This selection of short stories concluding with the major work “Datsunland” is beautifully written by a literary craftsman. They take the reader through and within the landscape of South Australia’s unique ecosystem, into places tinged and contaminated with saturnine and fateful conclusions. As I searched through the pages I found myself trapped within a boiled down distillation of this state’s home-style miseries and heartbreaks.

This selection of short stories concluding with the major work “Datsunland” is beautifully written by a literary craftsman. They take the reader through and within the landscape of South Australia’s unique ecosystem, into places tinged and contaminated with saturnine and fateful conclusions. As I searched through the pages I found myself trapped within a boiled down distillation of this state’s home-style miseries and heartbreaks.

Category: Literary Fiction Reviews

Veracity and Transformation: A Review of Grief Cottage by Gail Godwin

The book is wonderfully informed by multiple metaphorical depictions of our inner and outer struggles. Young Marcus loses his mother, his only parent, and goes to live with his eccentric and spiritually bruised great Aunt Charlotte on a small island in South Carolina at the beginning of the summer. Aunt Charlotte has past wounds that haunt her, rendering her a reclusive but renowned local painter.

The book is wonderfully informed by multiple metaphorical depictions of our inner and outer struggles. Young Marcus loses his mother, his only parent, and goes to live with his eccentric and spiritually bruised great Aunt Charlotte on a small island in South Carolina at the beginning of the summer. Aunt Charlotte has past wounds that haunt her, rendering her a reclusive but renowned local painter.

A review of An Accidental Profession by Daniel S. Jones

Undoubtedly, it’s rather nice to think that others are toiling away while we read about them, and the similarities and differences with our own working lives emerge with unusual clarity: occupations do not have to be exotic or abstruse for us to find them fascinating. An Accidental Profession is all about work: its organization and administration, what it does to people, the power of the corporation, our ambivalent relationships with our co-workers.

Undoubtedly, it’s rather nice to think that others are toiling away while we read about them, and the similarities and differences with our own working lives emerge with unusual clarity: occupations do not have to be exotic or abstruse for us to find them fascinating. An Accidental Profession is all about work: its organization and administration, what it does to people, the power of the corporation, our ambivalent relationships with our co-workers.

Interview with Melinda Smith

The award-winning author of Goodbye, Cruel, reads from her new book and talks about how it came together, the structure, her linked suites, the influence of Dante, her attraction to Rabi’a Balkhi and Persian poetry in general, on writing about sensitive…

A review of She Receives the Night by Robert Earle

As described by the publisher, that is an ambitious undertaking for any writer – especially perhaps for a male writer – and one that requires immense artistry and intelligence. Earle has these things in abundance, and he uses them to compelling effect. Many of these stories are gems of the form; they feel inevitable, surprising, effortless.

As described by the publisher, that is an ambitious undertaking for any writer – especially perhaps for a male writer – and one that requires immense artistry and intelligence. Earle has these things in abundance, and he uses them to compelling effect. Many of these stories are gems of the form; they feel inevitable, surprising, effortless.

A review of Waiting by Philip Salom

This is the human condition: oddly shapen, oddly matched, solitary, inter-dependent, vulnerable, and always waiting for something to change. It’s repulsive and loveable all at once. Waiting is critically important – a novel that tells little and shows much, leaving its readers full of fresh insight.

This is the human condition: oddly shapen, oddly matched, solitary, inter-dependent, vulnerable, and always waiting for something to change. It’s repulsive and loveable all at once. Waiting is critically important – a novel that tells little and shows much, leaving its readers full of fresh insight.

A review of Peregrine Island by Diane B. Saxton

Weather plays a profound role in the novel; it is almost a character. Fog, dark clouds and storms set a mood, suggesting that the Peregrines are subject to forces beyond their control. Young Peda, the family member most in tune with nature, has a strong need for friendship and a belief in magic that lead to a positive outcome for her family members.

Weather plays a profound role in the novel; it is almost a character. Fog, dark clouds and storms set a mood, suggesting that the Peregrines are subject to forces beyond their control. Young Peda, the family member most in tune with nature, has a strong need for friendship and a belief in magic that lead to a positive outcome for her family members.

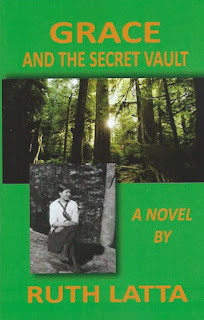

A review of Grace and the Secret Vault by Ruth Latta

Latta tells this story in a fluid, fast-paced and conversational way, seamlessly weaving together the daily details of life in the British Columbia of a century ago with the book’s overarching political narrative. The characters’ dialogue is conveyed convincingly in the lexicon of the day, but the emotional pull of the story is timeless. And despite its subject matter, the author avoids propagandizing.

Latta tells this story in a fluid, fast-paced and conversational way, seamlessly weaving together the daily details of life in the British Columbia of a century ago with the book’s overarching political narrative. The characters’ dialogue is conveyed convincingly in the lexicon of the day, but the emotional pull of the story is timeless. And despite its subject matter, the author avoids propagandizing.

A review of Something You Once Told Me by Barry Stewart Hunter

Trains and boats and planes – modes of transport abound in Barry Stewart Hunter’s interestingly varied collection of short stories, although the people they convey are seldom up to speed with their own lives. Persons in transit and the mental dislocations they experience are a recurring motif; thematically, however, there is a great deal more going on, much of which is intriguingly elusive.

Trains and boats and planes – modes of transport abound in Barry Stewart Hunter’s interestingly varied collection of short stories, although the people they convey are seldom up to speed with their own lives. Persons in transit and the mental dislocations they experience are a recurring motif; thematically, however, there is a great deal more going on, much of which is intriguingly elusive.

A review of Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

Anna Karenina is a novel that beguiles and intrigues. The world it depicts and dissects remains fascinating in itself. Its characters are among the most memorable ever created. And the targets and outward forms of social disapproval may be different now to what they were then, but they nevertheless exist. The world is still an awfully harsh place to those who step out of line or who cannot enter into prescribed ways of thinking and feeling.

Anna Karenina is a novel that beguiles and intrigues. The world it depicts and dissects remains fascinating in itself. Its characters are among the most memorable ever created. And the targets and outward forms of social disapproval may be different now to what they were then, but they nevertheless exist. The world is still an awfully harsh place to those who step out of line or who cannot enter into prescribed ways of thinking and feeling.