Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

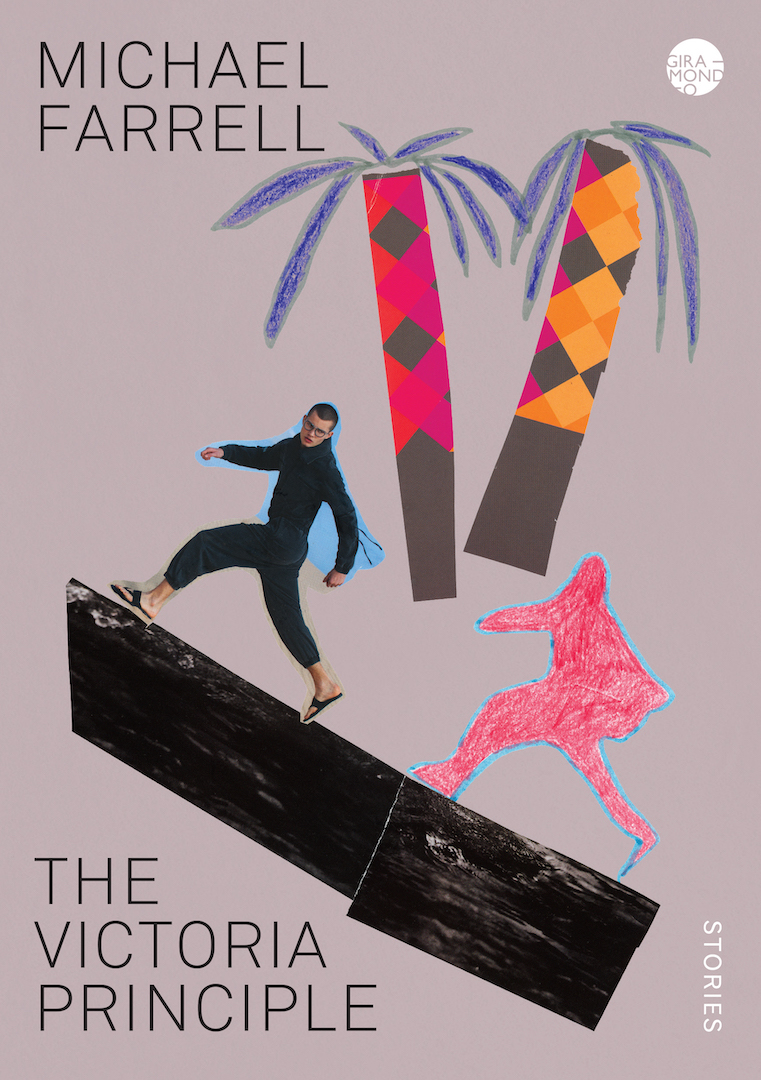

The Victoria Principle

by Michael Farrell

Giramondo

May 2025, Paperback, ISBN:9781923106307, 178 page, 29.95aud

The title of Michael Farrell’s new book, The Victoria Principle, is a clue to what a reader can expect from the book. Wordplay, pop-infused irony, surreal puns, and lots of kitsch are in play throughout the collection which lives up to Farrell’s trickster reputation. The title is a pun on the name of the queen of kitsch, star of US soap opera Dallas, Victoria Principal, whose slightly changed name becomes a rock band with songs dedicated to Melbourne suburbs: “The Geelong Principle,” “The Blackwood Principle”, “The Mansfield Principle” etc. While this is Farrell’s first book of fiction, presented as a series of stories, the work resists genre categories and they feel more like vignettes then what we traditionally call stories as they tend not to have a focused plot with a beginning, middle, and end, and rarely contain a climax. The first piece “Thinking About Ornithophobia”, reads as auto fiction with a great deal of verisimilitude. Val is a well-known writer who has been invited to edit a special fiction edition of a literary journal, and decides to choose Ornithophobia or an irrational fear of birds as his topic. As with many pieces in the collection, this piece encompasses description, gossip, snippets of conversation, and as with nearly all of teh pieces in the collection, a literary connection, in this case, exploring the work of Judith Wright followed by a visit with John Tranter:

Was cruelty, then, merely a side effect of the forces of the world—in some cases, at least? ‘Crows eat newborn lambs’ eyes,’ the country-born Sydney poet John Tranter had remarked to Val one evening at Lounge, in Melbourne. ‘Not all crows,’ Val thought of saying later. And Val found it easy enough to conjure human billionaires, kneeling in misty paddocks, sucking lambs’ eyes out, as a privileged treat. (5)

By keeping close to home, the pieces in this collection challenge notions of what is and isn’t real, undermining notions of memoir, which is a construct no matter how it’s labelled. It makes for consistently entertaining, and often challenging reading that encourages uncertainty. This shift between memoir, fiction and poetry feels seamless, challenging the reader to re-examine notions of identity, history art. Many of the stories read like extended prose poems or monologues without paragraph breaks and have a breathless, stream-of-consciousness feel, with run-on sentences that slide between thought-bubbles, dreams, memories, and character confessions to the reader or a therapist about mental and physical health crises with a surreal and often metafictional twist:

That’s a bit like if I, said Marvel, formed a band called Wrong Norma, after my grandmother, only to find, in the future, like at a corporate 2026 Christmas party Kris Kringle, that Anne Carson had published a big book of poetry scraps with Penguin titled that, after a slight poem of the same name, which related to Norma Desmond, the character played by Gloria Swanson, in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard. (“Talking To The Avant-Garde During Lockdown”, 105-106)

The references are extensive, from the contemporary novelists and poets peppered throughout the book like the Anne Carson and John Tranter example above, to literary critics like Marjorie Perloff, citations from Catholic iconography, Hinduism, Greek Mythology, theatre, art, and quite an extensive catalogue of music which is actually pretty hip. A playlist to go along with this book would not go amiss. There is no index or footnotes as the references are embedded into a fictional construct. The referent is sometimes fictional as well, and the reader who wants to know more about any reference will have to use a search engine. This isn’t entirely unpleasant though it can lead to rabbit holes which have the impact of extending the work beyond the pages, providing an academic essay feel to the work.

This story was, I suppose, a demonstration of the poetics of distraction, which reminded me of Ben Hickman’s theory of John Ashbery’s inattention. It’s another version, in a sense, of Harold Bloom’s theory of misreading. Ashbery might be said to have written his poems as inattentive repetitions of, say, Whitman, Stevens, Auden and Laura Riding, among others. (92, “The Victoria Principle, Or Andy Gibbons And Latin America”)

Much of the book does use details direct from Farrell’s nonfictional activities, particularly where the pieces move between story and literary commentary, for example, an editing gig for the literary journal Rabbit. Farrell did actually edit Rabbit 24 – LGBTQ+ (a literal Rabbit hole). The book is shot through with humour, often arriving at unexpected moments when the work seems particularly somber, like the desire to pour milk on Pambula beach “as if sand were cereal”, Dustin Hoffman donating a robot of himself to act in a rather surreal movie, or via dreamscapes like “Impatience Is Not a Virtue” which begins a simple story of inheritance that slowly unravels as the narrator’s dead father sits up in his deathbed with a rose for a head and complains about his eulogy. That particular piece contains a simulacrum of a child who is the grandson of a brother’s still youthful daughter come back from the future because he was impatient to be born:

The afterlife, where or whatever that was, had reserved some of his DNA so that the original VInayak could still be born in the future. The fake Vinayak was sterile, but could hold the senate together until the net, more sensible generation was born (52)

In addition to the kinds of koans indicated above, there is a great deal of linguistic play throughout the book. The title piece, “The Victoria Principle, Or Andy Gibb And Latin America” already cited, is one example, in which the work provides anagrams for Andy Gibb and Freddie Mercury: “Fir. Red. Ended. Dude. Dead. In Edinburgh, my English roundup could use rough yank.” Andy Gibbons dated Victoria Principal so there are layers of connections that may or may not be picked up by readers. The in-joke is a consistent motif throughout the work. If you don’t get it, Google is your friend, but if you do get it, there’s a certain sense of pleasure in being in the know, particularly against such linguistic fun:

And while the pronoun, or dare I say the character, that was the I, the narrator of this story, had mostly, so far, coincided with the author, it was perhaps my desire, the desire that writing represented — see, for reference, I didn’t know, probably Helene Cixous, and Luce Irigaray, if not Deleuze and Guattari – to go beyond the I of the author, and beyond the pedestrian (via fictional, or metaphorical, car or accident) – this was what writing a story was – into something more extravagant. (“Writing”, 98-99)

The Victoria Principle is not necessarily an easy book to read. It appears to be a simple set of stories following a straight trajectory until language begins to deconstruct, and the real and entirely unreal (as in unviable) begin to blur and blend. It is always a lot of fun though, shaking the reader from preconceptions and opening a new way of thinking about language and narrative.