Reviewed by Ruth Latta

Reviewed by Ruth Latta

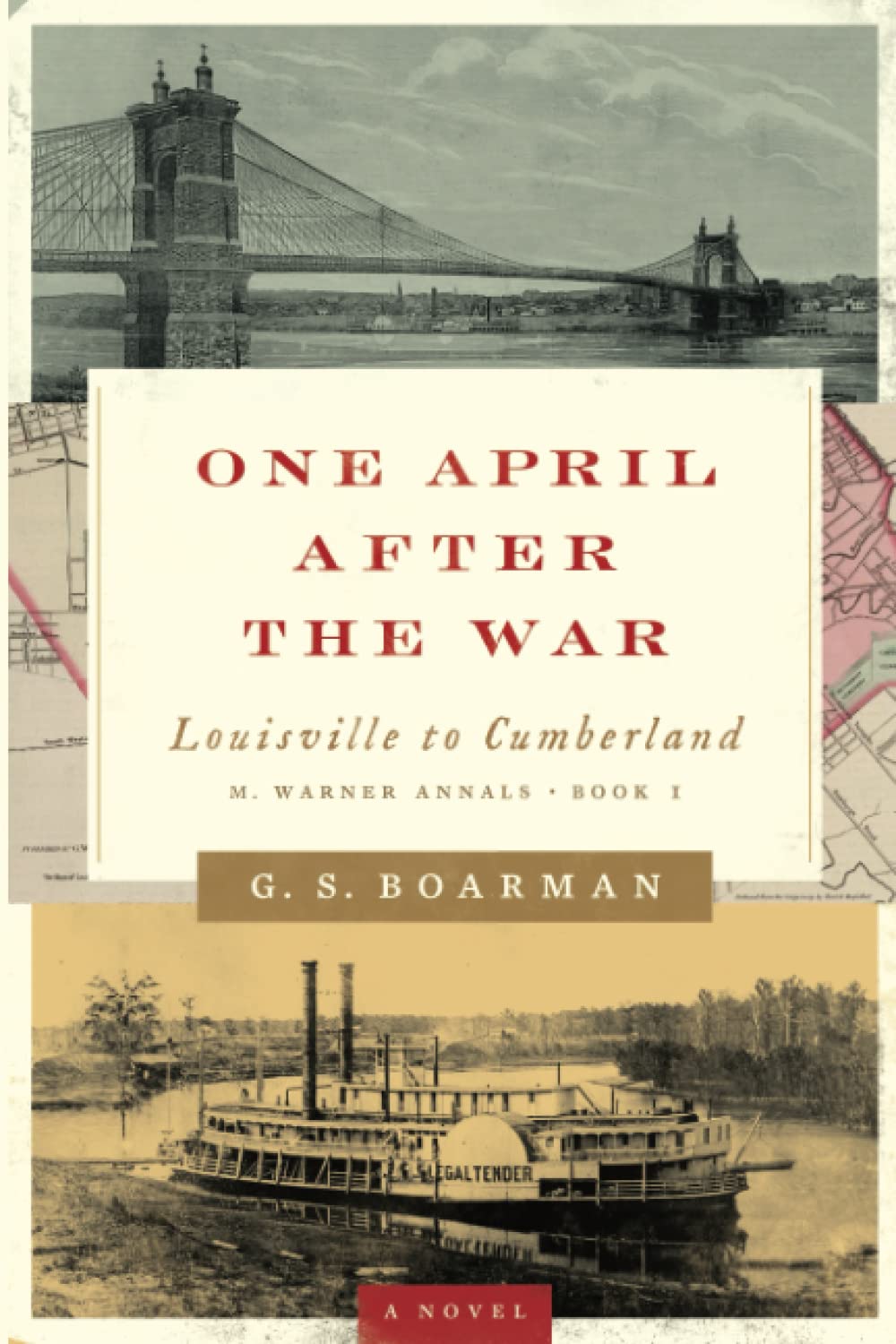

One April After the War:

Louisville to Cumberland (M. Warner Annals)

by C S Boarman

Bowker

ISBN 978-0-9600649-3-9, March 22, Paperback, 342 pages

One April After the War is a fascinating historical novel that takes the reader on a journey from Louisville, Kentucky to Cumberland, Ohio during the first two and a half weeks of April 1870. The Civil War is over but its impact upon the American nation remains.

As the novel opens, two Treasury Department detectives, Merritt and Argent, who have been in pursuit of counterfeiters in Cincinnati, are annoyed to be given a new assignment, to bring Miss Mary Warner to Washington to meet with President Ulysses S. Grant. The two men arrive at her family farm in Kentucky, imagining that she will be impressed by this invitation. They are disappointed.

Mary Warner, the co-protagonist of the novel, along with Merritt and Argent, is a strong, compelling character, definitely not the mild, acquiescent woman that men approved of in the late nineteenth century. Dressed in trousers, sullen and abrupt, she tells them that she doesn’t recognize Grant as her president because as a woman she is denied the vote. Since her father’s death in 1865, and with the loss of her siblings to death and to marriage, she has been running the family farm with the help of her two free Black employees, a couple named Carrie and Henry, who take a parental interest in her.

All the men know of their assignment is that they are representing the president on “a private matter. They learn that Mary is Grant’s god-daughter but that she has fallen out with him. When she takes off on Emmett, her horse, Carrie and Henry fill the two men in on her situation. After her mother died, the little girl was allowed to run free with her brothers and has always been rebellious. During the war she tried to pass as a boy and join the Union army. At one point her father threatened to put her in a convent.

Mary says it’s impossible for her to leave the farm with spring planting so near. Also, she is worried about a local man who intends to appropriate some of her land to build a railway. When Henry convinces her to go to Washington, D.C. to ask the president for help in fighting this matter, she finally agrees. She, the Treasury men and Henry set off to the railway depot to begin their journey.

Throughout the novel, the author’s exhaustive knowledge of the era’s politics, technology, social mores, and the geography of Kentucky and Ohio, come into play, with the result that the reader is totally immersed in the historic setting. We learn that, in spite of the Union victory, Black people are still discriminated against. For example, One example they get to Covington, where they are to catch the train, they enter a restaurant, only to find that Henry, being “coloured”, isn’t allowed in. Though Kentucky was on the Union side in the Civil War, there is a lot of anti-federal sentiment around and ex-Confederates hold the highest municipal and state offices.

A Kentuckian, Mary says, “I am sick to death of being reprimanded by ex-Confederates for holding to the Union and then in turn being reprimanded by Northern victors for being so close to rebels that I must have absorbed their blasphemy.”

Throughout the rail journey, we readers, along with Merritt and Argent, get to know Mary better. When Merritt asks her, “What of marriage and children?” she says she has declined all offers because men “expect so much of women” in marriage, “when they themselves have to give up so little. I like men. I like children. I don’t like the law, either civil or moral, that determines my place among them.” Throughout the journey, the omniscient author shows us Mary’s thoughts, which reveal her pureness of heart: she is a devout Catholic who wants to attend church on the days leading up to Easter; she is concerned about her horse in the stock car, and she grieves for lost family members

On the eight hundred mile train journey, everything that can go wrong does go wrong, and in the process we learn about railway travel of the era; various customs and the features of the towns and cities en route, while anticipating Mary’s next escapade. In Cincinnati, while Argent and Merritt are attending a trial to do with the counterfeiting investigation, Mary goes sightseeing, and after a series of accidental events, is arrested and jailed for disorderly conduct and indecent exposure. They lose some time in Cincinnati on account of Mary’s court appearance and because her lawyer and his family ask her to attend Palm Sunday Mass with them.

At Athens, Ohio, an intruder into their private drawing room on the train fills Argent and Merritt with concern, as they are carrying with them a quantity of counterfeit funds, which they use when gambling in the hope of luring counterfeiters, with the long-range plan to catch others higher on the distribution and production train.

Finally they reach the private railway car sent by President Grant to take them the rest of the way to Washington. Mary has her own car, outfitted like a stylish two room apartment, while the men share the adjoining car. When she becomes aware that they are locking her in at night, she resolves to get away from them and go home.

Matters come to a head on Easter Saturday in Cumberland, Ohio, where Merritt and Argent have been ordered to go undercover to the dodgy part of town to contact someone in the counterfeit ring and collect information to bring to Washington. Meanwhile, Mary has plans to escape in Cumberland. The tense “open” ending shows us once again Mary’s good qualities, and leaves us wanting more. Will we ever find out why President Grant wants to see Mary? It’s good to remember that the novel is subtitled, “M. Warner Annals, Book I.” With luck, Book II will follow soon.

About the reviewer: Ruth Latta’s latest Canadian historical novel is A Girl Should Be (Ottawa, Baico, 2021, info@baico.ca, ISBN 9781772162691