Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

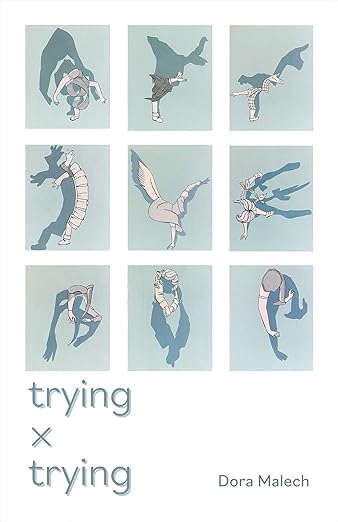

trying x trying

by Dora Malech

Carnegie Mellon University Press

Sept 2025, $20usd, 88 pages, ISBN: 978-0887487118

Dora Malech’s verse is a treat to read, melodious, euphonious, clever, and rife with delicious riddles, often ending in bon mots or wisdom, a breathtaking line or image. (She ends the poem “In Western Massachusetts” with “Wherever I look is looking away.” The poem “Abbr. Bestiary” ends, “The roar you hear is just eternity.” Stunning and thought-provoking.) Malech’s nimble facility with words is a thing to admire. Just take the start of the poem, “saw, circular”:

we serve

the swerve that one

good turndeserves. another

riven swivel,

pivot fodder.the whole flock

reverses charges,

calls collective.turn me

on to turn me

one again.

The internal rhyming – serve, swerve, deserve, reverse; riven swivel pivot – and the seeming effortlessness of “turn me on” becoming “turn me one,” and what one good turn deserves (“deserves another” – “deserves. another”) are sheer delight to read. And so it is throughout this collection. This circular poem ends on: “disavow each // season’s treason // as it reveals / the wheel.” Or take the description of her mother as a schoolgirl in the poem, “Confessional”: “a knock-kneed natural / heretic, pint-size apostate disguised / in pleated plaid.” Fun to say! Fun to read! The poem “verum factum” reads:

a flaw I follow seems

seam’s source suturedsoldered line of scar-shine’s

old itch good as knew

The paronomasia here and all over trying x trying is astounding, and the cryptic title – trying x trying – likewise highlights Malech’s elusive cleverness, her coy, seductive use of words, her dexterity with language. Dora Malech’s verse makes you think of an acrobat who makes it look so easy, flying through the air, swinging on the trapeze, gracefully contorting, spinning, landing in a seemingly single effort. And the title, trying x trying? There’s an exponential effect in lived time in which effort begets effort and challenges multiply, accelerate. “Trying” means to attempt, but it also signifies stressful, demanding, frustrating, and this is the picture of the world she paints, whether it’s in relation to child-rearing or being a citizen assaulted by the news. Against all the odds we try. The poem, “How to Make It” spells out the essential challenge:

All my friends are now at a distance,

overwhelmed with work and world and care,injustice, filled with fear of bills and illness,

running scared though going nowhere and so,of course, taking on more chores by other

names…

They’re all trying but it’s so trying. The “friends at a distance” is also a reference to the pandemic, which is a theme throughout (“Tried,” e.g.). The two short poems that open trying x trying are like a metaphorical precis of the entire collection. “Dream Recurring” reads:

All eyes turn doorward

toward me.This is History.

Where are you supposed to be?

What am I supposed to do with this life I find myself living? A constant question from the depths of consciousness, like those repeated dreams that always turn out to be one’s relationship to authority. Recurring, elemental.

“Attempted Haiku,” meanwhile, reads:

The nation is holding its breath…

NYT, January 17, 2021

Breath, yes, but what else

can we hold? Water, space for,

accountable, fire?

The epigraph from the NY Times refers to the aftermath of Trump’s attempted coup, the uncertainty about the way forward. Bottom line: we’re all left holding the bag, whether it’s the political reality or just our own lived lives. In “Unaccompanied Minor” she tells us her feet “can reach / the pedals now, // but still I go nowhere,” a Sisyphean image regarding the “unsung song / about the road.”

For women, pregnancy is trying. You hear about couples who are “trying,” meaning to have a baby. Malech writes about pregnancy, miscarriage, birth, child-rearing. There’s the cleverly titled “Rearview Mère,” Malech’s signature wordplay at work, “Gwass,” a poem about her daughter beginning to speak words (and words are Malech’s métier, remember), “Ablation,” about lactation and nursing an infant, “Last Ultrasound” (“The wand warms me while your pieces swim / into focus.”). “For My Friend Who Is Tired of Children in Poems” may or may not reveal the poet’s own mind. (“I also tire of children in poems and of children / off the page as well,” she begins.) The poem ends:

These are just words. Blame me, but it’s in my blood

to love this way. I make a study of it.

Together, let’s be sick of the sweetness of this world.

So much of it isn’t so sweet, as we’re reminded in the daily bombardment of the news. The prose poem “The News” begins: “Now’s news begins with babies on the way.” In “The Forecast,” which also features pregnancy (“My unborn / baby basks in her microclimate, oblivious / to other weather, other worlds.”), Malech writes: “All day / yesterday I tried to tune out the news, or rather / to consume without being consumed.” It’s always one outrage after the other, isn’t it?

The news is full of the injustices of the world. The poem “Perfect for those corrections in a hurry!” takes its title from the slogan for products like Wite-Out and correction tape, but chillingly it makes one think of the way the Trump administration is hellbent on wiping out history, erasing DEI. The poem ends:

We are our own worst

witness, witless, as if

checking the closet for ghosts—

see, honey, I don’t see anything.

Apostrophe as possession, omission,

address (with roots in a turning

away): can t. As in, what we don’t

know hurt us. As in, I breathe.

The last line with its grim reference to Eric Garner and so many of the Black Lives Matter victims is made so much more poignant by that blank space where “can’t ” should be.

“Monumental Life Building” is a poem that takes off from a monolithic insurance company building in midtown Baltimore, but it ends in the Wyman Park Dell across from the Baltimore Museum of Art, where a bare plinth stands that once showcased a double equestrian statue of the Confederate generals, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. The statue was removed in 2017, after the white supremacist Dylann Roof killed nine Black people in a Charleston, SC church where they were engaged in Bible study, two years before. The bare plinth “shrugs perpetual / disavowal of past purposes….”

Language, indeed, is Malech’s element. Words, punctuation, spelling. The poem “Y,” after the Venezuelan poet Vicente Gerbasi (four poems in trying x trying are an homage to Gerbasi, “Y,” “At Times,” “Cuando, cuando,” and “Arrangement”) is another dazzling display of Malech’s dexterity with language. “Venimos de la noche y hacia la noche vamos,” she begins the poem, echoing Gerbasi’s “Canto I.”

Our journey hangs on a letter’s hinge.

It sentences its sentence to itself, a life

in prism through which all our minor

refractions flash back and back.

Its form bears, but barely, the weight

of the losses slung across its shoulders.

You actually see that letter –sentenced as it is to a “life in prism” – just as you see it in “The letter aims like a slingshot,” the written figure’s forked prongs, and in the poem’s vivid ending:

The letter flicks

its forked tongue. As it advances,

it holds its arms up high, gesturing

through emptiness as if across

a crowded room. It is a wishbone

wondering which way to break.

Silt stirs at the confluence of its rivers.

“Niqqud” is a poem about the system of vowel diacritical marks used in Hebrew orthography to indicate vowel sounds that are omitted in modern Hebrew texts. “Nesting” begins with an observation about phonemes, the sounds of words, and we see this throughout her work, the musicality of language. The poem “whether,” which plays on the similar-sounding “weather” (a powerful metaphorical element of her poetry, as we’ve already seen in “The Forecast”) displays Malech’s playfulness with language and word sounds:

a future read aloud

spells out a couldwithout you

in your element

leaves cold

as our orand even

with remains

a wintery mix assleet stung one

unsettles gonepotential ever forecast

in a chance of cloud

“Aloud,” and “cloud” and the almost “could” followed closely by “cold” – the unsettling stinging sleet of the wintery mix – the words fill your mouth like some sort of workout. It’s truly another fun poem to say aloud, to taste the words.

So how does one balance effort and obstacle, and what are the inherent warnings? If this is the final impact of trying x trying (and I’m not saying it is! Not putting words into her or anybody else’s mouth), Dora Malech doesn’t provide answers to these questions that she isn’t even asking. But in the end she seems to urge a sort of prudence and restraint, acceptance. In “Secret Song” she writes:

The buttercups’

and dandelions’

yellow lights blink

on with the season.

Little hypocrites,

my hearts, who

want a wild life

the color of caution.

About the reviewer: Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for Brick House Books in Baltimore and Reviews Editor for The Adirondack Review. His most recent releases are Sparring Partners from Mooonstone Press, Ugler Lee from Kelsay Books, Catastroika from Apprentice House, Presto from Bamboo Dart Press, See What I Mean? from Kelsay Books, The Trapeze of Your Flesh from Blazevox Books, and just out, The Tao According to Calvin Coolidge, published by Kelsay Books.