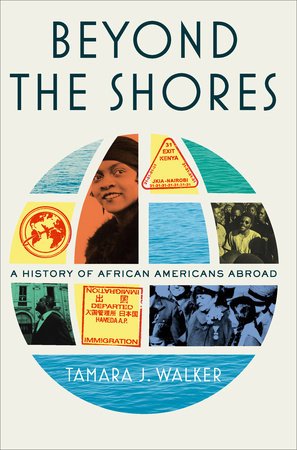

Beyond the Shores

A History of African Americans Abroad

by Tamara J Walker

Crown

Hardcover, $28.00, Jun 2023, 352 Pages, ISBN 9780593139059

Has the American dream come at the expense of the black American? This question was debated at the Cambridge union between writer James Baldwin and conservative pundit William F. Buckley Jr in 1965. Mind, this was an audience of collegiate English people, which meant it was nearly all white and nearly all male. That, so to speak, was the price of admission for Baldwin to speak on this question at all in not quite post-colonial England. One must wonder what Buckley’s thoughts were as he considered his arguments against the motion. Had he asked himself if he was even qualified to speak on such a subject? To say that America was fair to blacks?

Indeed, Baldwin had an easy answer at hand: all of the vaunted structures of American society, its economy, its standards of living, these could not be what they are if there had not been and did not still continue to be a history of, as Baldwin put it, “cheap black labor”. Beneath that phrase lies a Sisyphean boulder of misery and injustice that every black and bipoc person in America must shoulder in their own way. What to think of your home country from behind that boulder, far down the hill of the vaunted American dream?

Beyond the Shores considers what comes after. It is a collection of stories of black expatriates from a myriad backgrounds who thought to find a new home abroad. If not a home, then at least a nice place to stay and catch their breath.

It is here that I ought to make an autobiographical aside. I am not black. I have not been deeply in community with black people, only shallowly and recently. I have been fortunate to have a wonderful partner who happens to be bipoc, and to have had a chance to talk with her family. When I speak of black people here, I speak of the entire black American experience: blacks and every kind of multiracial blacks. Colorism has no place in Walker’s work and won’t here. I will speak in very strongly worded terms upon a subject I believe requires that seriousness. But I do not speak for black people. I come to this, I know, as a tourist. I hope to be one who listens well.

I recently had dinner with my partner and her parents and half brother, one of whom has traveled the globe as a musician, another who has become a permanent resident of France, and a third who came late to America from Puerto Rico. And we are very lucky to have her.

The first element of high praise that I will give Beyond the Shores is how closely it registers their experiences. In my partner’s family’s words there are echoes of this book’s stories, at times almost word for word. It needs little saying that this is a well sourced collection, thoughtfully assembled to weave as many of the myriad threads as its fingers can catch into a continuous narrative. Tamara J. Walker deserves recognition for how adroitly she has composed this book. This is not to mention how well she tells the stories. It is as though she knew her subjects personally. Her prose meets Orwell’s standard: being clear as a pane of glass. It is a window into the past and recent future, and one with very few streaks across its surface.

Wherever you go, there you are. A truism about the inevitable self we find wherever we may go. Much more pressing here, though, is what those who occupy your destination think of the self that you’ve brought with you. A constant both here and in my conversations is that, though largely these black people experienced less racism abroad themselves, they would find that it was often because being American was more important than being black. So it is that the Senegalese are much less welcome in Paris than was Baldwin. The mind of the racist is centered upon the idea of the manufactured other. It so happens that an American, however black, is less the other than is a person who comes from a current or previous colonial possession. Racism is bred and not born. Each society vomits it forth in its own peculiar way. So many of those whose stories are here recounted find themselves on an uncomfortable fault line of identity. What does it mean to see in the Afro-French a mirror of their experiences back in America? And yet, in this eerie twilight, the African American (a term which closes off far too much of the black experience) finds themselves an observer in the victimization of another. And does not observing always feel a form of complicity?

One thought stuck with me from that dinner: the French expat said, “you’re only home when you don’t have a set date to leave”. So often in this book are those who have to try to straddle that line. Should you bring your family to the Soviet Union, where you saw a barber throw out two racist Americans for urging him to deny you service? So it was for Joseph J. Roane and Oliver Golden. How hard will it be for your family to adjust to, not to mention cope with, leaving their family and community? What does it mean for there to have been black bolsheviks like Cyril Briggs around 1919? This, just after the abortive 1918 attempt by America to interfere in the aftermath of the October Revolution. What made Roane and Golden feel welcomed and even elevated at that time? Not that those positive experiences could entirely protect their colleague and engineer Robert Robinson from “enough punches and kicks to send him to the hospital”. Was revolutionary Russia plagued still by Tsarist racism? Not in this case: it was his white American coworkers who had “taken their racial hatred along with them in this new land, as though it were an essential piece of luggage”. Like it or not, America has its hooks in you. You’re a part of it. And it’s a part of you. That separation can never be anything but painful.

Another thought: “I never felt American until I bought a house”. This was echoed by “how can you call someplace home if you don’t own a piece of land?”. It’s hard to even consider what it might take to own land and a home when you can’t even decide where you live. Even in France, performer Florence Mills found herself redlined out of finding a place to stay outside of Goat Alley, a fact so common as to inspire a piece about it, Goat Alley by Ernest Howard Culbertson. Even so, that piece disparaged black residents: it portrayed them as “[drinking] too much, [fighting] endlessly…and were always the source of their own troubles”. Nearly all black by the early 1900s, Goat Alley was a place of “mercenary landlords” that was “unfit for human habitation”. It was a neighborhood with one way in and one way out, carved into the city to contain an unwelcome population. Consider: for all that Harlem is associated with black people as far back as the Harlem Renaissance and the struggles that led up to it, that at one point blacks were redlined out of it almost entirely. Such is the arc of white habitus, describing in its parabola the movements of those it subjugates. New York City never sleeps. And when it’s awake, there’s a constant shift of gentrification. Projects there to follow in the neighborhoods that are no longer favored by the bougie. And that’s where the old residents of the gentrified neighborhood might end up when they’re priced out of their homes. So the free market dictates.

This calls to mind another thing the expat said. “Why fight for a country where you can’t own land?” When asked, he said he wouldn’t fight for France, either. And why should he? This collection is replete with stories of black soldiers who found suspicious glances abroad and Jim Crow at home.

“Is the kind of America I know worth defending? Will America be a true and pure democracy after this war? Let colored Americans adopt the double VV for a double victory. The first V for victory over our enemies without, the second V for victory over our enemies within.”

So muses twenty-six-year-old James G. Thompson. Imagine being in the bloody fields of the second world war and thinking to yourself: I have another fight waiting for me when I get back to America. Why not simply stay on after the war, find a new life? But then, giving up everything you know is hard. And who knows what you’ll find where you stay.

Another strain: “I feel like a spectator here. I saw in the commercials houses and products I could never have when I’m growing up in the projects”. That feeling of being a spectator extended to their time abroad. The expat was seen as an almost white American in French black society, and also seen as white as well in white society. One of the “good ones”. Racism is a morass. You can watch society, but you cannot be of it until you are welcomed. When one of Walker’s stories recounts the life of actor and later screenwriter Kim Bass in Japan, it is a story of constantly being an anomaly in your own home. Your roles are what they are because you’re black. Nobody will let you rent: will you take off your shoes? Will you bother the neighbors? Maybe you’ll get a chance to be treated decently if you speak good Japanese. One population well highlighted by Walker is konketsuji, soldiers’ children who were unclaimed or left behind after the war. They could be “refused admission to nursery school, kept from attending high school or college, and were faced with high unemployment”. Worse still if you happened to be black. Japan does not want you. An American soldier has abandoned you. You can live in a society, maybe even thrive in it. But your blackness will other you in ways you can’t always account for. Home is, too, a place you have to feel part of.

Beyond the Shores is well worth your time and attention. It would be so even if it were not so well written and compiled as it is. These are stories that need to be heard. Stories that the American story is a lie without. For as long as red lining exists, generational wealth is matched by generational poverty, cops murder blacks without consequence, racism is at the workplace and in the streets, and much else: we are not a nation that lives up to its promises. Read of the black experience at home and abroad. Consider a world arrayed against you, one where you can never fully escape the shadow of Jim Crow and the Middle Passage, but also one where respite might come far from home. Ask yourself: has the American dream come at the expense of the black American?

Oh, and before I forget to mention it: Baldwin carried the day with 544 in favor and 166 against. It might mean for such a broad majority to simply nod along and say with perfect lumpen quietude ‘the blacks have it bad’. But one must make another consideration. 166 people in that room looked at the last 400 years of black history in America and thought, hey, they don’t have it so bad.

About the reviewer: Matt Usher is a hopeful writer desperate to escape a miserable day job. They are an agender writer and musician and like poetry, tabletop roleplaying, trading card games (mtg and ygo), and professional wrestling. They are based out of Brooklyn with their two partners in a happy polecule. This is their first publishing credit. Most of their works are short stories but somehow the piece of lit crit got there first. If you want to reach out and/or contact them regarding their stories (please do), you can find them at https://bsky.app/profile/mattusher.bsky.social.”