Reviewed by P.P.O. Kane

Reviewed by P.P.O. Kane

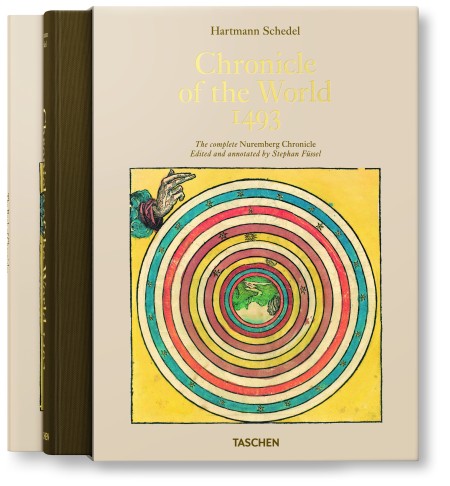

Hartmann Schedel

Chronicle of the World – 1493

Edited and annotated by Stephan Fussel

Taschen, 2013

ISBN: 9783836544498

This is a beautifully produced facsimile of the German edition (it was apparently published in Latin at the time as well) of what has come to be known as the Nuremberg Chronicle. The book sets out to tell the history of the world through seven ages, though the seventh is best described as the age to come, when we can look forward to the coming of the Antichrist, Armageddon and the Last Judgement. Seems crazy to most of us, but these were all very real prospects for Hartmann Schedel and his contemporaries. Most attention is paid to the sixth age, running from about the birth of Jesus Christ up to the perpetually-changing present.

Martin Luther (1483-1546) is likely to have read this book, that’s the thought that first strikes you. There’s one telling report here, an account of a peasant preacher who decried priestly privilege in a sermon delivered at the village of Niklashausen in 1476 – less than two decades before the book was published. He was burned alive for his outburst, but that small speech was a sort of precursor to the Reformation. Also, at certain points within the Chronicle there are anti-Jewish stories (e.g. an account of the murder of a Christian child at Passover, reported as fact), sentiments and (crucially for the dissemination of this stuff) images and we know (not least from reading chapter 7 of David Nirenberg’s Anti-Judaism) that Luther was not above expressing such sentiments in his sermons. In this as in certain other respects, the Chronicle is a document that is of its age.

The images will be the main attraction of the book for those who don’t read Middle High German, so a few words about them. There are about 1800 hand-coloured illustrations and they can be found on every page. Some are rather pedestrian and workmanlike but very many are wonderful and not a little weird. No less an authority than Panofsky has put forward the notion that Durer may have had an involvement in creating a few of these images. We know that he was an apprentice in the workshop of Michael Wohlgemut, one of the two principal artists charged with illustrating the Chronicle. Especially striking are those that grace the seventh age: monstrosities in the sky, engaged in enraged combat; skeletons performing a dance of death. The great cities of mainly Germany and Italy (as the map of Europe is drawn now) are also illustrated; and it was heart-warming to see the Stephansdom dominate the cityscape of Vienna, as it does even to this day. The city walls are now long gone, mind.

Stephan Fussel’s accompanying booklet (above) was extremely useful in making sense of the Chronicle. He set out the background to its publication and picked out myriad topics of note within it, not least the story of the rise and dissolution of the Knights Templar. His erudition and insight were everywhere apparent.

Chronicle of the World – 1493 is a fascinating historiographical work, at its best nothing less than a grand periodic narrative (post-Hesiod, pre-Vico), a valiant attempt to make sense of Creation. Its publication gives us a window into another earlier world, a world as strange as our own.

About the reviewer: P.P.O. Kane lives and works in Manchester, England. He welcomes responses to his reviews and you can reach him at ludic@europe.com