Reviewed by Emma Desserault

Reviewed by Emma Desserault

Daphne

by Kristen Case

Tupelo Press

ISBN-13: 9781961209206, Paperback, 82 pages, June 2025

Blood Feather

Blood Feather

by Karla Kelsey

Tupelo Press

October 2020, 112 pages, ISBN-13: 978-1946482419

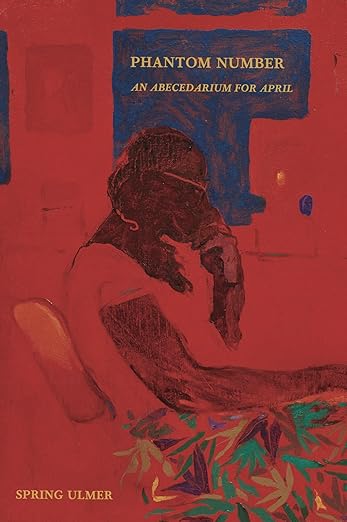

Phantom Number: An Abecedarium for April

Phantom Number: An Abecedarium for April

by Spring Ulmer

Tupelo Press

February 2025, 82 pages, ISBN-13: 978-1961209176

Daphne by Kristen Case, Blood Feather by Karla Kelsey, and Phantom Number: An Abecedarium for April by Spring Ulmer, though radically different in many ways, share concerns with language, violence, gender, and more, as well as similarities in their formal elements. Daphne, by Kristen Case, explores the nature of violence, both as an enabler and a disruptor. Through the voices of three women, Blood Feather by Karla Kelsey wrestles with feminism in our current world and in our history. Finally, Phantom Number: An Abecedarium for April by Spring Ulmer examines history, philosophy, racism, activism, motherhood, language, and friendship, framed through the loss of a woman named April. Each piece is entirely its own; however, there is much to be gleaned from examining these works together and analyzing how reading them together might inform a greater understanding of the topics presented in these works.

Daphne, Blood Feather, and Phantom Number share many thematic elements, including their exploration of violence, gender, the body, and their interrogation of language. In terms of violence, gender, and the body, Daphne explores how these thematic elements are intertwined. It is largely through the Greek myth of Daphne, a nymph who turned into a tree to escape the sexual advances of the God Apollo, that Daphne frames itself. Daphne’s story acts as the perfect example of how violence, gender, sexuality, and the body are interconnected. Case unpacks the paradox of the myth of Daphne, as her transformation is both an escape and an annihilation. In Blood Feather, female bodies are described as almost mythic (as seen through the examples of Maria Tallchief, the Firebird, and Penelope). Kelsey’s references to ballet, war, and myth suggest that women are performers, their bodies objects for possession. In Phantom Number, Ulmer directly links racism, loss, police violence, and personal grief (April’s death) with structural and societal oppression. Ulmer also explores how racialized and gendered bodies can be sites of disempowerment. Though each text deals with the themes of violence, gender, and the body in varying ways, there is a thread connecting all three works: that violence, gender, and the body are inherently linked.

Each of the texts also explores the interrogation and violence of language. In Daphne, language is presented as violent, erotic, and philosophical. The text plays with and warps definitions (this is especially evident in the analysis of the words “ravish” and “tonic”) to reveal embedded power structures within the way we use language. Blood Feather uses phonetic play such as Adam/atom, multilingual references, and fluidity to add depth, emotional resonance, and irony to the poems. Phantom Number explores how language is commodified under capitalism. Words both mark and erase, hide and showcase. Phantom Number reveals to us that small shifts in language, such as from “battle” to “massacre,” can have drastic impacts on our understanding and our history.

Each of these bodies of work is formally and structurally different, yet each manipulates language and form in a way that challenges expectation and reveals deeper meanings. In Daphne, blank space, coded symbols (EONEONE…), and typographical breakage act as violence and refuge. Additionally, many of the pieces are structured like academic papers. Case weaponizes academic language to garner authority and establish truth, while also mocking the inherently patriarchal academic tone often used in this kind of writing. Continuous lines without punctuation and parts bleeding into each other are distinct aspects of the structure of Blood Feather, mirroring the poem’s content of fluid identity and historical layering. Phantom Number uses the Abecedarian form (poems in alphabetical order), yet Ulmer takes the abecedarian and flips it on its head. The essence of the abecedarian is still intact, but formally, it is completely turned around. Additionally, the collection’s use of fragmentation reflects grief’s interruptions and incomplete nature. This is especially evident in the final line of the collection, ending at the beginning of the alphabet with the letter “a.”

Each of these texts is also teeming with intertextual references and quotations. In Daphne, Case invokes Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Wyatt’s sonnet “Whoso List to Hunt,” among others. In Daphne, the academic and lyrical voices blend together, creating a strong critique of patriarchal epistemology. Leo Tolstoy, Simone De Beauvoir, Anne Radcliffe, and Vladimir Nabokov are among the authors explored in In Blood Feather. Finally, in Phantom Number, poets, philosophers, and activists are given voices. Ulmer is careful in her choice of intertexts, giving voice to many whose voices were not heard, or were heard too late.

Where these texts differ greatly is in their voice and persona. Daphne oscillates between the philosophical, poetic, and confessional first-person, even sometimes destabilizing its own authority with statements like “I want to suggest.” Blood Feather shifts through different female personas, while referencing themselves as “our heroine,” highlighting the collective female experience that the poems aim to feature. Phantom Number incorporates direct elegiac address to April, the second-person, and systemic critique, creating a sense of intimacy and collective mourning. Though each author tackles the poetic voice differently, each accomplishes what they set out to do: to explore, identify, and illuminate.

The reading experience of each of the texts is also vastly different. Daphne demands intellectual engagement, with its use of footnotes and intertexts, forcing the reader to confront the violence embedded within language and knowledge. Blood Feather’s immersive poetic flow without punctuation evokes the relentless accumulation of language, history, violence, and mythology. In Blood Feather, one moment leads into another, one perspective into another, and so on. Phantom Number’s brevity and abecedarian sequence intensify the grief it seeks to explore. Each text asks something different of the reader and in different ways, but what remains the same is the command of the reader’s attention, understanding, and empathy.

Daphne by Kristen Case, Blood Feather by Karla Kelsey, and Phantom Number: An Abecedarium for April by Spring Ulmer share a commitment to interrogating violence through radical form, exploring how language, gender, racism, and more are informed by one another, and how each is embedded within every aspect of our society. Despite their shared aspects, each work is not without its own unique aspects. Daphne acts as a philosophical-poetic treatise, Blood Feather a mytho-poetic tapestry, and Phantom Number as an elegiac social document. Works like these need not only to be read, but deeply understood, if there is any hope to move forward.

About the reviewer: Emma Desserault is a senior at Tufts University studying English and Film and Media Studies. Originally from Ketchum, Idaho, Emma is passionate about helping readers find stories that inspire empathy, connection, and a lifelong love of reading.