham hosted an elite conference on socialism with twenty pedigreed delegates at the family mansion in Noroton, CT, and in 1908 ran as a Socialist candidate for the New York legislature. They acquired a private island in Long Island Sound, where they hosted well-known leftists, including Mother Jones, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Maxim Gorky, Jack London, Upton Sinclair, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and W.E.B. DuBois. Around 1912 they also acquired a town house in Greenwich Village, a“bohemian paradise” of radial new ideas and projects, such as Max Eastman’s magazine, The Masses, for which John Reed wrote. Hochschild evokes this milieu well.

He also vividly describes the IWW led strike of New York hotel employees, including those at the Ansonia Hotel owned by Graham’s uncle. Following the horrific Triangle Shirt Factory fire (1911) that took the lives of many young women workers, there was a large-scale strike of garment workers in 1913. In one of her speeches supporting their cause, Rose told a rally that she understood their struggles from her own lived experience, and that although she wasn’t a worker now, she would be one day when “all the wealth belongs to the men and women who created it.” Her return to the working class happened sooner than she expected.

By the teens of the century, Rose’s and Graham’s paths were diverging. After his father’s death in 1913 he was in charge of the family business and no longer appeared on public platforms with Rose. Meanwhile, she took up the cause of birth control. In 1916, when Emma Goldman was sentenced to jail for distributing information about contraception, in violation of the Comstock Act, Rose announced to a crowd of supporters in Carnegie Hall that she was going to break the law then and there, and started distributing leaflets to the audience. Naturally she made the news, and her in-laws were not amused.

When World War I broke out, Graham, a former Cavalry officer in the Spanish American War, focussed on “preparedness” for war, and supported the neutral U.S.’s trade with Britain and France. Hochschild points out that “By war’s end, Britain would be spending half its military budget in the U.S. with J.P. Morgan acting as London’s agent and collecting 1% commission on every purchase.” Soon Morgan was acting in the same capacity for France.

When America declared war on Germany in April 1917, the Socialist Party split, with one segment supporting President Wilson’s war “to make the world safe for democracy.” Others, such as John Reed and Eugene Debs, opposed the war, convinced that the U.S. had entered the conflict for fear that American capitalists’ investment in Britain and France would be lost if Germany won. Entering the war just after the first Russian revolution in 1917, the U.S. began a crackdown on workers’ and left wing organizations, a crusade Hochschild describes in vivid detail.

When Rose was arrested on suspicion of violating the Espionage Act, Graham bailed her out, but made it clear to the press that their views on the war differed. This was a turning point in their relationship, and although they did not divorce until 1925, they went their separate ways: Rose to visit the Soviet Union in 1922, and to run as a Communist candidate for Congress. Six months after their divorce, Graham married the daughter of a railroad executive with ancestry tracing back to colonial America. He died in 1960. Rose died young, in 1933, and in poverty except for the kindness of friends.

After the divorce, Rose was no longer active on the left. “It was almost as if [Graham] had been, in a way he never intended, her muse,” writes Hochschild. Also, Americans were more interested in peace and consumer goods than in politics during the 1920s.

Rose wrote that “Love is always justified, even when short-lived, even when mistaken, because during its existence it enlarges and enobles the natures of the men and women experiencing the love.” For a few years, writes Hochschild, the love she shared with Graham made them both “far more memorable than either would have been alone. Indeed, if Rose had been one of the millions of anonymous unsung people who worked at the grassroots for progressive change, she would not be a striking subject for a book. She and Graham, however, were not the only leftist couple who married across class lines at that time, and their romance can be seen as a failed experiment. While Rose’s story grabs reader attention, Hochschild’s book is compelling because he tells a bigger story. He shows us the gap between rich and poor during the Gilded Age and the early 20th century and educates readers in a lucid and accessible sty le about early struggles for a fairer, kinder society.

About the reviewer: Ruth Latta writes about the Manitoba women’s suffrage movement and the Great War years in Canada in her novel, Votes, Love and War (Ottawa, Baico, 2017, info@baico.ca)