Reviewed by Ruth Latta

Reviewed by Ruth Latta

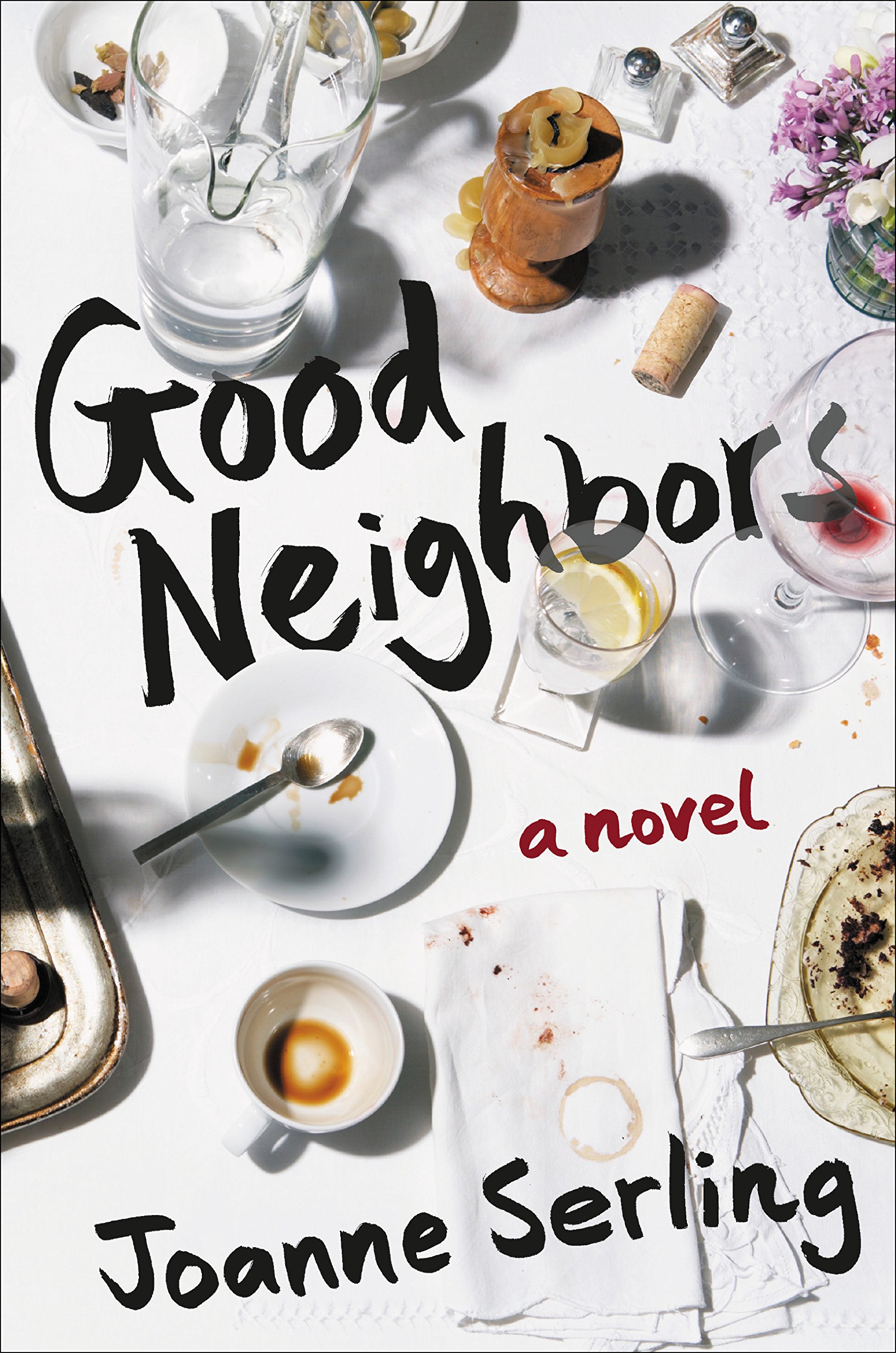

Good Neighbors

by Joanne Serling

Twelve (Hachette)

Feb 2018, ISBN 978-1-4555-4191-1, Hardcover, 256 pages

Nicole, the narrator of Joanne Serling’s new novel, Good Neighbors lives with her husband and two boys in an upscale Massachusetts suburb and is delighted that hers is one of four families in the neighborhood who have come together as a circle of friends:

We knew we would never have been friends if we didn’t live on the same street at the same time with kids the same age, but we were happy to have found each other,” she writes. Yet [we were] “convinced that our friends could do for us what our spouses were supposedly doing but simply couldn’t; alleviating the boredom and the isolation of middle age, helping us to navigate…parenthood.

The seven adults in the circle are the most successful members of their families of origin and have more in common with each other than with their relatives. All remember their parents as “hopelessly authoritarian, yet clueless and also uninterested in parenting.” As it turns out, however, one family’s failure at parenting shakes the group to its foundations.

Paige and Gene Edwards, the wealthiest in the circle, and often take the lead in planning lavish get-togethers for the other families. Nicole, Lorraine and Nela, the other mothers, are sometimes irritated by Paige’s bossiness and free-spending ways. At a group get-together early in the novel, Paige announces that she and Gene are adopting a four year old from Russia. They had wanted to adopt a sibling for Cameron, their seven year old son, but have been on an agency’s list for so long they’d almost forgotten about it.

Nicole had wanted to adopt rather than have her own children (possibly because of her troubled family of origin) but her husband, Jay, refused, fearing “bad genes’ and “taking on an unknown story.” Their two sons are in elementary school. Nicole believes that Paige and Gene are performing a “daring and wonderful rescue” for a child, and her estimation of Paige rises.

The four year old who arrives is not the blond cherub Nicole has imagined, but has a crumpled face, a running nose and a lazy eye. Prior to introducing her, Paige leaves notes in her friends’ mail-boxes instructing them as to what terms to use in speaking about their new daughter. The other families are not to tell their children that the child was “given away” to an “orphanage”, nor refer to her Russian parents as her “real parents”. Instead, they should say that the little girl has “biological parents in Russia who couldn’t keep her.” Despite this display of concern, the Edwards do not retain the name that the child knows herself by, but rename her “Winnie.”

When the friends gather together for dinner to meet Winnie, Paige mentions Winnie’s troubles adjusting. When Winnie appears in pyjamas, looking “playful, charming, [and] a little bit devilish”, she goes straight to her father, Gene. Throughout the novel, Gene seems to like Winnie better than Paige does. When Nicole engages Winnie in a game of Peek-a-boo, Winnie puts her table napkin on her head and Paige scolds her sternly. When Winnie flings herself into Nicole’s outstretched arms for a hug, Paige says, “She’ll hug anyone. it’s part of the orphanage thing.” Later she says that she and Gene didn’t ask for a “special needs” child.

Dramatic tension builds as the reader, like the neighbors, see Paige treating Winnie, as one neighbour puts it, as a “second class citizen”. Are the problems normal in an adoptive situation or is Paige mistreating the child? Nicole tries to help by offering to take care of Winnie occasionally when Paige and the nanny are otherwise occupied, and the two afternoons they spend together are a pleasure for both. Though Nicole loves her sons, she is drawn to the little girl, who blooms in her care, coming across as cooperative, bright, social, and affectionate.

Nicole, however, has commitments to both her nuclear family and her extended family in Ohio. Her husband, Jay is a playmate to their sons, but fails to support Nicole on their behavioural issues. Her sister, a music teacher and addict, keeps borrowing money from Nicole to get her life in order, but never does. Their mother, in poor health, is highly critical of both her daughters. Nicole listens to their outpourings on the telephone and tries to be of help.

The escalating troubles end in tragedy, leaving Nicole and her friends searching their souls and second-guessing themselves. Were they unsupportive and judgmental toward Paige, as she alleges? Was Winnie really “too damaged” to fit into a family? Given Nicole and Winnie’s warm interactions and the neighbors’ ongoing concern throughout the deteriorating situation, the answers to these questions seems to be “No.”

Serling’s novel is as compelling as other good recent novels about parenting, such as Tom Perotta’s Little Children and Meg Wolitzner’s, The Ten Year Itch. In Good Neighbors, we see how the yearning to fit in can blind us to our friends’ flaws.

About the reviewer: Ruth Latta’s novel, Grace in Love (Ottawa, Baico, 2018, ISBN 978-1-77216-128-1), is available from info@baico.ca