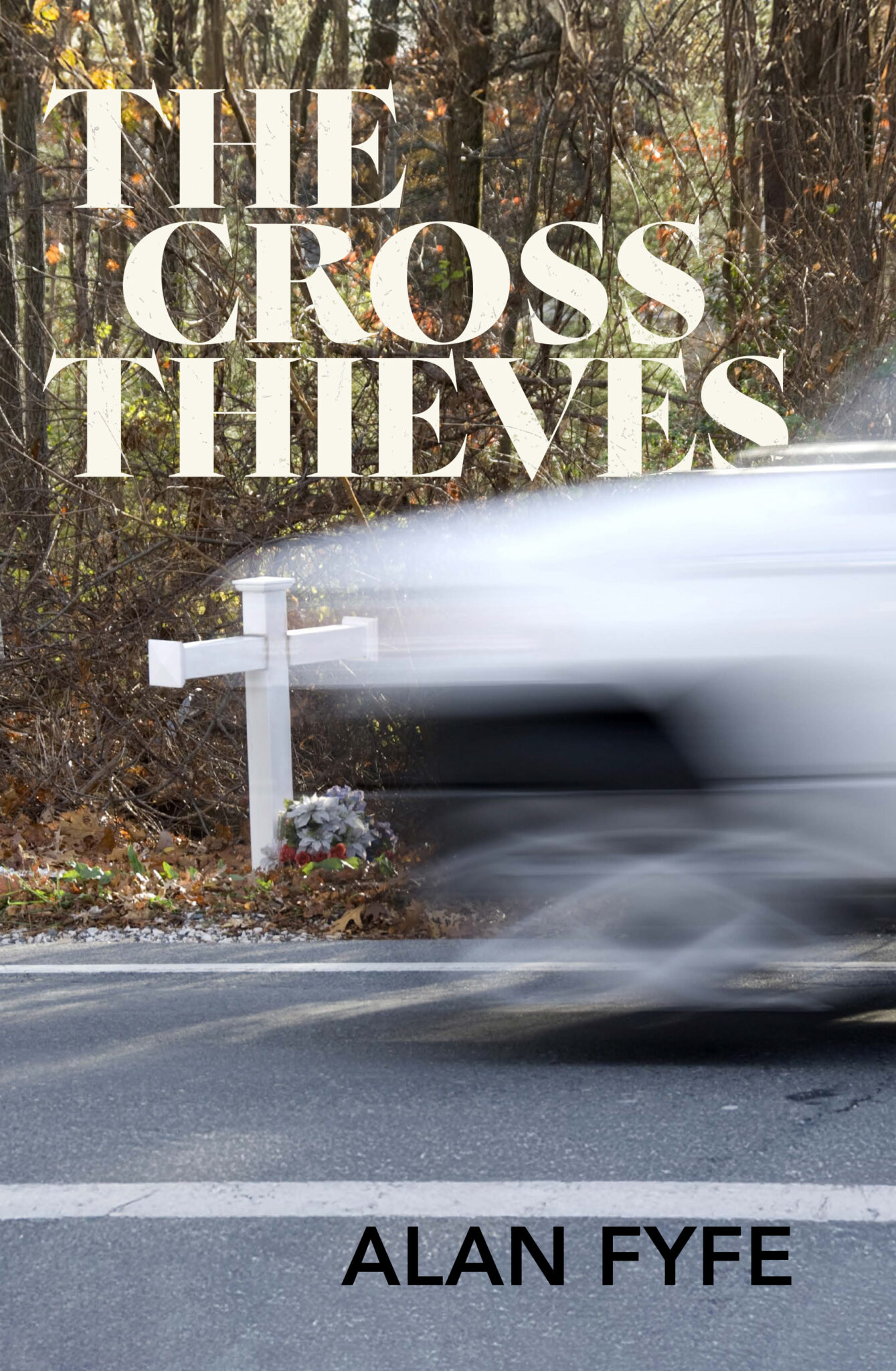

The book is full of beautiful, funny, often tragic contradictions that are so well woven into the fast-paced plot that at times you have to force yourself to slow down to appreciate them. The Cross Thieves is a terrific book, full of gritty violence and desperate characters, but also infused with a tenderness that borders on transformative.

The book is full of beautiful, funny, often tragic contradictions that are so well woven into the fast-paced plot that at times you have to force yourself to slow down to appreciate them. The Cross Thieves is a terrific book, full of gritty violence and desperate characters, but also infused with a tenderness that borders on transformative.

Category: Literary Fiction Reviews

A review of Prairie Ashes by Ben Nadler

Prairie Ashes is well worth your time. Whatever your interests, it is the duty of the working class as much as it is the rentier class to understand what was once possible in the pursuit of a more equal society. Orwell found it once in Spain; even if for a brief time, it proves that things must not always be as they are, as well that authority is not invincible or necessary in its unjustified form.

Prairie Ashes is well worth your time. Whatever your interests, it is the duty of the working class as much as it is the rentier class to understand what was once possible in the pursuit of a more equal society. Orwell found it once in Spain; even if for a brief time, it proves that things must not always be as they are, as well that authority is not invincible or necessary in its unjustified form.

New giveaway!

We have a copy of Slipstream by Kristyn Saunders to give away!

We have a copy of Slipstream by Kristyn Saunders to give away!

To win, sign up for our Free Newsletter on the right-hand side of the site and enter via the newsletter. Winner will be chosen by the end of February from subscribers who enter via the newsletter. Good luck!

A review of A Place in the World by Bill Gaythwaite

Gaythwaite’s sheer wittiness is a delight, even without the gripping moral dilemmas that propel the stories forward and the vivid, often morally questionable but nevertheless endearing characters who bring the plots alive. The reader turns the pages to see how their situations are resolved – or not resolved.

Gaythwaite’s sheer wittiness is a delight, even without the gripping moral dilemmas that propel the stories forward and the vivid, often morally questionable but nevertheless endearing characters who bring the plots alive. The reader turns the pages to see how their situations are resolved – or not resolved.

A review of Your Place in This World by Jake La Botz

Jake La Botz writes with a bruised, musical lyricism, capturing revelations that arrive not through grand redemption but through small, fleeting graces. His stories linger in the aftermath of failure, curious about what it means to find beauty, dignity, and purpose amid addiction, poverty, and social abandonment in Chicago’s forgotten neighborhoods. La Botz does not romanticize poverty or misfortune; instead, he demands on showcasing his characters’ humanity.

Jake La Botz writes with a bruised, musical lyricism, capturing revelations that arrive not through grand redemption but through small, fleeting graces. His stories linger in the aftermath of failure, curious about what it means to find beauty, dignity, and purpose amid addiction, poverty, and social abandonment in Chicago’s forgotten neighborhoods. La Botz does not romanticize poverty or misfortune; instead, he demands on showcasing his characters’ humanity.

A review of We Had it Coming and other fictions by Luke O’Neil

There’s a strong sense of place throughout the collection, but with the shading of resigned desperation, almost as keen as describing a memory while it is still being formed. O’Neil often points to the small tortures of acknowledging the sharpness of reality alongside and our shared passivity: “Being lied to isn’t so bad sometimes compared to being aware of how things actually are. You wouldn’t want to go around like that for very long. No one wants to know all the secrets.”

There’s a strong sense of place throughout the collection, but with the shading of resigned desperation, almost as keen as describing a memory while it is still being formed. O’Neil often points to the small tortures of acknowledging the sharpness of reality alongside and our shared passivity: “Being lied to isn’t so bad sometimes compared to being aware of how things actually are. You wouldn’t want to go around like that for very long. No one wants to know all the secrets.”

New giveaway!

We have a copy of The Woman in the Ship by Sapphira Olson to give away!

We have a copy of The Woman in the Ship by Sapphira Olson to give away!

To win, sign up for our Free Newsletter on the right-hand side of the site and enter via the newsletter. Winner will be chosen by the end of January from subscribers who enter via the newsletter. Good luck!

New giveaway!

We have a copy of Behind These Four Walls by Yasmin Angoe to give away!

We have a copy of Behind These Four Walls by Yasmin Angoe to give away!

To win, sign up for our Free Newsletter on the right-hand side of the site and enter via the newsletter. Winner will be chosen by the end of January from subscribers who enter via the newsletter. Good luck!

A review of The Old Man by the Sea by Domenico Starnone

If identity is to be found in reviewing “key moments” in life and not be trapped by “sentimental life . . . so full of hiding places,” then Starnone’s novel must be read like a detective novel that travels in time and space, all from the comfort of a beach chair in which an old man sits by the sea, waiting to catch the fish of a lifetime, gold and shimmering, one filled with promise and food for a tired soul.

If identity is to be found in reviewing “key moments” in life and not be trapped by “sentimental life . . . so full of hiding places,” then Starnone’s novel must be read like a detective novel that travels in time and space, all from the comfort of a beach chair in which an old man sits by the sea, waiting to catch the fish of a lifetime, gold and shimmering, one filled with promise and food for a tired soul.

A review of Fit Into Me by Molly Gaudry

So many of Gaudry’s sentences, from the very first – “Because most nights during the final semester of my MFA at George Mason University, while recovering from a mild traumatic brain injury, I fell asleep watching Prison Break on my laptop in bed.” – to the penultimate sentence – “Because words, imagined in the greatest yearning, as a means of finding love, defining it; as a means of shaping it (This is how it feels, this is where it hurts) and sharing with others its permutations, astonishments, exaltations, and erosions.” – seem to offer an explanation for some unstated condition.

So many of Gaudry’s sentences, from the very first – “Because most nights during the final semester of my MFA at George Mason University, while recovering from a mild traumatic brain injury, I fell asleep watching Prison Break on my laptop in bed.” – to the penultimate sentence – “Because words, imagined in the greatest yearning, as a means of finding love, defining it; as a means of shaping it (This is how it feels, this is where it hurts) and sharing with others its permutations, astonishments, exaltations, and erosions.” – seem to offer an explanation for some unstated condition.