Reviewed by Chris Viner

Reviewed by Chris Viner

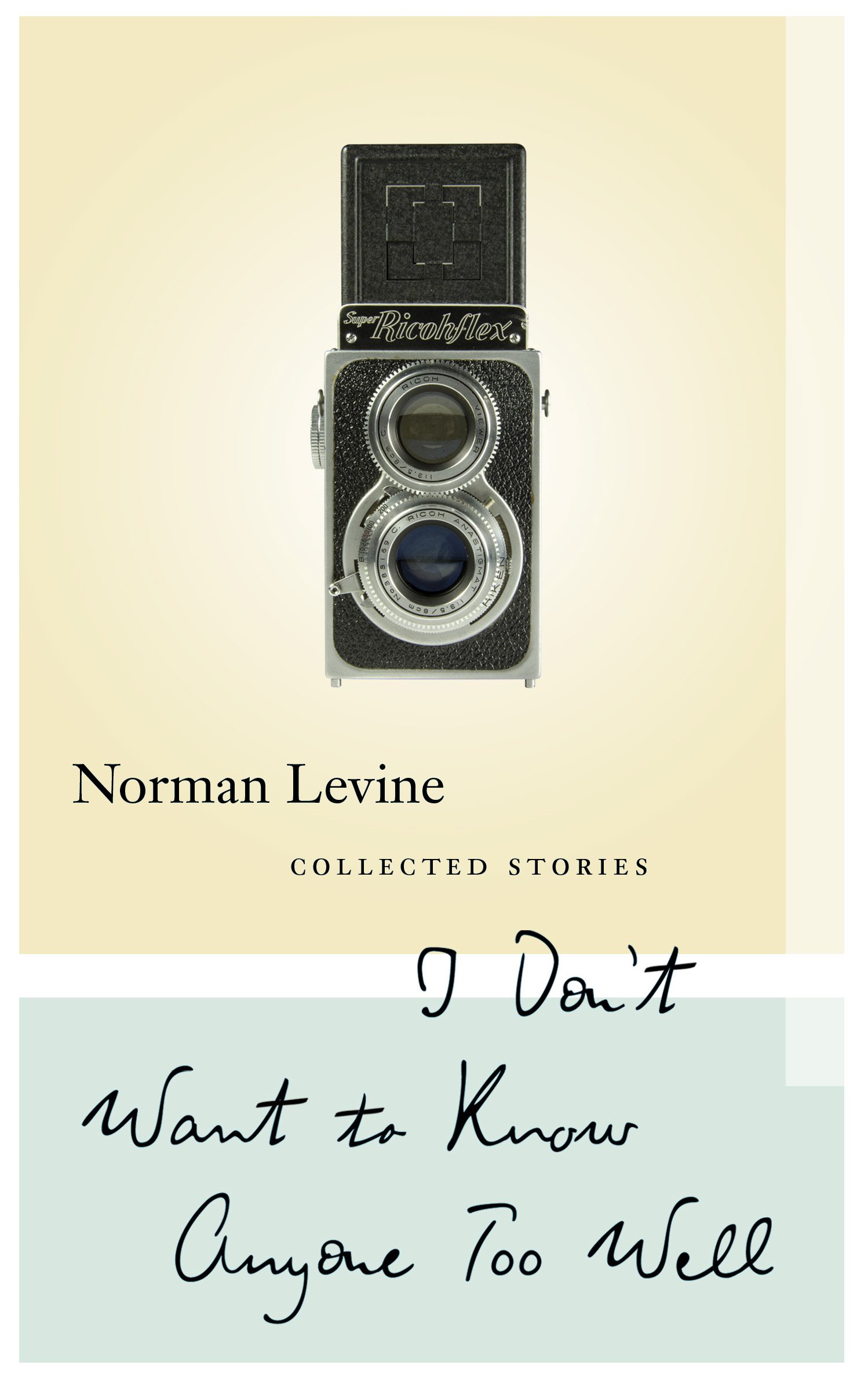

I Don’t Want to Know Anyone Too Well

Collected Stories

by Norman Levine

Biblioasis

December 2017, 580 pp, ISBN-13: 978-1771960885

The joke in Norman Levine’s posthumous short story collection, I Don’t Want to Know Anyone Too Well has surely one of the most chilling, stalling effects in modern literature. Levine’s world is cold, it is a transatlantic, bureaucratic world of coastal publishers that gossip over contracts and writers and promiscuous BnB hosts that bed off-duty soldiers. Here, everybody is a stranger, and it’s better they remain that way.

The axe that comes break us, the weight that shifts the frozen sea, finally, is the deep loneliness portrayed in the characters attempts at telling each other jokes. And Levine, like no other writer, manages to convey, squarely, through this single, sad, common reaching out at strangers, the horrific fear scarred across the nervous system of the post-Munch, post-Bacon, human condition. That condition, it seems, is loneliness, and it weighs on us, in Levine, most poignantly through the frail passing of an awkward attempt at humour. The first two stories, ‘A Father’ and ‘In Quebec City’, end with characters telling jokes. And what should feel like union, feels like the end of the world:

“You used to tell me jokes, Mendel,” I said. “Where did they come from?”

“From the commercial travellers. They come to see me all the time. All of them have jokes. I had one this morning. What is at the bottom of the sea and shakes?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“A nervous wreck,” he said and smiled. “Here is another. Why do cows wear bells around their necks?”

I said nothing.

“Because their horns don’t work.”

In Levine’s work, the light joke, becomes the pivotal symbol for all that it embodies and decodes for us about how we behave around each other, the failure of connecting, the inevitable loneliness of settling for whatever happens. As these quotidian, short-lived attempts at union collapse, so do our plans, and our predictions. Lives in these stories never turn out as expected, but they do have the accomplish, the finish, of a life that feels real; sometimes to the point of unbearable pain. Whether it be an old friend that the protagonist bumps into that he can’t connect with, or a father whom he wishes not to be similar to in anyway, for his lack of power, these characters resonate with the human flicker of reality; the chaos that lurks behind the ordinary lives of strangers.

The description of industrial connectivity through modern transit clashes against the thick strokes of the coast, and even more so against the tortured pallet of the men and women who populate the stories: all seem to have lost something, whose detail they have forgotten—to the point where the only thing they seem to be aware of is that the thing they have lost was precious. In ‘Champagne Barn’ a mother is dying; she wants to both carry out her imminent death with as much practicality as possible, by helping her children, whilst also failing to comprehend any tragedy inherent in the situation. She seems to exist in two places at once. And the result, the portrait that is conveyed, is one of existential terror.

It is no wonder, then, that he was a good friend of Francis Bacon’s, the man responsible for skewed portraits described by a Prince Charles as “awful.” Levine wanted to capture that same immediacy that he saw in painting, he wanted to flare up the nervous system with flashes of everyday life, awful portraits of its sadness and subtle confusion swimming beneath the surface. He is so successful, that whilst reading these stories, one feels a sense that one is hardly reading at all—that the words written on the page have been scored somewhere between the invisible layer of the painfully visible and the necessarily unspoken. The prose is so clean, it carves like a knife into reality, and performs an autopsy on modern reality and social behaviours, so correct, it almost seems like it might, for a moment, bring the stifled, post war, nuclear world, back to life, back into some kind of awareness of what has been lost and what cannot be found.

During the eponymous story, the reluctant, unnatural social interactions between two characters shoehorned together, becomes odder the more realistic it gets. Al Grocer has lost his pen, and in their shared pursuit of a new one, the two men begin, slowly and subtly, to discover sides to one another that they like less and less. The story plays out like one of those no-days that you had very nearly forgotten:

We came out and walked along the front.

“I think we can get a biro,” I said, “in Literature and Art.”

“But I’ve got one.” And he brought out from his fawn jacket pocket one of the plastic pens that were on sale in Woolworth’s. “What’s the matter,” he said good-humouredly. “Haven’t you ever taken something without paying for it?”

These distances, as stories navigate St. Ives, Ottawa and Montreal, push characters further away. What we are left with is an awareness and validation of the outsider, and the condition of separateness. But whilst these portraits create a reality so accurate we not only see the flesh but the nerves below, there is a redemption to be had behind the bleak separateness on display, in every town, in every house, on every train. Because at the heart of this unique collection is a beautiful message: the real—and rare—connection is worth the search.