Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

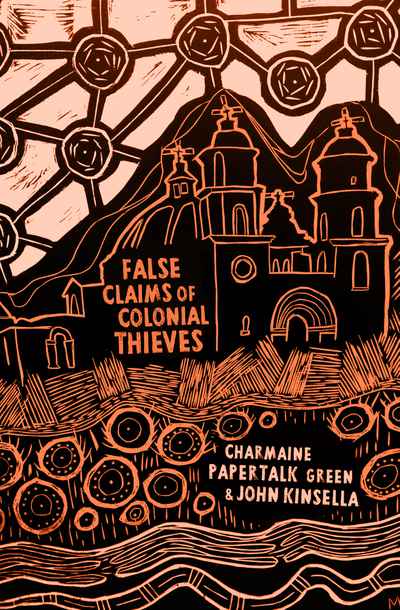

False Claims of Colonial Thieves

By Charmaine Papertalk Green and John Kinsella

Magabala Books

March 2018, ISBN: 9781925360813, Paperback, $24.99, 168pp

Charmaine Papertalk Green and John Kinsella couldn’t have more distinct poetic voices. Kinsella’s work tends towards the intellectual, abstract and often philosophical, requiring a few readings to reach full impact, while Green’s tends to be direct, intense and immediate, sometimes employing rhyme, traditional language and metres. Both come at their subject matter in very different ways, and yet there’s a correspondence between their styles, their approach, the subject they choose to explore both jointly and individually, and the way they respond to one another that works perfectly in False Claims of Colonial Thieves. Though the poems stand alone and many have been published in literary journals that way, it’s the dialogue itself where the most important meaning happens. Both poets take on similar subjects of dispossession, occupation, the landscape and ecology, exploitation and historical revisionism. Both poets ultimately situate the work as a search for an identity born out of pain, guilt and suffering, and both respond through the others work to create connection and reconciliation.

Aside from the jointly written epilogue, the poems remain distinct, identified by the initials at the end of each poem or poem cycle, though the poems often refer to one another, or riff off the same subject heading, so that the reader gets two perspectives of a place, a person, a topic or an historical event. These include poems about ancestors, about the architect and clergyman John Hawes, about Bottlebrush and other floral and native landscapes, the shopping centre carpark, the nature of colonialism, on mining, the Ellendale pool, and on the nature of “yarning” – a seemingly simple concept that mirrors the structure of the book itself and provides a way of healing:

Yarning is a beautiful conversation

From that moment

That space

That time (“Simply Yarning”)

Though there’s a pastoral thread running through the work, and many moments of beauty — Red-tailed black cockatoos, eucalypts and sheoaks, wildflowers, and ochre, this collection is not bucolic. There is always a sense of the many layers of truth and lies that make up any particular scene, and a deep exploration of what was lost in order to build the present:

Those of us with colonisers

as ancestors look or ways to retell

their stories, to build hope. But the fact

is in the railway, the ore crushers,

the shafts sunk into country. (“Grandmothers”)

Hawes, aka “God’s Intruder”, for example, is no hero in this work. An architect and priest whose many buildings in Western Australia are lauded as part of the Monsignor Hawes Heritage Trail, he’s clearly one of several colonial thieves that populate the book including mining companies, politicians, governments, the “state”, drug dealers, the police, developers, Joseph Bradshaw, Randolph Stow, settlers, and of course Pauline Hanson and the One Nation Party. Green and Kinsella pull no punches in calling out the pain and destruction caused by greed, the demonstration of power and subjugation for “progress”:

Foreign church structures rose

Dominating the landscape

Family showed me the quarry

From which rocks were taken

Building the Whiteman’s worship place

Mullewa Reserve nearby

Along the Mullewa – Morawa Road

Aboriginal hands helped build that temple

Their energy and sweat is in them rocks

Their heart is in them rocks

Hawes didn’t do it on his own

Wonder if that is written anywhere? (Hawes – God’s Intruder 4)

Anger and activism pervades the poetry, along with a clear recognition that the answer is not in a simple didacticism or binaries but instead allows for the multiplicity and complexity of poetic consensus and dialogue. That isn’t to say that the guilty parties aren’t clear. Mining remains a constant thief, taking from the earth, the local communities, and the world, both in terms of the actual damage it does, and in terms of the way it represents power structures, dominance, imbalance, and exploitation:

I can only

see them as the harrowing of Hell,

the opening of the land to release

what shouldn’t be released,

a desecration of spirit and place.

This is no small-scale intrusion

for the sake of community,

but open slather, a ripping out,

an extraction to fuel the world’s end. (“Grandmothers”)

Kinsella and Green pivot their anger, activism, and sorrow against the search for a personal identity in a way that almost comes across as autobiography. Though the poems are autonomous and sometimes fierce, there is an overall tenderness that adds a great deal of richness to the book. Both poets are ultimately searching for a true history; one that goes far deeper than rhetoric and the celebration of colonial gains got through poison, subjugation and thievery. In doing so, they create a new history that touches on not only what divides us–and there’s no ambiguity about that–but also what unites us: “all living things of the world joined together: land, water, air, spirit.” False Claims of Colonial Thieves is a book about many things – it asks the reader to reconsider history, dogma, and the blindness of privilege – to pass through anger and pain and open to hope, to language, and to love:

Language and the bush –

We heard the words and knew Poetry as an artform

Was intended to make up

For what was lost in the taking.

Language and the bush – (“Histories”)