Twelve Days of Transfer tells the story of Kedney’s own unsuccessful attempts at carrying a child, the complex emotional responses to the inability to conceive, the guilt, the grief, but also the relief. She writes about her experiences in grief support groups and with friends, as well as her own complex IVF experience.

Twelve Days of Transfer tells the story of Kedney’s own unsuccessful attempts at carrying a child, the complex emotional responses to the inability to conceive, the guilt, the grief, but also the relief. She writes about her experiences in grief support groups and with friends, as well as her own complex IVF experience.

Category: Poetry Reviews

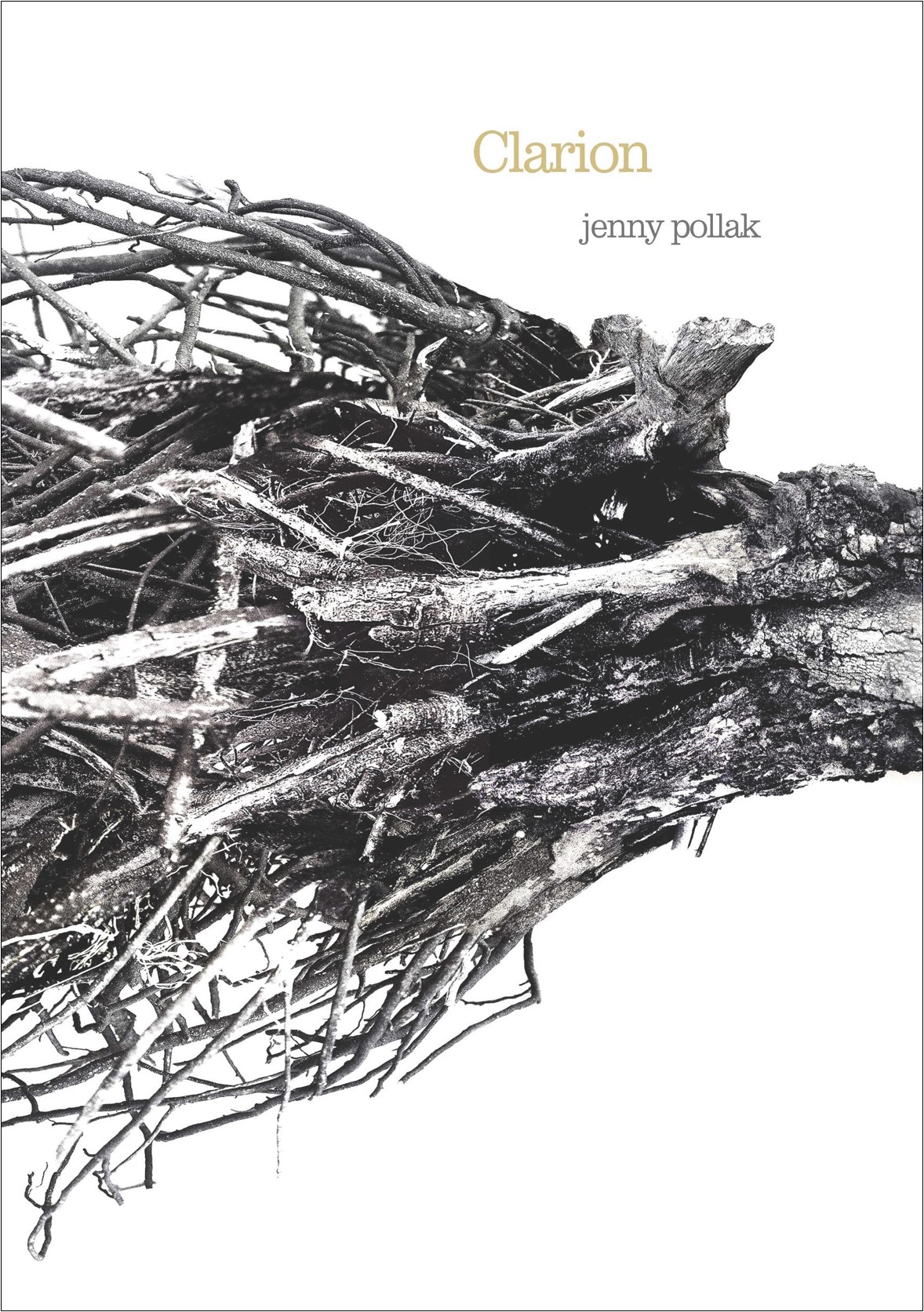

A review of Clarion by Jenny Pollak

This book is a poetic and visual artistry, it is also a love song shaped from nature’s elements — sand, salt and time. Pollak reminds us that sticks, though broken, remain strong, wild and full of untamed beauty, capable of profound acts of resilience and grace.

This book is a poetic and visual artistry, it is also a love song shaped from nature’s elements — sand, salt and time. Pollak reminds us that sticks, though broken, remain strong, wild and full of untamed beauty, capable of profound acts of resilience and grace.

A review of Mycocosmic: Poems by Lesley Wheeler

Wheeler’s ideas synthesize unusual word groupings; from these combinations new qualities emerge, such as unpredictably jarring, sometimes funny internal and end rhymes, line breaks, and punctuation, not unlike the way speakers of a language are able to generate an infinite number of sentences from a finite set of syntactical rules.

Wheeler’s ideas synthesize unusual word groupings; from these combinations new qualities emerge, such as unpredictably jarring, sometimes funny internal and end rhymes, line breaks, and punctuation, not unlike the way speakers of a language are able to generate an infinite number of sentences from a finite set of syntactical rules.

A review of The Four Faces of Eve: A Tribute to Survival by Connie Boyle, Brooke Granville, Petra Perkins, and Gail Waldstein

I speak for Colorado when I say we see the weathering/ weathered faces on the cover of this book of poems because these poets have faced the sunshine, the rain and the freezing cold of life. We treasure this wall of women we may not know, yet we feel we do know them. They are our Eve, the source of all life, who eat the forbidden fruit, take God’s consequences and live to tell us about it.

I speak for Colorado when I say we see the weathering/ weathered faces on the cover of this book of poems because these poets have faced the sunshine, the rain and the freezing cold of life. We treasure this wall of women we may not know, yet we feel we do know them. They are our Eve, the source of all life, who eat the forbidden fruit, take God’s consequences and live to tell us about it.

A review of In The Thaw of Day by Cynthia Good

Good’s poems catch and return with these moments of praise and gratitude balancing the tension with hard-fought lessons and observations of resiliency from the natural world. Her poetry combines language that is intensifying and evocative, like a personal diary, with the immediacy of a scrapbook. And it’s this personal baring open and honesty that lingers on making In The Thaw of Day a dynamic collection.

Good’s poems catch and return with these moments of praise and gratitude balancing the tension with hard-fought lessons and observations of resiliency from the natural world. Her poetry combines language that is intensifying and evocative, like a personal diary, with the immediacy of a scrapbook. And it’s this personal baring open and honesty that lingers on making In The Thaw of Day a dynamic collection.

A review of As If Scattered by Holaday Mason

Mason quickly shifts into an influx of embodied imagery and sensuous detail; absorbing love poems, lush and erotic, are further enlivened, countered by a more objective perspective as landscapes of the natural world magnify the intimacy of Mason’s poems. The meditative poetic interchange using briefer lines, airy lineation and informal erasure drew me in through breath and space, encouraging a contemplative atmosphere.

Mason quickly shifts into an influx of embodied imagery and sensuous detail; absorbing love poems, lush and erotic, are further enlivened, countered by a more objective perspective as landscapes of the natural world magnify the intimacy of Mason’s poems. The meditative poetic interchange using briefer lines, airy lineation and informal erasure drew me in through breath and space, encouraging a contemplative atmosphere.

A review of Exactly As I Am by Rae White

The imagery captures the tender and quasi-ritualistic act of leaving pieces of oneself on another person’s life. The metaphor of clothing as both physical and emotional markers is clever and poignant, conjuring connection, memory and the lingering presence of love and yearning. The rhythm flows naturally with conversational ease while opening up new ways of seeing.

The imagery captures the tender and quasi-ritualistic act of leaving pieces of oneself on another person’s life. The metaphor of clothing as both physical and emotional markers is clever and poignant, conjuring connection, memory and the lingering presence of love and yearning. The rhythm flows naturally with conversational ease while opening up new ways of seeing.

A review of on a date with disappointment by Najya Williams

![]() Repetition is one of Najya Williams’ most important lyric strategies. Certain poignant lines are frequently repeated, giving them resonance, enriching and amplifying their meaning. Take “but the memories,” for instance, a poem about heartbreak and resilience. “But the memories have long scabbed over” is repeated five times in this 27-line poem, italicized in the final line. “The scars may never heal — fully at least” is repeated four times.

Repetition is one of Najya Williams’ most important lyric strategies. Certain poignant lines are frequently repeated, giving them resonance, enriching and amplifying their meaning. Take “but the memories,” for instance, a poem about heartbreak and resilience. “But the memories have long scabbed over” is repeated five times in this 27-line poem, italicized in the final line. “The scars may never heal — fully at least” is repeated four times.

A review of Magicholia by Jenny Grassl

These poems challenge our preconceived notions and prescribed roles with fascinating imagery and provocative language that introduces Grassl own invented syntax. This unique use of language takes on visually significant forms. The subject matter encompasses dangerous and threatening conditions such as betrayal, life-threatening mental illness, the rigors of treatment, incarceration, and the end of the world.

These poems challenge our preconceived notions and prescribed roles with fascinating imagery and provocative language that introduces Grassl own invented syntax. This unique use of language takes on visually significant forms. The subject matter encompasses dangerous and threatening conditions such as betrayal, life-threatening mental illness, the rigors of treatment, incarceration, and the end of the world.

A review of Review of God is a river running down my palm by Jeremy Ra and Aruni Wijesinghe

Poetry offers universality, and the importance of this chapbook lies in how two very different people—in background, ethnicity, gender, perception, and voice—convey this universality. Not just in theme, but in desire.

Poetry offers universality, and the importance of this chapbook lies in how two very different people—in background, ethnicity, gender, perception, and voice—convey this universality. Not just in theme, but in desire.