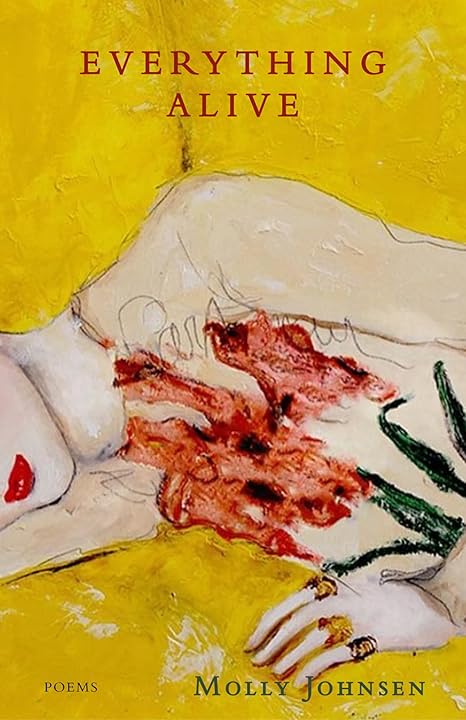

Molly Johnsen’s debut book, Everything Alive, is a poignant reflection of love, grief, and the fragility of life. Written after a devastating car accident, Johnsen’s poems urge the reader to accompany her as she reels from physical, mental, and emotional impacts and tries to adjust to her drastically shifted world. Although her poems center on painful topics, the book strikes a balance between Johnsen’s grief over what she lost and her love of those who remain.

Molly Johnsen’s debut book, Everything Alive, is a poignant reflection of love, grief, and the fragility of life. Written after a devastating car accident, Johnsen’s poems urge the reader to accompany her as she reels from physical, mental, and emotional impacts and tries to adjust to her drastically shifted world. Although her poems center on painful topics, the book strikes a balance between Johnsen’s grief over what she lost and her love of those who remain.

Congratulations on your debut book, Everything Alive! How did you first get into writing poetry?

Thank you! I’ve always had poetry in me. I remember the first poem I ever wrote. I was probably around four. It goes, “A tree is a tree/A tree is not you or me/A tree is a tree.” I think the joy those words brought me—that feeling of stringing them together and reciting them aloud—is proof that the love is innate. Now, as a parent to young children, I see my young self trying to make sense of the world in that poem. I’m saying, “I have no idea who I am, or who you are, but I know what a tree is.” Those juxtapositions are happening all the time in young minds, and mine used poetry as a vessel.

Your bio mentions that you teach middle schoolers. Has that influenced your writing style or your outlook on life?

Oh, what a great question. I think of myself as so many different people, and Teacher Molly is completely separate from Poet Molly. That said, the yearning, raw emotion and vulnerability and hurt and jubilation that I see in my students is both inspiring and inescapable. By getting to know each student as a person who is in the midst of figuring out how to be autonomous, I have the chance to regularly engage with a spectrum of human emotion that, whether Poet Molly likes it or not, stays with me. My students inspire me to find solace in figuring out who I am, rather than seeking certainty that I already have the answer.

Your book is split into five sections. How is each section defined? How did you decide the order of poems?

Your book is split into five sections. How is each section defined? How did you decide the order of poems?

This took me so many attempts, and I’m still not certain I got it right. I’ve always known that section II, a lyric essay written as a direct address to my Epilepsy, had to come after some early poetry about the aftermath of my physical trauma. This was a practical decision, so the reader would have context for all of the epilepsy poems that followed.

As far as the other sections, some of it is merely chronological. My relationship with loved ones, my healing, my physical location. After that, I worked on layering themes and emotion. Section I sets up all of the key relationships in the book. Once that felt right, I was able to move into a less urgent section about processing and understanding my needs. Section IV feels like less of a yearning and more about finding. Putting language to what I want—or what I don’t. And then the final section is, hopefully, a culmination. I wanted it to have momentum toward the sense of finality I seek in so many poems. The order of the work has changed many times, but “Everything Alive” always came last. I knew when I wrote that poem that everything had to lead up to it.

You use dark humor to filter some of the more difficult subjects in your poems. Why do you find it important to use humor in your poems?

I think it’s just who I am. My therapist has taught me that I have trouble sitting with my own emotions. Jokes are meant to remove some of the pain from the situation. But I also believe they are humanizing, reassuring, and, hopefully, a way for me to connect with my reader. Here, I try to say, laugh with me for a moment. It’s okay to laugh.

There are also points in the work that I didn’t realize were funny until I read them aloud to an audience. Figuring that out through others is such a beautiful thing about what poetry does. I learn about myself and my work through those who process it. What a gift.

Your poems reflect such a deep and personal part of yourself. Has writing poetry helped you process your emotions and memories?

No question. I didn’t develop a regular poetry practice until after I was hit by a car in my late twenties. While I had no idea at the time, it’s clear to me now that, like the little girl who wrote the tree poem, I was putting words to something huge, to newfound knowledge of what it feels like to teeter at the edge of life and come back. Poems like “Follow-Up With the Orthopedist” speak to my urge to change the narrative. To take control, even if I was only doing it in my own mind. I can step back now and look at the work and think, “Oh, so this is how I feel.” Maybe I can’t sit with my emotions, but I can rework a poem twelve times until it feels real.

A lot of your poems mention your car accident. How did the accident change the course of your life?

I wrote a narrative essay awhile back that describes the accident as a thick, black line at the center of my memory. A before and after. I know this is common with traumatic incidents, and I’m now living in the “after” part of my life. I wish I could say that I don’t take a second for granted, that I’m thankful for every day, but that’s not my experience. Instead, I think I’m more afraid. It took me a long time to come out of my own mind and realize how traumatized my parents were. Now that I have children, I can’t imagine what my parents went through during the time I was hospitalized. My poem “We Call it Beautiful” is about all the fear I feel. The brown specks on a banana can turn into a meditation on all the ways someone I love might die. The fear is hard, but it wouldn’t exist without tremendous gratitude: for my loved ones, and for my own body.

In your poem “Epilepsy,” you address your epilepsy as an entirely separate entity from yourself: “You leave me out. I only have what I’m told and / what you cackle before blacking me out” (25). What inspired you to confront it in such a way?

I’ve always thought of my epilepsy as something separate from me, and I’ve always personified it for myself. In writing directly to my disability, I found solace. Instead of, “Why do I have seizures?” I got to ask, “Why do you make me seize?” I’m still me with that phrasing, rather than a disabled person. The irony, of course, is that the latter is who I am. Learning to claim and accept my own disability remains a work in progress. And epilepsy is tricky because it hides. When I was pregnant, strangers held doors for me. They carried groceries to my car. My condition was visible. An invisible disability is hard for me to grab hold of. My trauma did not make me Type A, but I am, and I don’t feel comfortable with a lack of control. If I can harness something untamed in my writing, I’m going to try.

While many of your poems focus on working through your personal grief and trauma, the rest of them read like love letters to your family and friends. When you were writing, did the book’s balance of love and despair happen naturally or was it intentional?

The most beautiful surprise that came from this collection is early readers’ ability to see so much love in it. I was afraid that wouldn’t come through—that I was focusing too much on death and trauma and grief. So, no, it wasn’t intentional, but I’m so grateful for the balance. I think it’s natural that, in exploring the heaviness, in aching for life, I found so much love. You can’t feel one without the other.

Many of the aforementioned love letters include poems written to your unborn children. Did you write those poems before you had kids? Why did you choose to end your book with your son’s birth?

I wrote the first draft of every poem in the collection before I had children. One of the very first questions I asked my medical team while I was hospitalized was whether I’d be able to have children. This uncertainty is a theme throughout the collection, obviously and, when I first wrote the poem “Everything Alive,” I still didn’t know the answer. In retrospect, the poem is a kind of incantation. I was trying to will a baby into being.

In the first draft, I didn’t have the word “son” in there at all. I called my future baby “it.” One of the notes I got back from a friend who read an early draft was not to end on the word “it.” A long time later, when I began editing in earnest, I’d had a child and realized I could give him a pronoun and include the triumph of motherhood right at the end. While the poem may not stand alone well, my hope is that, once someone has read the preceding poems, they’ll realize why that one has to be the end.

If you were to write another book, would you center similar themes and events as in Everything Alive, or would you go in a completely different direction?

I once complained to my M.F.A. thesis advisor, Chris Kennedy, that I was sick of writing poems about myself but felt unable to do anything else. He told me something along the lines of, “Everyone writes the book about themselves, and then they can move on.” I found that reassuring. This collection feels so contained to me, so complete in its subject, that I’m hoping it’s behind me.

Most of my favorite poems are meditations on human nature rather than personal narratives. The ability to move beyond the personal—at least explicitly—is, in my opinion, a sign of poetic brilliance. Who knows if I’ll get there, but it’s good to have a goal.

Molly Johnsen is a Vermont-based writer and teacher. Her work has appeared in the Nashville Review, Indiana Review, Cider Press Review, and others. A previous version of Everything Alive was selected as a semi-finalist for the Black Lawrence Press St. Lawrence Book Award. She holds an MFA from Syracuse University.

About the interviewer: Deanna Perlov is a student at Pomona College, where she studies history, music, and religious studies. She is drawn to books that combine art and information.