Reviewed by Mari Carlson

Reviewed by Mari Carlson

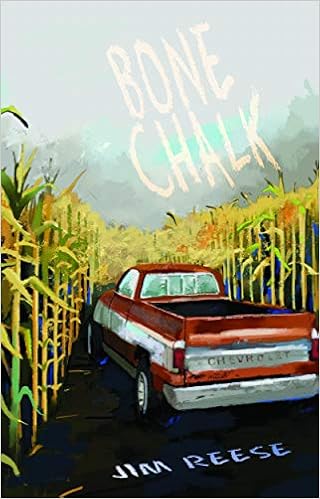

Bone Chalk

by Jim Reese

Stephen F. Austin State University Press

Jan 2020, ISBN 9781622882038, $22.00

Jim Reese’s collection of essays and true stories, Bone Chalk, showcases Middle West small town life with grace, gravity and humor.

Reese grows up in Omaha, attends Wayne State College, Nebraska, where he meets his wife. They move to the countryside where her family lives. Before becoming an English professor in South Dakota, his jobs include Wayne State mascot, farmhand, newspaper reporter (and bundler), and teacher at prisons and jails. He and his wife have two daughters. He is a published author of poetry, stories and essays.

The first story takes place at a diner, the narrator watching himself (“you”) try to fit in among locals. In the succeeding stories, “you” becomes “I.” Instead of looking in from the outside, over the course of the reflections, Reese slowly finds his place among matriarchs and patriarchs in so-called flyover country. His mother and father-in-law each get a chapter, as well as his grandfather. Unlike newspaper reporting, where he “learned whose voice to capture – nobody’s” (90), he captures his elders’ personalities with punchy dialogue and their own tall tales. A favorite of his father-in-law’s is when he and his young buddies help a drunk escape from town jail so they can get a ride home. The day Reese announces that his wife is pregnant for the first time, he discovers his grandfather’s memory is failing. His mother-in-law is characterized by a handwritten sign taped to her door: “Please Ring Twice of Knock or Yell!” (25). Reese’s admiration shows in his close attention to detail.

Reese studies criminals as well as his family members. He goes to high school with a murderer and the girl who becomes his victim. Around the same time, a serial killer also stalks boys in Reese’s neighborhood. These experiences lead him to study Criminal Justice in college and go on to work in prisons. He continually wonders: “Is there a killer inside me?” How removed is any of us from criminality? The chapters on his prison students and these murders raise provocative political and ethical questions.

Other chapters are more humorous. Three are devoted to funny bumper stickers he encounters in his area. In one chapter, “hell bent on gaining new experiences” (112), Reese is the butt of the joke as he drives his boss’s tractor into the garage. He finds his own voice learning how not to imitate clowns he hangs out with in high school and he encourages his daughters and students to find their own voices, too.

Whether serious or silly, Reese’s prose reads like poetry. He says more in a paragraph than most authors achieve over several pages. The final chapters are the shortest and most personal vignettes featuring his wife, daughters and co-workers. Reese finds the profound in everyday, parochial life in Bone Chalk.

About the reviewer: Mari Carlson is a violinist and writer living in Eau Claire, WI. When not reading and reviewing, she is likely teaching or practicing violin. She is an active member of area chamber orchestras and folk ensembles.