Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

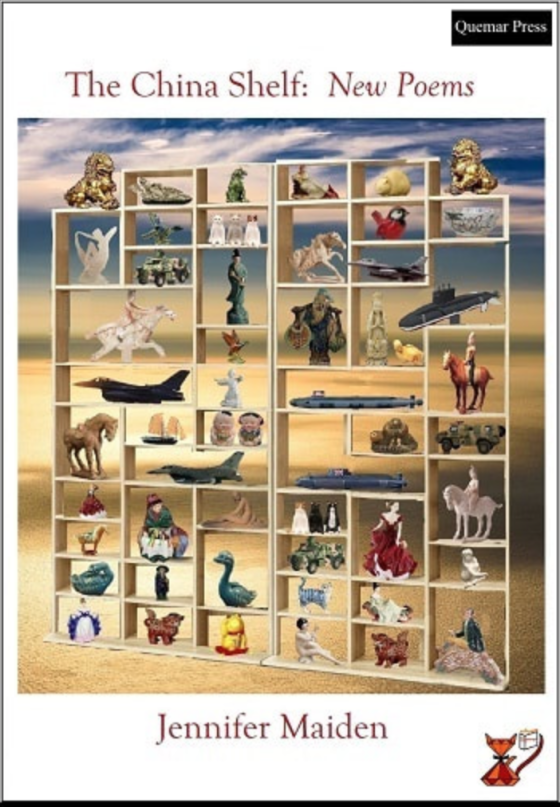

The China Shelf: New Poems

By Jennifer Maiden

Quemar Press

Paperback, $A18.50, 64 pls, ISBN: 978-0-6457126-5-0, Jan 2024

You don’t have to have the kind of encyclopaedic knowledge of Australian history and command of current affairs that Jennifer Maiden does to read her books, but it definitely helps with the many puns, depictions, references, and a wry series of associations that has become characteristic of her work. The China Shelf is certainly no exception. Maiden has created a poetic universe of her own that exists beyond and between books, with characters who reappear like dream apparitions, bringing with them their own fictional histories from previous poetry and fiction books.

With such an extensive oeuvre, Maiden has plenty to draw on. For fans, there is pleasure in re-entering these complex and well-constructed worlds where events of the world collide with the events of Maiden’s fictive universe. There is George Jeffreys, for example, who has been in Maiden’s books since 1990 – probation officer turned international operative and partner of Fratricide and onetime client Clare Collins. There is Brookings, the small, cuddly ’pombat’ who, in some ways, represents the American Brookings Institute, returned from her book Brookings, The Noun.

True to his fashion as wombat and possum

Brookings was for a short time Death Destroyer

of Worlds in a stylish hat like Oppenheimer

after seeing that movie but he never

discovered how to rescue whatever

bit of bush he had flattened after,

so he could sleep on it comfortably again. (“Brookings Becomes a Cardboard Drone”)

There are references to other fiction characters but also real characters who exist in fiction form in Maiden’s work: former Deputy Leader of the Australian Labor Party Tom Uren, Gore Vidal, Julian Assange, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Anthony Albanese to name a few of Maiden’s ‘characters’ who mirror their real life cohorts of literary figures, criminals, and world leaders, while also bringing in a fictive histories to the new work. In the world of The China Shelf, these characters can converse with one another or even become tchotchkes on a metaphorical shelf, able to be toyed with and forced to reckon with what they’ve wrought. It’s an ambitious undertaking and the external references are a constant, but Maiden has been doing this for a long time and the poems feel seamless:

Hiroshima/ Hanoi /Shangri La, Mon Amour in Singapore,

rhymed Tom Uren wearily as he woke as he had before

at an Albanese keynote where mum’s china shelf at war

seemed high pitched, proud and fragile even more.b(“Hiroshima/ Hanoi /Shangri La, Mon Amour in Singapore”)

To get every reference requires a similar kind of mind to Maiden’s, or an awful lot of Googling, particularly for those who didn’t grow up in Australia. However it’s not hard, or unpleasant to do so, and Maiden’s more experienced readers will pick up on the often-used structures in which a historical, generally political figure wakes up in a familiar place and has a conversation with another political figure – generally the second one being a no longer alive mentor of sorts. There are five such poems in The China Shelf as well as several of the “diary poem” style which metapoetically break the fourth wall to muse about the work itself in a way that both uses poetic technique like imagery, metaphor, rhythm and even a hint of off-rhyme with a narration that reads like lineated essay:

Recently when Timor-Leste’s José Ramos-Horta

wrote on Australian anger at his agreement with China,

he described ‘Imagined Chinese ghosts in Australia

mainstream and rightwing media.’ However,

the use of the metaphor is one I’d like consider

as much for its cultural perceptions and power. (“Diary Poem:Uses of Chinese Ghost”)

Another poem about “shelfies” explores the notion of books as objects, but also hints that this whole collection is a shelfie of sorts – not so much for books but for the many items that form the china shelf:

I have a partiality to shelves, of course,

and of course to books as objects,

even if in shelfies books as pets,

but there seem to be strange uses

too of this as Intel Agencies grow

more desperate about the internet. (“Diary Poem: Uses of Shelfies”)

As with all of Maiden’s books, The China Shelf is often funny, partly because of the way she puts characters together – as if they were paratactic lines of poetry, and by association and taken out of time and place, the character is changed:

Tom Uren woke up aghast in San Diego, where Albanese

his frail young friend signed a contract, grinning and uneasy

with rich Sunak, stiff Biden, Victoria Nuland like a smug plump

smile

in plastic on a short shopfront in Davos, front-rowed in approval,

anticipating a new Ukraine better than her last endeavour

and this time tooth-fresh and sparkling in Port Kembla. (“Tom Uren Woke Up Aghast in San Diego”)

There are no notes or glossary, but neither is the book polemical. You are free to make your own conclusions from what comes across essentially, at least to my ignorant mind, as poetic play—full of irreverence and an open sense that we are all pawns in the global power play, and that no matter how powerful these world figures are – whether they be actors, writers, or politicians, it behooves us to pay attention and use our imaginations to engage. Of course in Maiden’s case, it helps that she has a solid command of the poetic pitch developed from years of engaging, paying attention and playing. You may not get every reference in The China Shelf, but you will think, and come away, even from a first reading, smarter.