Reviewed by Catherine Parnell

Reviewed by Catherine Parnell

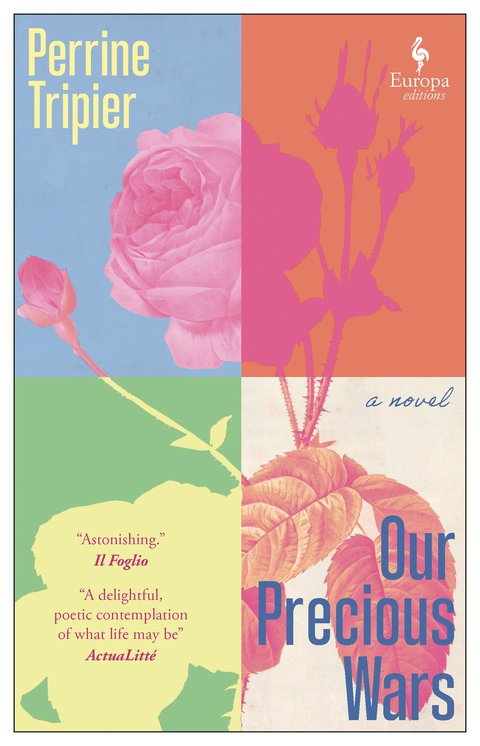

Our Precious Wars

By Perrine Tripier

translated from the French by Alison Anderson

Europa Editions

ISBN: 979888661450, November 2025, 160 pages, Paperback

In Our Precious Wars, Perrine Tripier writes powerfully about family and memory, and the contentious space they inhabit in our hearts. Translated from the French by Alison Anderson, this debut novel by an under-thirty author deftly imagines the plight of an older women, all the while pondering the enigmas of the time-tested self in our shrinking world. Isadora, in hospice, chronicles life at her beloved family “House,” only to find her perspective differs radically from that of her family. But that’s not the half of it – the novel is by turns sweet, sad, and loaded with attitude, but never saccharine. For Isadora fancies herself the keeper of all the keys and as such, turns an uncompromising eye on oppositional forces, be they weather or relatives. What she holds on high is her inherited House and land. Still, she gives herself away when she says, “There are places that harpoon you.” Isadora seems to be in league with the eponymous white whale, Moby Dick, sounding and diving the depths, lathed with whale line. A tangled-up survivor.

Written in the first person, the book interrogates the gulf between what is recalled and why it’s recalled – and slants toward the fickleness of memory and myopic perception. Tripier structures the novel in four parts corresponding to the four seasons. The novel opens in summer, universally viewed as a time of freedom, especially for young children. Of her childhood, Isadora remembers, “We let the days flow past like a stream of liquid light. It was a precious time of yielding hours, evanescent mornings, endless afternoons.” This haunted novel leans the precious against the turmoil, and the wars within – the sibling hierarchy and squabbles, the slight behavioral expectations imposed by the elders, the coming of age moments as the children, one by one, mature and leave the House, all except Isadora. When they return with children of their own, Isadora’s “spice of summer” becomes burned and accusatory. “Did they not remember anything? Did becoming an adult mean having to forget how ingenious we were as children, and wonder instead at the pale exploits of offspring who’ve invented nothing? I scowled…” By turns churlish and self-important, Isadora soon drives them all away and is left alone in the House for seasons, years, decades.

Many of Isadora’s memories circle around Harriet, her beloved younger sister, who loved autumn. Ever possessive, Isadora says, “She was mine, and the woods were, too, and those two entities could not communicate without me. I was the link, still am the link, between Harriet’s smile, which we have all forgotten, and the tall fir trees I’ll never see again.” Out of the extraordinary relationship between the two comes Isadora’s greatest pain, and when the cause is revealed, readers will be as broken as the hospice-bound woman. And like Isadora, they will have crossed the divide between what is recalled and why it’s recalled. Memory, colored as it is, becomes a call to the divine for relief from grief, a plea for grace cloaked in sentimentia – or perhaps an apology.

Although cloaked in solitude, especially in winter, Isadora once shares her bed with a tenant. As appealing – and helpful around the house – as men can be, she finds her own company sufficient, and with startling clarity realizes “winter loves” are nothing more than “the body’s survival instinct calling out for another warm body to snuggle up against.” She boots the man. Come springtime, she revels in “the reassuring weight of the past on my shoulders.” Yet in hospice, she “repeatedly experience[s] the failure of my memories, the imperfection of memory itself.” When all else is gone, what else is there? We’d do well to remember that.

Tripier’s exacting prose captures the story of a woman locked in and looking back on life, but it also holds moments of sheer joy recognizable by any reader who’s creating or reliving memory. May those moments extend beyond the walls of a house into a fully-lived life. Level the rubble, indeed.

About the reviewer: Catherine Parnell is a writer, editor, educator, and the Director of Publicity for Arrowsmith Press. She is co-founder of MicroLit and serves on the board of Wrath-Bearing Tree. Her publications include the memoir The Kingdom of His Will, as well as stories, essays, and reviews and interviews in Reckon Review, Compulsive Reader, Five on the Fifth, LEON Literary Review, Cutleaf, Funicular, Litro, Heavy Feather Review, Mud Season Review, Emerge, Orca, West Trade Review, Tenderly, Cleaver, Free State Review, The Brooklyn Rail, The Rumpus, The Southampton Review, The Baltimore Review, and other literary magazines.