Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

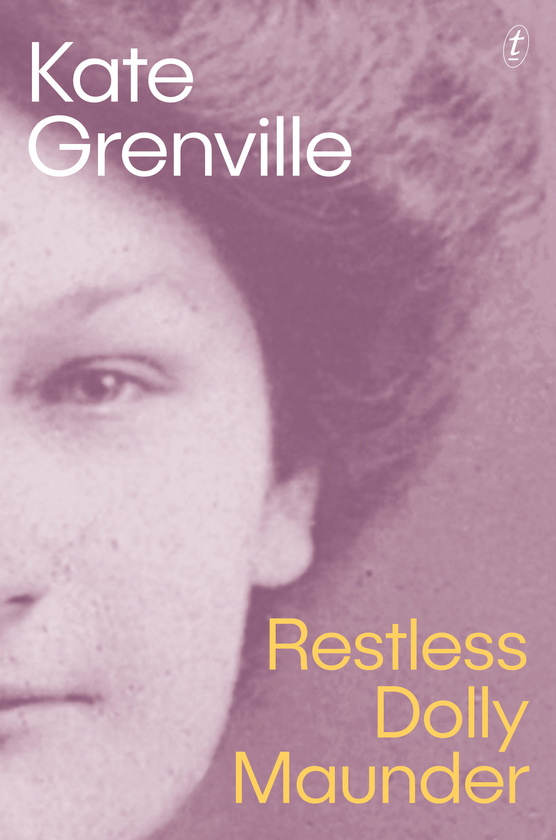

Restless Dolly Maunder

By Kate Grenville

Text Publishing

Hardcover, July 2023, ISBN-13: 978-1922790330, 304 pages

Readers of Kate Grenville’s 2015 memoir One Life: My Mother’s Story will be familiar with Grenville’s mother Nance. Nance is a terrific character who struggles to be a loving, engaged mother while managing an extremely busy career as a pharmacist. Nance’s grouchy restless mother Dolly is also part of One Life, but Dolly is ‘unreliable’, exacting, judgemental, and lacking in warmth in One Life.In Grenville’s new book, Restless Dolly Maunder, Grenville uses her skill as a novelist coupled with the many written accounts her mother left to create a complex and sympathetic portrait of Dolly. The story contextualises the disappointment Dolly carried her whole life, but also shows her tenacity, intellect, and capability, often undermined by the expectations of what it meant to be a woman in 19th century Australia.

Although they can certainly be read individually, both One Life and Restless Dolly Maunder work beautifully as a set, as Grenville makes a clear link between Nance and Dolly, and the lives they lead. Grenville writing is consistently lovely, charged with an energy that seems to mirror Dolly’s own. Dolly’s arc is a strong one, which often becomes poetic during the many transition points that change the story’s trajectory, as in this moment when the weather destroys Dolly and her husband Bert’s farm just before what looked to be their first successful crop:

The morning started fine, but as the afternoon came on something peculiar started to happen on the horizon. A great tangled tube of cloud came towards them, coiling over itself as it moved across the sky, seething against a background of smeared grey. The air was suddenly full of huge wind, leaves and sticks violently hurled up, rattling against the windows. Dolly watched a shrivelled hole int eh cloud opening slyly around a ragged edge of smear, and a line of lightning like a crack in fine china, white and sharp against the dark cloud. And the boiling tube of cloud plaiting itself into itself as it rolled slowly across the sky, so dark a grey it was almost blue, shot with that cold white lightning. (85)

Though Grenville only brings her own perspective in during the final chapters, with the rest of the book labelled fiction, the book is suffused with a tenderness that comes from obvious empathy and understanding. This connection is coupled with research that is evident in the detail of Dolly’s settings, creating a story rich with verisimilitude and immediacy:

The train station was just across the road from the shop and once a week she’d go into the city. Getting out, a chance o scene: that was a luxury she’d never had. Oh, she loved the bustle and rush of town, the feeling o life being lived at a faster pace, the windows full of things you’d never buy but loved to look at, above all the sense that no one knew who you were. (94)

While Dolly’s life may not be what she had hoped as a girl, and there is plenty of heartbreak, there is joy, particularly with her own self-made independence, from the block of apartments she buys to gain financial security, her trips to the Randwick races with other women, and when driving her little Fiat. Dolly is a pioneer in many ways and the frustrations she endures paves the way for her daughter Nance and other women to lead more fully realised lives. Grenville captures Dolly’s contradictions perfectly, whether it be the pleasure she experiences in solving problems often left to men or the awkwardness she experiences with her children. We experience Dolly’s feelings along with her struggles to display them:

The words were silly, feeble, a thin pale little phrase trying to stand in for other words that she couldn’t find. Words that would build a bridge to this young woman standing there on the platform with her smart little suitcase, the way she herself had stood on the platform at Currabubula all those years before, about to go off into her life. Look after yourself: what that really meant was You are precious to me, but the depth of her feeling was made shallow by the glib phrase. (184)

Given the years that Dolly lives in from the 1880s to the late 1950s, there is naturally a great backdrop of history. The Free Education Act was introduced in 1906, both World War One and Two happened, along with the Great Depression, and the suffragette movement. Dolly is of course directly impacted by these events, and it is so much more interesting to follow their impact from an intimate and domestic perspective than to read about dates and campaigns. Dolly’s story of being tricked into marriage and denied education and vocation is both ordinary and extraordinary. Her restlessness makes a terrific scaffold for the many pubs she and her husband Bert take on from the Botanyville Hotel in Newtown, the Queensland Hotel in Temora, to the fancy Caledonian in Tamworth – all real places which, for the most part, Dolly and Bert managed to transform, primarily through Dolly’s cunning and tenacity and maybe a bit of Bert’s unhealthy charm.

Restless Dolly Maunder is an easy and fast-paced read. It may be labelled as fiction, and certainly Grenville uses all of her narrative capabilities to create such a compelling character, but the book is as much a story of Australia’s history as it is the tale of a strong, intelligent and thwarted woman whose struggles helped transform the lives of generations to follow. There’s a sense that in recreating her grandmother with an empathetic and careful eye, Grenville is also healing the past.