Reviewed by Josh Drake

Reviewed by Josh Drake

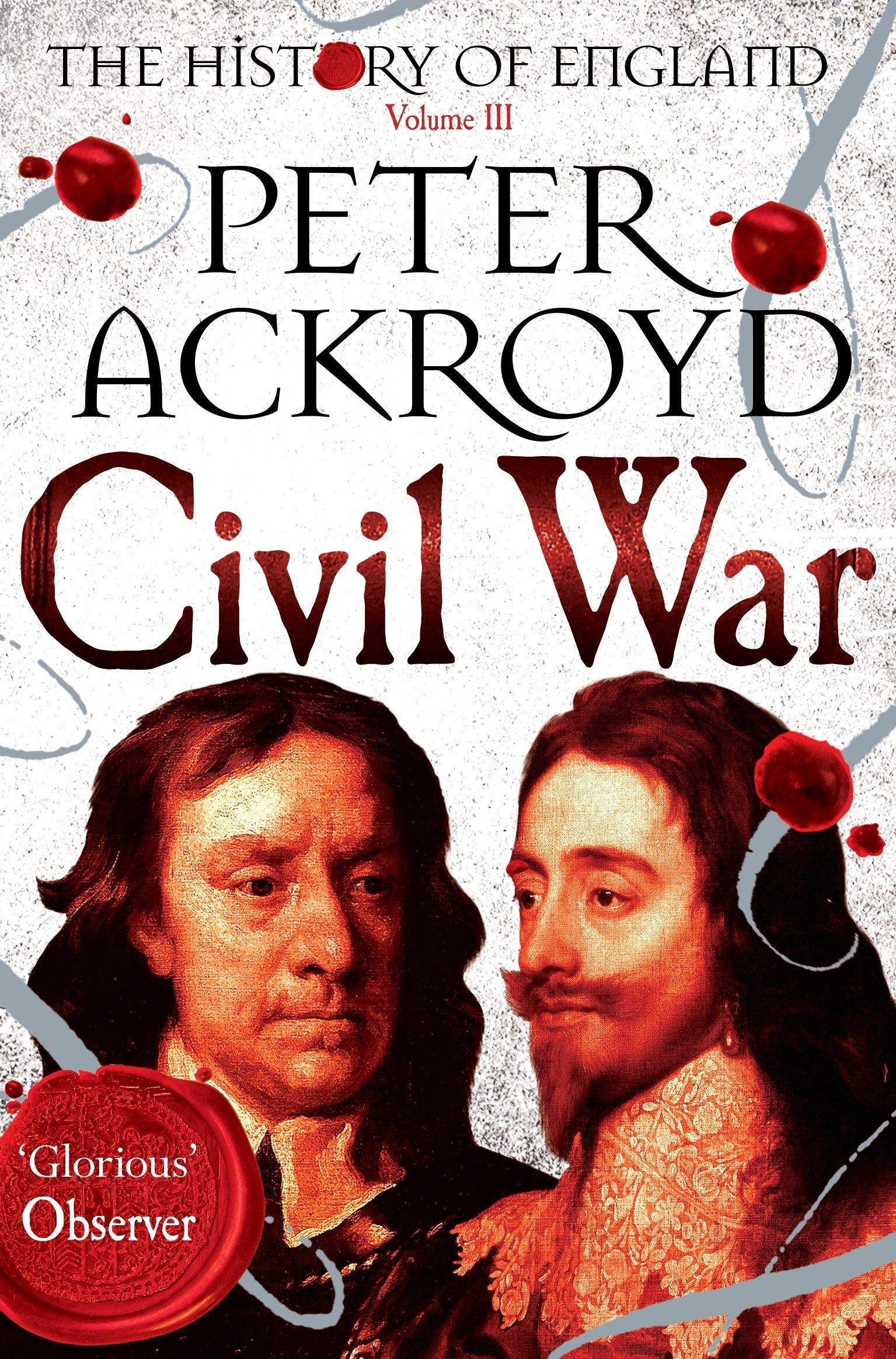

The History of England Volume III: Civil War

by Peter Ackroyd

Pan; Main Market edition

Paperback: 512 pages, ISBN-13: 978-1447271697, 7 May 2015

Civil War is the third book in Peter Ackroyd’s series on the history of England and spans the tumultuous 17th century, from the accession of James I to the English throne in 1603, through the civil wars and Cromwell’s military dictatorship, ending with the overthrow of James II in the ‘Glorious’ revolution of 1689. The book begins energetically with the furious gallop of a courtier bringing news of Elizabeth I’s death to James the VI of Scotland at Holyrood Palace. He assumed the crown of England and became James I, for the first time uniting under one crown England and Scotland. Each subsequent chapter is a vignette detailing an aspect of life during the Stuart period – most chapters follow the main historical arc, but many pause to spotlight various cultural, religious, and political movements. The book puts into context the literature of the day, such as Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan, John Bunyan’s Pilgrims Progress, and John Milton’s Paradise Lost. It also explores broader movements of scientific and religious ideas.

Ackroyd weaves an historical narrative rich in its biographical and cultural details, but sparse in its analysis of cause and effect. He gives the reader a lean account of the main events without judgement; although he will allow himself an occasional economical sentence to summarise the temper of the age: ‘This was an age of religious polemic’; ‘It was an age of music’; ‘It was in certain respects a time of silence.’ This makes it a good book for an introduction into the period for the uninitiated, like me. Ackroyd also manages to capture the lives of ordinary people, whose existence in turbulent times was ruled by fear and uncertainty. When writing about the Jacobean period, this is brought to life by a discussion of Robert Burton’s book The Anatomy of Melancholia, a fascinating and idiosyncratic treatise on the ubiquitous malady of the time. Much of the history is characterised by religious and political schism. While Ackroyd touches on this religious frisson, in my view he fails to truly capture the sense of religious fervour of the time. It was the driving force behind much of the upheaval because of the simple fact that it was still a hugely important aspect of peoples lives. Even Isaac Newton, the supreme experimental genius and mathematician of the age, was called by John Maynard Keynes the ‘last of the magicians’. He frittered away countless hours on what could have been productive endeavours on studies of alchemy and biblical chronology. The 17th century was still a time when religious ideas ardently animated people – evinced by the explosion in religious sects, from anabaptists and quakers, to fifth monarchists and muggletonians.

Oliver Cromwell, the key focus of the book, was zealous in his religiosity; he believed he was fulfilling divine destiny, which gave him extraordinary focus and drive when he believed he was backed by providence: ‘This extraordinary man, without any other reason than because he had a mind to it…mounted himself into the throne of three kingdoms, without the name of king, but with a greater power and authority than had ever been exercised or claimed by any king’. He had a mind to it because he believed he was doing God’s will. Because of his drive and military prowess he ascended through the ranks of the army to become one of the principal commanders of the New Model Army during the civil war period 1642-49. He then infamously lead the brutal campaign into Ireland to stamp out royalist opposition. Victories in war and success in parliament placed him in a position of first among equals, styled ‘Lord Protector’, during England’s flirtation with republicanism. He remains an intensely controversial figure; at times he could be fun-loving and playful:

“At the end of the discussion Cromwell, in one of those fits of boisterousness or hysteria that punctuated his career, threw a cushion at one of the protagonists, Edmund Ludlow, before running downstairs; Ludlow pursued him, and in turn pummelled him with a cushion.”

Cromwell could also be unsure of himself and had routine periods of soul searching and vacillation, but he was far stronger willed and more decisive than any of the kings of the period.

Ackroyd describes James I as extravagant in his personal tastes, as well as learned and eloquent on state matters, but with a tendency to prevaricate over important diplomatic or military decisions. He had been king of Scotland since the age of 13 months, and had acquired a belief in the divine right of kings and consistently butted heads with Parliament over his understanding of English Common Law. For example, on his way down to London he executed a common criminal without due deference to the procedures of the law. A lifetime of political intrigue and violence had made James shifty and paranoid. He was the king that famously survived attempted assassination in the ‘gunpowder plot’. His overriding goal was to unite the kingdoms of Scotland and England under a unified religion and parliament. However, he was unpopular with parliament because of his intended alliance with Spain and he constantly had to petition for funds. When money was not forthcoming, he resorted to alternative means of income by creating and selling dignities. Perhaps his greatest legacy was a new authorised English translation of the Bible.

Charles I inherited his father’s belief in the divine right of kings. Although his hand was forced in several circumstances during the civil war and he was required to make concessions, he would never wholly concede and always tried to strengthen his position through underhand deals and connivance. Ackroyd recounts the colourful episode when, as a young prince, he set out on an ill-fated adventure to claim the Spanish Infanta as a bride. He was held hostage, but during this time he developed an exquisite taste in European art, and when released brought much of it back to England, such as Andrea Mantegna’s Triumphs of Caesar. Charles, like his father, had quarrels with parliament about money. His solution was to abandon parliament for a period of eleven years and impose a personal rule. To remain solvent, he resorted to extrajudicial sources of revenue such as the highly controversial ship money levy. His main character fault, it seems, was an inability to empathise with others and understand other people’s viewpoints, so he maintained a unbending view of kingship. Ackroyd writes, “He could never see the point of view of anyone but himself, and this lack of imagination would one day cost him the throne.” Although it must be said that during the trial leading up to his execution, Charles remained admirably calm and steady.

Charles II, who was restored to the throne following the death of Cromwell and the disintegration of the protectorate, was known as the ‘merry monarch’. Famous primarily for his innumerable mistresses, he is also portrayed as devious and secretive. His jovial epithet, however, belies the general malaise of this period. Ackroyd captures a sense of mounting gloom and rampant speculation on the end of days that gripped ordinary people. To many, the apocalypse was presaged by the plague and the subsequent great fire of London in 1666. Prognostications of doom indeed. London, five sixths of which was destroyed, bounced back quickly with room for more permanent architecture such as Christopher Wren’s ambitious new St. Pauls cathedral. For these scenes, Ackroyd relies heavily on the animated diary writing of Samuel Pepys.

Civil War is not for those who want a detailed account of the Civil war period specifically; it is particularly void of military detail, but offers an insightful and vivid narrative of the whole of 17th century England that retains the period’s intricacy and complexity. While Ackroyd’s style is to make the civil war period seem rather like a series of accidents, common themes emerge that still influence our culture today. Most notable was the refinement of the role of parliament in a constitutional monarchy and an emphasis on the due process of the law. It’s easy to view 17th century England as a time of intense religious and sectarian violence, but one can also sense the development of religious toleration and burgeoning belief in science, experimentation, and reason. The century also witnessed the last successful invasion of England by the Protestant William and Mary, who became the new monarchs after usurping James II, a staunch Catholic.

About the reviewer: Josh Drake Edinburgh University biology graduate from South Africa. He reviews books on history and popular science. Find out more about Josh at: https://joshuadrakeblog.wordpress.com