Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

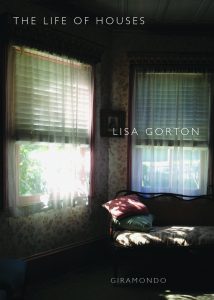

The Life of Houses

By Lisa Gorton

Giramondo

ISBN: 9781922146809, Paperback, 224 pages, April 2015

Lisa Gorton’s writing is always condensed, regardless of whether it’s poetry or prose. Each word feels carefully chosen, pregnant with multiple meaning and nuance. Gorton’s latest book, The Life of Houses, almost reads like a verse poem at times, moving between the point of view of its two key characters – a mother and daughter. Anna is the director of a Melbourne art gallery. When her husband leaves her to go stay with his mother in England, Anna begins an affair with Peter, a Sydney lawyer. The story opens as Peter has left his wife and come to visit Anna in Melbourne. Anna doesn’t want her teenage daughter Kit to know about the affair, so she sends her to stay with her parents in the small seaside town where Anna grew up, and hasn’t visited for many years.

The novel is structured with Anna and Kit having mostly alternate viewpoint chapters. The book has an interiority that is detailed, sensuous and almost Woolfian. Sentences flow in stream-of-consciousness observations, evoking mood, detail and a gentle rhythm that’s hypnotic: “the wind was tearing white crests from the waves. Closer in, a gull held at a point, wingtips quivering.” (118)

There’s a clear connection throughout the book between Kit and Anna as characters: their lives intersect and link even when they’re apart. While staying with her grandparents and aunt Treen, who has moved back home to look after their ailing mother, Kit begins to discover aspects of her mother that she didn’t know. She also begins, through that lens, to explore her own life. The novel delves deeply into the mother-daughter relationship, not only exploring the way these characters interact, but how their perceptions of the other colour the way they perceive themselves. Both Kit and Anna share an artistic eye for fine detail, an intense introspection that often slides into discomfort, and a quiet carefulness, which reveals itself as a kind of passivity, that begins to disintegrate as the novel progresses. Anna has tried to distance herself from her family and “re-invent” herself, but she finds that those DNA strands are as solid and pervasive as the house she grew up in. There’s a quantum entanglement between Anna and Kit. Both are continually surprised to find themselves in the places or situations they seem to slide into , and both seem in continual wonderment that the world exists for others; that people are solid and real, outside their perceptions:

Kit had suddenly seen what was almost impossible to believe, that the past had existed really. Here, she thought: her mother had stood here. She touched the bark. Here, in this dust-hased shade. (119)

Throughout the novel, the prose is incandescent, delicate, and beautiful. Many passages are so tightly wrought, they could easily be put into stanzas and called poetry:

The shade, now that she was in it, was less like darkness than like smouldering light. Everywhere thin shafts seemed to give off smoke in the dusty air. There was no grass; the dirt was soft with dry brown needles. The tree’s branches barely moved in the wind. (119).

The book is full of dichotomies that underpin the story. There is the old (lost) money of Anna’s family versus the newer money of Anna’s old school mate Carol and her pretty daughter Miranda; hotels versus homes; city versus country; gallery art versus amateur art as typified by the art lessons Scott holds; modern versus old-fashioned; interior versus exterior; light versus dark; marriage and stability/status-quo versus the transitory nature of an affair. The tension between these opposing forces is dramatic and subtle at the same time, propelling the plot and creating a highly textured read full of sensual power.

As the title suggests, this is very much a book of places and spaces–one that explores the way in which we are impacted by the spaces we inhabit and how they leave an imprint. The specific items in Anna’s house that her father has collected with such care, the art on the walls, or the heavy furniture that makes the rooms “crowded” are all lingered over with a tenderness that is almost anthropomorphic. Kit wakes early and walks through the darkness of the old, majestic and haunted house she is told she’ll inherit. She feels the weight of that inheritance as a burden as much as a gift, trying to find herself through these spaces and artefacts. Anna wakes in the hotel she’s staying in with Peter and feels lost in the impersonal space:

She had woken early in the hotel’s upholstered silence and imagined her own house uninhabited, its curtains open, moonlight marking the shadow of the window frame on her bedroom floor. Half asleep still, the image had held for her a dream’s power: the house less a place than a cluster of habits belonging to the left and right, upstairs and down: the place where she became free of her bag, where she stood with a knife in her hand, where she sat down with a drink. Dry-mouthed in that hotel room, its air-conditioning, its soft light, she had felt an isolation as sudden as terror. (32)

Later Anna is finally forced to return to her family home and is overwhelmed by the familiarity – the sense of home aligned with a sense of self: “Suddenly that view, so familiar that seeing it again was less like seeing it than rediscovering it within herself: that uneven curve against the thin pale blue summer morning sky.” (183)

Both Kit and Anna transform in unanticipated ways as they discover themselves through the book, through their relationships, through what they’ve hid from each other and themselves, that begins to reveal itself through tragedy and loss.

Though the book reads quickly, it’s denser than it feels. As a reader, I felt it was necessary to slow down my reading so I could notice all the descriptive detail and the power in each word in The Life of Houses, allowing the story to unfold at its own rhythm and get fully under the skin. This is an utterly beautiful and somewhat sad story that grows in power with re-reading as it strikes at the heart of human relationships, families, self-perception, and how we make meaning in our lives.