By Daniel Garrett

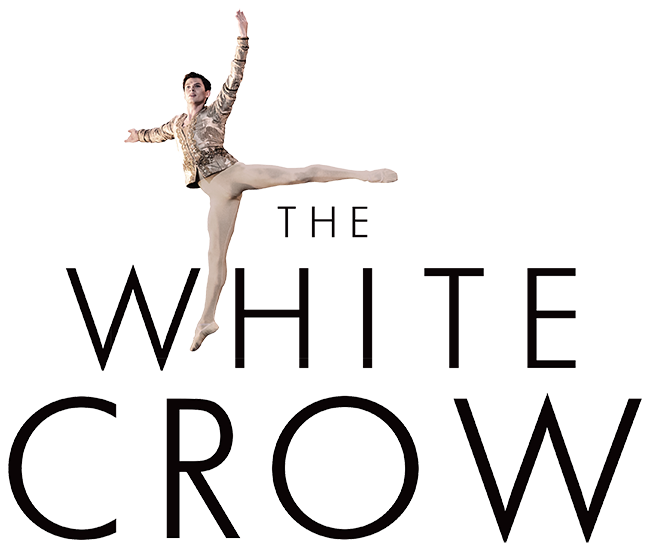

By Daniel GarrettBallet is dance—it is the fine symbolic movement of sensitive, sensual people. Born during the 15th century Italian Renaissance, the time of rebirth of classical values in literature, the arts, and philosophy that inspired people and practitioners in different fields, including architecture and painting; and ballet was later refined by French and the Russian practitioners. The Italian ballet was known for a sense of the noble conveyed through expressive power, narration, spectacle, and virtuosity, and a variety of cities nourished the dance, such as Florence, Milan, Venice; and the French gave to the form new techniques, a refinement of steps, an ideal of fluid grace, whereas the Russians drew attention to drama, to interpretation articulated in forceful movement. Three of the most significant dancers of all time have been Russian: Vaslav Nijinsky, Rudolf Nureyev, and Mikhail Baryshnikov. The White Crow (2018), a dramatic film taking Rudolf Nureyev as the central character, is a smart, engaging, attractive work, moving between the youthful subject’s past and present; and it is a film that makes clear that being creative is an assertion of freedom. Rudolf Nureyev spoke of feeling as if he had to make his own way, as if the path had not been prepared for him—and he took pride in his own hard work.

Is destiny assured? Would he, Nureyev, choose tradition or change? Could this Russian boy speak to others? Would his life mean anything to the world? The White Crow (2018), directed by Ralph Fiennes, is an interesting film about Rudolf Nureyev (1938 – 1993), a dancer, a man capable of astonishing leaps, who began his career at the Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet and the Kirov Ballet, before leaving Russia for Paris, London, New York and international travels, and forming a luminous and powerful bond with prima ballerina assoluta Margot Fonteyn, the best of the best, with whom Nureyev as Albrecht danced in Giselle (1962), the two receiving twenty-three curtain calls, and Marguerite and Armand (1963), and Swan Lake (1964), with their last ballet together being Romeo and Juliet (1979); and Nureyev collaborated with distinguished artists around the world, ending his career with the Paris Opera Ballet. The film, written by playwright and theatre director David Rippon Hare, the author of Plenty (1978) and screenwriter for The Hours (2002), is based on the first 141 pages of Julie Kavanagh’s comprehensive and intelligent book Nureyev: The Life (Pantheon Books, 2007), with production design by Anne Seibel, and costumes by Madeline Fontaine, and it was photographed by Mike Eley, edited by Barney Pilling and scored by Ilan Eshkeri. The film’s dance advisor was Johan Kobborg. In The White Crow, we see some of Nureyev’s life, his youth and his training in Russia, and his early triumph in Paris: the past is the dancer’s birth on a Trans-Siberian train, his boyhood, and his performance preparations; and the present is his visit to Paris, a personal and professional opportunity for advanced discoveries and public appreciation. In The White Crow, directed by Ralph Fiennes, the dancer and choreographer Rudolf Khametovich Nureyev, here played by Ukrainian dancer Oleg Ivenko as a young man and by Maksimilian (Maximilian) Grigoriyev as a boy, there is black-and-white footage of a woman, Farida Nureyev (Ravshana Kurkova) giving birth to a baby, to Rudolf, Rudik, Rudi, on a train; and, a few years later, the boy Rudik watches other children play together. In the town of Ufa, in the republic of Bashkir, Rudik’s father Hamet returns, embraces his wife, and looks around—and he sees his son Rudik, whose mother Farida encourages to greet his father Hamet, who hugs him. (Rudik’s sisters observe—he is the only son, the fourth child.) There is an excursion in the forest with Rudik and his father, a hunting trip; and his father lights a fire, and tells him to wait there, and his father is gone a long time, leaving Rudik in the cold. There is ambiguity—is a lesson being taught; or is this a kind of abandonment, or indifference? Does Rudik’s distance from his father motivate him to seek the friendship and love of other men?

Rudik dances as a boy, and wants to become a professional—and he travels to Leningrad to study. Color enters Rudik’s life when he moves closer to dance. Rudi (Oleg Ivenko) arrives from Ufa, his hometown, to study at the Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet in Leningrad, living in a dormitory; and when Rudi becomes frustrated with his challenging and impersonal teacher Valentin Ivanovich Shelkov (Radoslav Milenkovic), Rudi enters another teacher’s class, that of Alexander Pushkin (Ralph Fiennes), who gives him simple instructions and conveys a vision of narrative dancing—and does not humiliate the young dancer. Rudi practices. He studies sculpture, observing the look and positioning of the human body. Rudi asks his teacher, Pushkin (Fiennes), if Rudi pleases Pushkin; and the teacher says Rudi does not displease him—and teaches him more, telling Rudi that there is a logic to steps, a larger story being told. Pushkin’s method is to encourage the students to become more aware of their own movements, to discern and correct their own errors. “A serene, almost hieratic man, the maestro was soft-spoken and direct, not given to elaborate verbal instructions, although pupils learned to tell if anything displeased him by the blush that slowly crept up from his neck,” wrote Julie Kavanagh in Nureyev: The Life (page 41). Rudi is developing discipline. Whether onstage or at the barre, whether practicing alone or bringing an audience to a boil, this Nureyev can be seen whole, in leaps and bounds, with no editor’s sleight of hand As any Cyd Charisse fan will confirm, that honesty matters more than acting,” noted New Yorker critic Anthony Lane (April 26, 2019).

Ralph Fiennes, an actor and director, said he was drawn to Nureyev’s ferocious sense of density: “What struck me was the sheer presentational, charismatic, sexual force of him as a spirit onstage,” Fiennes told Matt Donnelly of Variety magazine (“Ralph Fiennes Examines Rudolf Nureyev’s Complicated Life,” April 18, 2019). Fiennes, who had starred in Wuthering Heights (1992), Schindler’s List (1993), Quiz Show (1994) and The English Patient (1996) after training at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and performing with the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company, directed the films Coriolanus (2011) and The Invisible Woman (2013), before The White Crow (2018). His range as an actor is impressive and his taste as a director is impeccable. Fiennes can appear sensitive or extremely cold, moral or savage. I still relish his work in Strange Days (1995), Oscar and Lucinda (1997 and The Constant Gardener (2005)—and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). Fiennes performed in a film with a great Russian subject, Onegin (1999), about a nobleman whom a young woman becomes infatuated with, a story based on nineteenth-century writer Alexander Pushkin’s verse novel examining idealism’s relation to social life, Eugene Onegin (1833), directed by the actor’s sister Martha Fiennes. Ralph Fiennes, someone who had liked David Lean’s film Doctor Zhivago (1965) and Anton Chekhov and was touched by the openness of the Russian people, found the sensibility of Onegin one that resonated. Ralph Fiennes is, and understands what it means to be, an artist.

Ballet is dance—it is delicate movements set to music, illustrating a tale: it is adagio (slow movements) and allegro (rapid movements) and arabesque (the body’s weight on one leg, with the other leg aloft, backward) and changement (change of feet) and fifth position (the heel of one foot against the toe of another, the two feet close, turned out) and plie (bending of a standing leg) and sauté (jump); and it is the life, the creative work, Rudolf Nureyev wanted. In The White Crow, the dance teacher Alexander Ivanovich Pushkin (Fiennes) thinks that Rudi neglects to eat and has his wife Xenia Jurgenson (Chulpan Khamatova), the elegant daughter of a St. Petersburg couturier, bring Rudi food, French onion soup. The Pushkins were known to nurture students—to encourage their artistic and personal growth. Rudi practices more than the other students—to make up for lost time (they started dancing before he did). Rudi has been regularly visiting the Hermitage, looking at art. In Leningrad, Rudi visits other young people, a family and friends, who eat, drink, and discuss culture. The other young people have a sense of optimism about the Russian future. Rudi also visits the home of the Pushkins, his teacher Alexander and his wife Xenia, for dinner; and Alexander Pushkin, again, talks about the importance of story in dance. Unfortunately, Rudi falls, injures himself; and he goes to the Pushkin household to recover. An affair with Pushkin’s wife begins—one she initiates. Xenia—who was near the end of her own dance career—would develop a special, even obsessional, devotion to Rudolf Nureyev (and, in time, Rudi could be rude to her and would become wary of voracious older women). When Rudi is able to dance, Teja Kremke (Louis Hofmann) photographs him, and review of the film is an instructional tool, as they watch and discuss what Rudi can improve. Teja sees how Rudi appreciates Teja’s knowledge of the larger world. Teja and Rudi go to bed (Nureyev said Teja taught him the art of male love); and Teja asks why Rudi is still with the Pushkins, in their home. “You can’t resist foreigners,” says Teja, adding, “You dream of a world that isn’t this one.”

Rudi goes to Moscow to complain to the ministry of culture about a work assignment Rudi receives to Ufa, which he thinks will interrupt his career. Rudi is told the Soviet people paid for his studies, and he owes them something; but, then, an older woman dancer offers him a partnership at the Kirov (she will make him seem more talented; and he will make her seem younger). Rudi accepts—wanting to dance, wanting to be seen to dance. He would bring forth a new legend.

Rudolf Nureyev was a bridge between traditions—between classical dance and modern dance, and between fine art and the popular mediums of film and television. Nureyev would be the bridge, too, between Nijinsky and Baryshnikov. Vaslav Nijinsky (1889 – 1950), the well-schooled son of revered dancers, a legend when young, and known for beauty and strength, performed in Giselle, Swan Lake, and Sleeping Beauty at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, before becoming part of the Ballet Russes of Serge Diaghilev, choreographed by Michel Fokine in works such as Petrushka and Schéhérazade, as well as appearing in Nijinsky’s own works, L’Après-midi d’un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun) and Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring). Nijinsky, who thought the whole body should dance, would suffer schizophrenia and be committed to a mental institution. Nureyev would acknowledge Nijinsky’s legacy by dancing some of his famous roles—and Nureyev would demonstrate for Baryshnikov the immense possibilities for a Russian artist in Europe and America. Baryshnikov, born in Latvia in 1948, impressed those in his Riga ballet school, and studied in Leningrad with Alexander Pushkin, and joined the Kirov Ballet as an agile soloist and became a premier dancer performing, and sustaining significant leaps, in original ballets—Gorianka (1968) and Vestris (1969)—but in Russia, Baryshnikov, known for his mastery of difficult steps, could not perform (could not be challenged or refreshed by) contemporary ballets by foreign choreographers, a great limitation to him—and while touring Toronto in 1974, he defected. Baryshnikov would join the American Ballet Theatre and dance with the New York City Ballet, before creating his own White Oak Dance Project and Baryshnikov Arts Center. He became an exemplar of dance.

The feature film The White Crow, about one of the most charismatic and powerful dancers of all time, Rudolf Nureyev, shows us a young man looking out of a window onto a new world, France—a life full of color, full of liberty—different from his childhood, different from his life in Russia. Rudolf Nureyev had carried within a vision of freedom, of creativity: he wanted to learn different traditions and techniques; he had no terror of transgression, and exuded desire, liberty, will, looking for what will gratify. Rudi (Oleg Ivenko) arrives in Paris in 1961; and he is welcomed with the other members of the celebrated Russian troupe, the Kirov Ballet, once known as the Imperial Russian Ballet (now known as the Mariinsky Ballet). Rudi looks sensitive, and sensual—he looks hungry. He goes for a walk in the city, Russian agents following him. Rudi sits in a café, and is interested in getting a toy train. He is a young man, but he relishes the long desired boyish toy. In the Palais Garnier in Paris, Nureyev is not scheduled for a first night performance, a disappointment, but he is confident of his eventual fame. Nureyev walks to a museum, the Louvre, to await its opening to see Theodore Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa, a turbulent painting, which he studies. The Russians have been warned against fraternization, against being compromised. However, Rudi makes an effort to talk to the French dancers—he has seen them in magazines, Pierre Lecotte (Raphael Personnaz) and Claire Motte (Calypso Volois). The Russian troupe practices, observed by interested French dancers. They are all beautiful and talented young people (there is an erotic frisson just having them in the same room, no doubt frightening to authorities who want to maintain control). One of the French male dancers says that the French invented the ballet (King Louis XIV in France in 1661 began the first ballet school), but that the Russians give it something unique: and, Rudi has spirit and style, a way of taking the stage.

Why did Ralph Fiennes choose Oleg Ivenko to be his Nureyev? “I was looking for a number of things which are hard to describe: a quality of passionate modesty and of artistic hunger, a quality of impatience, and certainly a quality of arrogance or sense of destiny,” Fiennes told Galina Stolyarova of the Moscow Times (July 6, 2019). In The White Crow, before Rudi (Oleg Ivenko) is to dance in Paris in “Kingdom of the Shades” from Marius Petipa’s four-act La Bayadère, a story of a temple dancer who is loved by a warrior, Rudi prepares to go on the stage, and he recalls his childhood, his mother, and he performs: Nureyev (Ivenko) dazzles the audience—there are cheers, and shouts of bravo. Rudi, after his well-received performance, meets Clara Saint (Adèle Exarchopoulos), a sophisticated young woman, the daughter of a Chilean poet; and Rudi goes to dinner with her, and the French dancers, and his young male chaperone—his friend and roommate, the much admired Yuri Soloviev (Sergei Polunin), known for his exacting technique; but the film, wrote Christy Lemire, “wastes the prodigious talents of the great Sergei Polunin—who’s been compared to Nureyev—in a minuscule supporting role as Nureyev’s fellow company member and roommate on the road” (RogerEbert.com, April 26, 2019). Rudi wants to see modern paintings, that of Picasso and Matisse. The French dancer—Pierre (Raphael Personnaz)—says that The Raft of the Medusa is beauty made out of ugliness.

Clara Saint (Adèle Exarchopoulos) has lost a boyfriend, Andre Malraux’s son Vincent, in an accident, she tells Rudi, and she found Rudi’s performance transcendent. Rudi tells her that she must have a purpose in life; and he tells her the story about seeing an opera when he was six years old, that it inspired him, who was called a white crow (someone unusual, an outsider). Rudi shops for a toy train with Clara; and he is angry to be offered the Trans-Siberian Express, possibly because it is a train that he is too familiar with (or it’s an adequate representation of the real train). Rudi goes to a nightclub with Clara, and sees modern burlesque—there is, of course, an air of liberty. Rudi visits with friends a beautiful, stained-glass French chapel with intricate carpentry. Rudi says that he would like to live there (obviously surrounded by beauty, by something revered)—and Pierre says that it is not easy to live in a church (to live by piety, by rules). When Rudi is out late, he is reprimanded by Vitaly Strizhevsky (Aleksey Morozov), a dance troupe official who is also a state security agent; Rudi is warned, and asked about Clara’s wealth. The Russians fear Rudi will be seduced by western customs and values. Vitaly tells Rudi that this could be his last trip, if charges are brought against him. In a Russian restaurant with Clara, Rudi does not want sauce on his steak but does not want to talk to the waiter. Rudi is afraid of the waiter, whom he supposes sees that he is just a poor Russian, but Rudi expresses anger to Clara, who respects him and wants him to tell the waiter what he wants. (Rudi had been dismissive of a ballet master in Leningrad—Sergeyev—who talked while Rudi was rehearsing.) Rudi is both arrogant and insecure.

When it is time to leave, at the Paris airport, Le Bourget, Pierre gives Rudi a parting gift; and, suddenly, Rudi is told by Russian officials that Rudi is to go the Moscow, not London, for a gala for Khrushchev—then, that his mother is ill. Both seem implausible, mere subterfuges, to prevent Rudi’s transgressions, his defection. Rudi refuses to go to Moscow; he wants to go on to London with the troupe. He realizes they are trying to control and contain him. He knows they have done that to other dancers—and he fears prison. He asks Pierre to stay with him in the airport. Pierre has someone call Clara, who arrives, and offers Rudi help—Rudi, then, asks French officials for political asylum, to remain in France. (Once he defected, Russian officials at the highest levels discussed the possibility of tracking down Nureyev, of killing or maiming him; and his family and friends were interrogated and harassed.) Rudolf Nureyev joined the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas, founded by choreographer George de Cuevas, the day after Nureyev asked for, and received, asylum in France; and Nureyev soon met the impressive Erik Bruhn, a principal dancer with the Royal Danish Ballet, from whom Nureyev learned—and whom he loved. Nureyev would perform Giselle with Margot Fonteyn and the Royal Ballet in Covent Garden in 1962, forming a legendary partnership, and in 1963 Nureyev danced with ballet companies on three continents; and, eventually, he would perform the demanding works of a variety of choreographers, including Maurice Béjart, George Balanchine, and Martha Graham. During his career, he returned to the great works of Russian ballet. Nureyev appeared on television and in many magazines and newspapers—and in film. “Intelligent and illogical, beautiful and erratic, Exposed is a provocative, jet-setter’s visit to the worlds of high fashion and international terrorism,” wrote Variety magazine staff of James Toback’s film Exposed (1983), starring Nastassja Kinski and Rudolf Nureyev, but “Kinski and Nureyev lead the way in ably fleshing out characters who are meant to remain mysterious” (December 31, 1982). And, in 1983 he became the dance director of the Paris Opera Ballet; and in 1989 he danced at the Kirov Theatre in Leningrad, a visit to Russia made so that he could visit his very ill mother. Nureyev, in his last years, did not dance his famous roles as well as he did once—but new roles were created for him that took his age and mature acting ability into account and he was known to be effective in them. Nureyev choreographed La Bayadère—in which he had first appeared in 1961 before a French audience—for the Paris Opera Ballet, and his last public appearance was October 8, 1992, at its premiere: “His Bayadère had been a personal triumph—the apotheosis of a thirty-year mission to bring Petipa’s unknown classics to the West. Brilliantly paced, its contrasts silent movie mime and rhapsodic love duets with formulaic divertissements of classroom steps interspersed with vibrant character dances,” wrote Julie Kavanagh in Nureyev: The Life (Pantheon, 2007; page 685).

The adventurous and well-endowed Rudolf Nureyev had done inspired and inspiring work. Nureyev may have had as many lovers as dance tights; he had been quite promiscuous (and was sometimes an indifferent or passive lover, according to Julie Kavanagh’s sublimely gossipy book)—was his pursuit of sex a quest for pleasure or a perpetual refutation of repression?—and he died of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) on January 6, 1993. Nureyev is featured in several biographical and performance documentaries, including Nureyev: A Portrait (1993) by Patricia Foy; and Rudolf Nureyev: Island of His Dreams (2016) by Yevgeniva Tirdatova, about Nureyev’s visits to Turkey; and Nureyev: Lifting the Curtain (2018) by David Morris and Jacqui Morris, a documentary featuring interviews with Nureyev’s colleagues, and archival footage with Margot Fonteyn and Erik Bruhn, and of Nureyev performing the modern dances of Martha Graham, Paul Taylor, and Murray Louis. His ballet performances can be seen in Romeo and Juliet (1966) by John Lanchbery, featuring Nureyev and Fonteyn; and Don Quixote (1973), directed by Nureyev with Robert Helpmann, with Helpmann as Quixote, Ray Powell as Sancho Panza, Nureyev as Basilio, and Lucette Aldous as Kitri. The book Nureyev: His Life was written by Diana Solway (William Morrow, 1998), followed by Julie Kavanagh’s book Nureyev: The Life (Pantheon, 2007).

Nureyev has been featured in a variety of dance documentaries, both biographical summaries and those recording his own celebrated performances. Other films featuring dance, including ballet and modern and popular dance include: Ailey (Jamila Wignot, 2022), an American Masters (PBS) portrait of dancer-choreographer Alvin Ailey Jr. (1931 – 1989), who had seen Monte Carlo’s Ballet Russe and Katharine Dunham, studied with Lester Horton, and performed on Broadway, before founding his own dance group and creating Blues Suite (1958) and Revelations (1960), Cry (1971), and a Charlie Parker tribute, For Bird – With Love (1984); and All That Jazz (Bob Fosse, 1979), focusing on a drug-addled womanizing choreographer, Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider), planning new work and encountering stress, leading to crisis and choice; An American in Paris (Vincente Minnelli, 1951), with the American being soldier-painter Jerry (Gene Kelly), who falls for a charming French girl, Lise (Leslie Caron); A Ballerina’s Tale: Misty Copeland (Nelson George, 2015), a documentary portrait of an American Ballet Theatre principal dancer, a dedicated, gifted young woman who was the first African-American in her position, and was supported by elders, but facing injury and recovery; Ballet 422 (Jody Lee Lipes, 2014), a record of the creation and performance of a ballet work by Justin Peck, who attended the School of American Ballet at Lincoln Center and worked with the New York Choreographic Institute and the New York City Ballet; Ballets Russes (Daniel Geller, Dayna Goldfine, 2005), a tribute to Sergei Diaghilev’s internationally celebrated troupe of artists and performers, featuring a year 2000 reunion of survivors; Billy Elliott (Stephen Daldry, 2000), about an English coal miner’s son prefers ballet to boxing and has a talent for it; Black Swan (Darren Aronofsky, 2010), in which ambition, competition, and mental vulnerability collide in a volatile drama, with innocence versus sensuality, and darkness versus light; Creature (Asif Kapadia, 2022), a filmed theatrical project featuring a story of a captured creature on an army base; and The Dying Swan (Alice Guy-Blache, 1925), featuring Anna Pavlova performing Mikel Fokine’s choreography, set to composer Camille Saint-Saëns’s “the Swan” from The Carnival of the Animals. First Position (Bess Kargman, 2012) is a documentary of the participation of six dancers in a competition to gain a place in a ballet company through New York’s Young America Grand Prix; and Jazzman (Karen Shakhnazarov, 1983) explores how jazz music faced repression in 1920s Russia, with a small group determined to play it and sustain audience and careers; Moulin Rouge (Baz Luhrmann, 2001), a musical drama in which a young man, Christian (Ewan McGregor), falls in love with a charismatic woman performer, Satine (Nicole Kidman), whom a powerful man covets, featuring contemporary music in a 1890s Paris; Nijinsky (Herbert Ross, 1980), a lushly beautiful drama written by Hugh Wheeler, based on Vaslav Nijinsky’s diaries and his wife Romala de Pulsky Nijinsky’s biography, starring pianist and ballet dancer George de la Pena, a soloist with American Ballet Theatre, as dapper, sweet but inspired innovator Nijinsky. and Alan Bates, so very good in Three Sisters (1970) and Butley (1974), as Nijinsky’s impresario and lover Sergei Diaghilev, a brave, practical, charming hustler who saw and supported distinctive talents, with the film focusing on the conflicts between art and success, love and possession, homosexuality and heterosexuality, and sanity and insanity, featuring Leslie Browne as Romala de Pulsky, Jeremy Irons as Mikhail Fokine, and Carla Fracci as Tamara Karsavina; Pina (Wim Wenders, 2011), a documentary of German choreographer Pina Bausch’s troupe, which combined theatre and dance, with everyday gestures transformed into art; and Polina (Valérie Müller and Angelin Preljocaj, 2016), a very, very engaging drama in which a Bolshoi ballerina becomes infatuated with a Frenchman and modern dance.

A Study in Choreography for Camera (Maya Deren, 1945), a black-and-white short film featuring Louisiana-born dancer and choreographer Talley Beatty in changing but recognizable environments, abstract and sensual (Beatty, a student of Martha Graham and Katherine Dunham, had his own company, toured Europe, and often focused on African-American history and experience); The Red Shoes (Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger, 1948), a memorable drama in which a dancer is torn between art and love, focusing on ballerina Vicky (Moira Shearer), composer Julian (Marius Goring), and teacher Boris (Anton Walbrook); Saturday Night Fever (John Badham, 1977) generates heat for observers of store clerk Tony (John Travolta) who finds pleasure, self-affirmation, and love on a discotheque’s dance floor in a generation defining musical drama (surprise: the popular Bee Gees music was added after the completion of filming); Save the Last Dance (Thomas Carter, 2001) portrays young people of different cultures sharing a love of dance, and becoming close, transgressing barriers; Sleepdancer (Rodrick Pocowatchit, 2005) depicts a mute Native American who dances in his sleep, a refuge from his own pain; Tap (Nick Castle, 1989), with Gregory Hines, Sammy Davis Jr., and Suzzanne Douglas, this musical drama focuses on hard times, temptation, and the possible transcendence of tap dance, and is worth seeing; Top Hat (Mark Sandrich, 1935), with Fred Astaire as tap-dancing Jerry Travers and Ginger Rogers as Dale Tremont in a tale of mistaken identity and show business; The Turning Point (Herbert Ross, 1977), time’s passage and what it’s made of two dancers, one who is still performing and the other who gave it up for marriage and family, starring Anne Bancroft and Shirley MacLaine, with Mikhail Baryshnikov and Leslie Browne as two young dancers who become entwined (Baryshnikov received an Academy Award—Oscar—nomination for best supporting actor); West Side Story (Steven Spielberg, 2021), an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet set in modern New York with gang warfare, the second film version of the musical by Jerome Robbins, Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, and Arthur Laurents (after 1961’s film by Robbins and Robert Wise); and White Nights (Taylor Hackford, 1985), in which Mikhail Baryshnikov plays a Russian dancer, Nikolai, who defected from Russia, and is declared a criminal for it, and finds himself, after a plane crash, back in Russia and in the company of an African-American performer, Raymond (Gregory Hines), who had chosen Russia in the name of revolutionary freedom but who lives in a confined space with his wife and performs old, once celebrated stage productions for a small audience.

Ballet is dance—it is the cultivation of grace. It allows for the contemplation of irreplaceable things, of irreplaceable times. It is, too, about bodies—about sex; and it is about the sublimation of sex. Rudolf Nureyev was a sensation, and a serious artist: for those who knew him only by reputation, he was a personality; and for those who knew his work, he was a power. The White Crow, a wonderful film, smart, engaging, attractive, and wonderful because of what it allows us to see—the birth of an artist, as it moves between the past and the present: the past is that Rudik was born to Tatars, a Turkic Muslim people that lived among the Mongolians, and born on a Trans-Siberian train, where his mother Farida was traveling to Vladivostok to meet his soldier father Hamet, and Rudik had an often isolated, impoverished youth, but he met helpful mentors and began preparations for distinguished performances; and the present is his visit to Paris, a personal and professional opportunity for advanced discoveries, for the possibility of liberty. Rudolf Nureyev was a force of nature—and of cultivated beauty. He seemed to reconcile masculinity and femininity; and he had a vigorously sexual presence. He had a good instinct for onstage costumes and an idiosyncratic offstage fashion sense. When interviewed, he could be shy, slyly witty, or plainly honest. He was part of the international jet set. Nureyev, not merely respected, but famous and rich, had a life that no one could have predicted.

Hamet, Rudolf Nureyev’s father, had studied Tatar philology and political theory in Kazan, a city of commerce, parks, minarets, science, and theatre; and Hamet had liked music. Farida, Rudolf’s mother, had wanted to be a teacher, before she began to have children. Joining the military was a practical choice for Hamet, who was a long time away from his wife and family. Rudolf Nureyev’s father Hamet had organized social events for the soldiers under his command, but one event, in Poland, led to trouble, and he was demoted for communication with foreigners, Polish soldiers. Hamet had been away from his family for about eight years, and he returned a stranger to his children, including his son, the only other male in the house. On a hunting trip, he left Rudik alone, asking him to wait for him; and Rudik, afraid, cries, and is found wailing when Hamet returns, notes Julie Kavanagh in the book Nureyev: The Life (Pantheon Books, 2007; page 17), the multifaceted accounting of Nureyev’s life, a book of facts and ideas and every kind of candor. The often solitary Rudik sometimes played with other boys, and liked the movie Tarzan, the Ape Man, but he was not the boy his father expected; and, Julie Kavanagh informs her readers, Rudik found others who could guide him as he wished, dance teachers such as Anna Ivanova Udeltsova, Elena Konstantinovna Voitovic, and Irina Alexandrova Vorinina. Their encouragement did not preclude prejudice: one of his teachers, Udeltsova “was instinctively prejudiced against Tatars, a word synonymous in her mind not with Byronic hot-bloodedness but with dirt and savagery,” seeing Rudik as an untamed urchin, according to Julie Kavanagh in Nureyev: The Life (page 23).

Rudik performed Russian folk dances and the classical exercises prescribed by his instructors; but his hometown Ufa did not have a ballet school until he was 15 years old, one he began to attend. Rudolf Nureyev auditioned for Leningrad’s Vaganova school in the Moscow hotel room of Abdurahman Kumisnikov and his wife Naima Balticheva, who were attending a celebration of Bashkirian literature and art in 1955, and they liked him. Rudi was 17. The Vaganova Academy (the Leningrad Choreographic School), on Ulitsa Rossi, was the same school attended by Russian prima ballerina Anna Pavlova and dancer-choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky; and Nureyev was assessed and accepted in Leningrad, 1955. Dance, the Kirov, in Leningrad, seemed more dignified than the exuberance of dance, the Bolshoi, in Moscow. Nureyev found Leningrad beautiful; and there he loved the Hermitage museum, in Rastrelli’s Winter Palace, appreciating its French and Italian paintings. He would participate in the ballet school’s 1958 graduation concert, performing with Alla Sizova a dance duet from Le Corsaire, a story in which a pirate leader, Conrad, sails to rescue his love, Medora, from a slave trader, Lankendem; and Rudi debuted the same year with the Kirov Ballet in Swan Lake, about a prince who falls in love with a princess turned into a swan by a sorcerer’s curse as are her friends (there is competition between a white swan and black swan; and they are only human at night, Odette and Odile—but the prince’s love can exorcise the curse).

Nureyev, a man of mastery and mystique, starred in Ken Russell’s biographical film Valentino (1977), about the popular Italian actor Rudolph Valentino who had starred in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) and Blood and Sand (1922); and Nureyev also appeared as a violinist, Daniel Jelline, with Nastassja Kinski in James Toback’s film of terrorism and surveillance, teacher and student, Exposed (1983). David Ansen in Newsweek wrote that “Rudolf Nureyev as Rudolph Valentino is a good idea that pays off. With his pansexual aura and astounding grace, he is an ideal choice to play the silents’ quintessential male sex object” while finding the film “a frustrating mixture of the near-sublime and the frequently ridiculous” (October 7, 1977). Nureyev would seem to be a natural subject for film. A full life portrait of Nureyev might be an epic of art, of love and sex and social life, and travel. Written by David Hare and directed by Ralph Fiennes, The White Crow, which shows us some of Nureyev’s early years, has the kind of fragmented structure that suggests the impact of the past on the present, the haunting of memory, the complexity of consciousness—modernity; but, obviously, with so many films using the same design, it is a demonstration of how radicality can become routine. On the site devoted to cinema critic Roger Ebert’s work and that of his colleagues, the reviewer Christy Lemire wrote of The White Crow, that the “script detracts from the potential power of the performance. It’s structurally awkward, jumping around in time needlessly and sometimes confusingly, rendering Nureyev’s story weirdly inert until the final 20-30 minutes” (April 26, 2019). Ironic that movement would suggest the inert—but that is one effect of repeated movement. Confusion might be another. “Structurally, the film is all chop and change, with Hare and Fiennes tacking back and forth across Nureyev’s early years. Some viewers will find the result too fussy by half; I liked its restlessness, and the sense of a chafed and driven spirit that refuses to be boxed in. We see Rudolf as a child, raised in severe poverty, with the colors around him drained to the brink of monochrome. We see him as a lanky youth, taken not just under Pushkin’s wing but into his home, too, and into the furtive arms of Pushkin’s wife, Xenia (Chulpan Khamatova). And we see him in Paris, in 1961, touring with the Kirov and dazed by the shock of the West—by its cultural storehouse as much as by its unfenced liberties,” wrote Anthony Lane in The New Yorker (April 26, 2019). The singularity of the artist, and of this story, maintains interest.

Of course, the strange thing about biographical dramas—and responding to them—is that we are seeing an interpretation (Ivenko) of an interpretation (Fiennes) of an interpretation (Hare) of an interpretation (Kavanagh) of a public figure (Nureyev) who may have been a self-invention (Rudik’s). Yet, the purpose of art is to help us see beyond the artifice into the real. The cultivation of Nureyev’s mind and body are the substance of The White Crow. “The classroom exercises that we see accurately depict the rigor and exhausting discipline, as well as the essential courtliness of ballet, which at heart is a physical expression of an ideal of human behavior. Fiennes also avoids the obvious but still sadly common mistake of casting a non-dancer in the lead and making do with body doubles and editorial fudging. Dance scenes are shot with refreshing simplicity, free from attempts to pump up the excitement with excessive cutting; the only real problem is that there isn’t enough dancing,” wrote Imogen Sara Smith of Film Comment (online April 29, 2019). Not enough dance? The film had a modest budget, according to its director. Variety magazine writer Matt Donnelly reported that Fiennes said, “I realized our resources were quite limited, and that my shooting time would be limited” and “We couldn’t afford to have great corps de ballet sequences, and we had only one very briefly glimpsed pas de deux” (April 18, 2019). Yet, Fiennes maintained his focus on Nureyev and his world: “Creating authenticity to the movie’s atmosphere, Fiennes cast almost exclusively Russian actors to play the part of Russian characters and French actors for the French roles, with the notable exception being himself,” noted Alisa Goz of Izba Arts, an East European arts platform (April 29, 2019).

Certain decisions that defy convention in life, in art, are controversial. Alexander Pushkin (Ralph Fiennes), the great dance teacher, is interviewed about Nureyev’s choice to desert Russia; and Pushkin says the young man, Nureyev (Ivenko), is interested in dance only, not politics: he would do anything to dance, and to grow into a greater dancer. The innovative choreographers were in Europe and America. Nureyev wanted to learn from them. Why? What drove him? The feature film, a drama (not a documentary), about one of the most charismatic and powerful dancers of all time, Rudolf Nureyev, returns us to black-and-white footage of a woman giving birth to a baby, to Rudi; and then into the future, a time full of color, when the young man looks out of window onto a different world. Nureyev (Oleg Ivenko) is handed a passport, arriving in Paris, and he is welcomed with the other members of the celebrated Kirov Ballet. Nureyev goes for a walk in the city, with Russian agents following him. Rudolph Nureyev, someone who read music scores for fun and liked dancer Vakhtang Mikheilis dze Chabukiani and musician Glenn Gould, film comedian Charlie Chaplin, and Jerome David Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye and the writers Dostoevsky, Konstantin Balmont, Valery Bryusov, and remembered Vivien Leigh in Waterloo Bridge (1940) and That Hamilton Woman (1941) as well as Deanna Durbin movies, was open to the world. Rudi sits in a café, and is interested in getting a toy train. He is a young man, hoping for accomplishment, beauty, sophistication, but he relishes the long desired boyish toy.

In the French theater, the Palais Garnier in Paris, actually an opera house, Nureyev (Oleg Ivenko) is disappointed to find that he is not scheduled for a first night performance, but he remains confident of his talent, his value, of his eventual fame. There is a recollection—a scene—of six years earlier, in Leningrad, when Rudi arrived from his hometown Ufa in the republic of Bashkir, to study and to live in a dormitory in Leningrad. Rudi was frustrated with his teacher Valentin Shelkov (Radoslav Milenkovic), who had an eye for talent but a military discipline, and is not encouraging. Rudi sought another teacher, Alexander Ivanovich Pushkin, a restrained man, a kind man, who had been a student of Agrippina Vaganova and Vladimir Ponornarev, and who gives Rudi simple instructions, articulating a sense, a vision, of narrative dance. In Paris, Nureyev, ever the curious student, always cultivating his own mind, walks to a museum, the Louvre, to await its opening, and the opportunity to view Theodore Gericault’s The Raft pf the Medusa, a painting showing the starving survivors of a shipwreck, which Nureyev studies. There is a flashback, a black-and-white scene of children at play, which the little boy Rudi observes (his own isolation is apparent). Rudi, years later, a young man, studies dance in Leningrad, taking classes but doing much work alone. Rudi examines sculpture, observing the look and positioning of the human body. Rudi asks his teacher, Pushkin, if he pleases him; and the teacher says Rudi does not displease him—and teaches him more, telling Rudi that there is a logic to steps, a larger story being told.

In Paris, Rudi makes an effort to talk to French dancers, Pierre and Claire, whom he has seen in magazines: Pierre Lecotte (Raphael Personnaz) and Claire Motte (Calypso Volois). While the Russian troupe practices, the dancers and their techniques are observed by interested French dancers. One of the French male dancers says that the French invented the ballet, but the Russians give it something unique: some think the French had precision and speed, and the Russians clarity, music and muscularity. Rudi has spirit and style, a way of taking the stage. In Russia, Rudi had worked on developing discipline: Rudi practices more than the others, who began dancing younger than he did; he wants to make up for lost time. Pushkin, Nureyev’s teacher, thought that Rudi neglected to eat, and had his wife Xenia (Chulpan Khamatova) bring Rudi food, French onion soup.

In Paris at the Palais Garnier, Rudi (Oleg Ivenko) prepares to go on the stage; and there is a memory of his mother going out into the cold to get groceries. Performing from Marius Petipa’s ballet La Bayadère, Nureyev dazzles the audience—which cheers, shouts bravo. Commenting on Oleg Ivenko as Nureyev, Courtney Escoyne in Dance magazine declares, He’s a leading dancer at the Musa Dzhalil Tatar State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre Company. Much of Nureyev’s technical prowess and pyrotechnics are considered par for the course for today’s male dancers, but we were quite impressed by Ivenko’s attention to detail—he even managed to recreate Nureyev’s distinctive arabesque line. He might not have quite managed the peculiar alchemy that made Nureyev such an explosive performer, (who could?) but he did capture the famed dancer’s ‘mischievous hauteur’ (as Fiennes put it) in his interactions with the other characters” (“A Viewer’s Guide to the White Crow,” Dance online, April 25, 2019).

Rudi (Invenko), after his well-received performance, meets Clara Saint (Adèle Exarchopoulos) and he goes to dinner with her, French dancers, and his young male chaperone—his friend and roommate Yuri. Rudi wants to see modern paintings, that of Picasso and Matisse. The French dancer—Pierre—says that The Raft is beauty made out of ugliness. Clara has lost a boyfriend (Andre Malraux’s son) in an accident, she tells Rudi, and she found Rudi’s performance transcendent. Rudi tells her that she must have a purpose in life; and tells her the story about seeing an opera when he was six years old, inspiring him, who was called a white crow. Nureyev had given himself purpose through dance and its requirements. One art led him to others—music, painting, sculpture, architecture, film and literature; and they led him to the larger world. In Leningrad, Rudi had been regularly visiting the Hermitage. He, also, visited other young people, a family and friends, who eat, drink, and discuss culture (the Romankovs), optimistic and thoughtful people, suggesting the possibility of community for someone whose life, whose culture, has been often solitary. Would Russia fulfill their hopes; or would it maintain its history of authoritarianism? In Paris, Rudi has the opportunity to pursue a variety of interests; and he wants to shop for a toy train with his new friend Clara Saint (Adèle Exarchopoulos); but he is angry to be offered the Trans-Siberian Express, possibly because it is one which he is too familiar with.

Rudik had been born on the train, as the family traveled to meet his father. In Rudik’s hometown Ufa, years later, when Rudik’s father Hamet returned from his long military service, and embraced his wife, Hamet looked around—and he saw his young son, whose mother then encouraged to greet his father, a stranger, who hugged him as the boy’s sisters observed. Is Rudik’s distance from his father due to his father’s stern character, or his father’s reservation about Rudik’s choice of dance as a career, which seems impractical? Does Rudik’s distance from his father motivate him to seek the friendship and love of other men? Rudik was certainly lucky with some of his teachers, choreographers, and collaborators—but I imagine one might say that of any first-rate career: quality is to be assumed; and fellowship is often an aspect of that. When Rudi visited the home of the Pushkins, his teacher Alexander and his wife Xenia, for dinner, Alexander Pushkin, again, talks about the importance of story in dance. True teachers are always sharing what they know, what they value.

Rudi (Oleg Ivenko) goes to a Paris nightclub with Clara Saint (Adèle Exarchopoulos), and sees modern burlesque—there is, of course, an air of liberty. That air is more common in France than in Russia—although, of course, many are inspired by an ideal France, an ideal that not even the place itself fully can embody. Similarly, constraints in a place known for constraints can feel even more oppressive. In Moscow, at the ministry of culture, Rudi complains about an assignment to Ufa, an opportunity to contribute to his hometown, to the Ufa Ballet, which Rudi thinks will stall his career. Rudi is told that the Soviet people paid for his studies, with a Bashkir republic grant, and he owes them something; but, then, an older woman dancer—an incarnation of Natalia Dudinskaya, a prima ballerina?—offers him a partnership at the Kirov (she will make him seem more talented; and he will make her seem younger). Unfortunately, Rudi falls, injures himself, tearing a ligament (it is 1959, according to Kavanagh’s 2007 Pantheon book Nureyev: The Life; page 63); and Rudi goes to the Pushkin household to recover.

Another early childhood memory: a forest excursion of Rudik and his father Hamet: his father lights a fire, and tells him to wait, and is gone a long time, leaving Rudik in the cold. There is ambiguity—is a lesson being taught; or is this a kind of abandonment, or indifference? (Julie Kavanagh recounts this episode in her biography of Nureyev and it does not seem any more illuminating. Rudik’s mother Farida, who had been frightened by being followed by wolves at night, was not amused.)

The White Crow: the present, the past; the past, the present. Visiting a chapel in France with friends, Rudi sees the beautiful, stained-glass work, with intricate carpentry. Rudi says the he would like to live there (obviously surrounded by beauty, by something revered)—and Pierre says that it is not easy to live in a church (with piety, with rules). Where would comfort be? In Leningrad, the care of Rudi by Pushkin’s wife Xenia becomes love; and she initiates an affair. Would Rudi be seduced in France? In Paris, when Rudi is out late, he is reprimanded, and warned, by Vitaly Strizhevsky (Aleksey Morozov), who asks about Clara’s wealth. The communists find the liberty and wealth of western countries dangerously seductive. Vitaly tells Rudi that this could be his last trip, if charges are brought against him.

In Leningrad, Rudi’s friend Teja Kremke (Louis Hofmann), an East German dancer, films Rudi practicing and performing, and they discuss what he can improve. Rudi and Teja Kremke, who had been introduced to sex by a thirty-five years old woman when Teja was a twelve-years old boy, lie in bed together (a scene that was censored when the film was shown in Russia); and the pragmatic Teja asks why the impetuous Rudi is still in the home of the Pushkins. Is Rudi being complacent; or is there an appeal that Teja cannot see? Has Rudi, quite simply, found a comfortable family? “You can’t resist foreigners,” says Teja, who thinks his intelligence and his foreignness are why Rudi likes him. (Rudi was infatuated with a Cuban dancer as well: Menia Martinez, a Cuban dancer and singer, a girl whose father was a diplomat and teacher, someone to whom Rudi proposed marriage.) “You dream of a world that isn’t this one,” Teja says. He encourages Rudi to travel, to move beyond the provincial. At a Russian restaurant in Paris sits Rudi with Clara; and Rudi does not want sauce on his steak but does not want to talk to the waiter. Rudi is afraid of the waiter, whom he supposes sees that Rudi is just a poor Russian; but when Clara tells him to talk to the waiter, Rudi expresses anger at Clara, who knows and respects him. Rudi is both arrogant and insecure. Yet, before Rudolf Nureyev was to leave Paris (where he saw Ben-Hur, which he did not like, and West Side Story, which he did like), Nureyev was given the Nijinsky Prize by Serge Lifar, a Russian choreographer who had danced with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes before becoming director (and reformer) of the Paris Opera Ballet, and who made his home in France. People recognized Nureyev’s talent, his value.

At the Paris airport, Le Bourget, when it is time to depart for the next stop on the troupe’s dance schedule, the French dancer Pierre gives Rudi a parting gift. Rudi is surprised to be told by Russian officials that Rudi is to go the Moscow for a gala for Khrushchev, not to London—then, he is told that his mother is ill. Rudi senses they are lying. Rudi thinks the Russian officials are trying to control and contain him. (His dance hero Vakhtang Mikheilis dze Chabukiani had been exiled from the Kirov by Soviet authorities for what was considered a misinterpretation of a role: Chabukiani was popular as Andrey in the ballet Taras Bulba, a character considered bad—and that was seen as counterrevolutionary.) Rudi wants to go on to London with the troupe; Rudi refuses to go to Moscow. Rudi knows the officials have done this to other dancers—and he fears prison. (Prison for enjoying liberty, as punishment for socializing?) Rudi asks Pierre to stay with him in the airport. Pierre has someone call Clara, who arrives, and offers Rudi advice, to ask for political asylum—and Rudi asks officials for political asylum, to remain in France. The loss of a great dancer is a symbolic loss—and it is a cultural tragedy for the nation that loses him, and a treasure for the nation that acquires him.

Ballet is dance—the poetry of gestures, the prose of steps: bourree and cabriole and entrechat and fouetté and glissade; and it was Rudolf Nureyev’s primary language, his art. Nureyev wanted to learn, to know, to live, to do, to impress, to seduce. He danced with the Royal Ballet in London and many other companies, eager for new experiences. “Ever since coming to the West he had ben regenerating every company he joined, enriching the classical repertory, and picking out potential principals,” wrote Julie Kavanagh in Nureyev: The Life (Pantheon, 2007; 557), a book full of description, full of photographs, of an exceptional life. Nureyev was a classical artist who experimented with modern dance, which focused less on technique and accepted gravity and the ground, the floor, as part of the work. Nureyev was a good teacher, and had exceptional taste for source material (Shakespeare, Lord George Gordon Byron, Henry James), although his reputation as a choreographer seems mixed. Nureyev became director of the Paris Opera Ballet (1983 – 1989), and near the end of his life began to learn to conduct an orchestra. Nureyev had a full life, with foes and friends—friends such as Albert Aslanov, Leslie Caron, Patrice Chereau, Rudi van Dantzig, Douce Francois, Maude and Nigel Gosling, Robert Hutchinson, Ninel Kurgapkina, Menia Martinez, Claire Motte, Stavros Niarchos, Peter O’Toole, Wallace Potts, Lee Radziwill, Jerome Robbins, Guy and Marie de Rothschild, Kostya Slovohotov, Sergei Sorokin, Robert Tracy, Violette Verdy, and Gore Vidal. He had a temper, sometimes high-minded and sometimes coarse—he was known to drop a bitch, and to curse and spit. Merde.

Yet, his glamour, like his talent, was transcendent. When Nureyev appeared in Ken Russell’s film Valentino (1977), the great film critic Pauline Kael in the New Yorker magazine (November 7, 1977) wrote, “He has the seductive, moody insolence of an older, more cosmopolitan James Dean, without the self-consciousness. His eagerness to please would be just right for frivolous, lyrical comedy, and he could play cruel charmers—he has the kinky-angel grin” (republished in For Keeps, Dutton, 1994; page 753). The conversant Kael, so full of appreciations and disdain, remains decades after her death, a good conversationalist, when she goes on to say of Nureyev, “He could be a supremely entertaining screen performer. He’s a showman through and through. He has the deep-set eyes of a Zen archer; the public is the target. At the ballet, one may be too aware of him as a personality, yet what can be faintly distasteful there—his being a star before he’s a dancer—is what makes him a full presence on the screen.” Pauline Kael recognized Nureyev’s possibilities—and possibilities were what he identified for himself and others. Kael speaks to us of the value of human perception. (Transcendent? One is reminded that Nureyev has been referred to as feral more than once—as not quite human, as more and less than human.) More recently, contemplating Nureyev in Valentino, Williams College English professor Christian Thorne in his web log Commonplace Book, remarking on fear and desire, on class and nationality and sexuality, in the film’s imagery and suggestions, observed, “>We can say that Nureyev was, in 1977, playing Valentino as Dracula, but we have to set against this the observation that Lugosi was already, in 1931, playing Dracula as Valentino. This is itself strong evidence that people were once scared of Valentino, but then we already knew that people—some people—were scared of Valentino, because he flaunted that off-white and insufficiently rugged form of masculinity, and because American women were really into it—or they weren’t just into it—they seemed hypnotized and made freaky by it. So the 1977 movie makes Valentino look more like a vampire than the real man actually did, but that’s because someone involved in the production intuited that Valentino had been one of the inspirations for the screen vampire to begin with. Heartthrob could be the name of a horror movie” (August 18, 2011).

When Rudolf Nureyev first defected, there were people in Europe and America that welcomed Rudolf Nureyev and others who did not as they wanted to maintain their own connections with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics’ ballet world—they wanted to present their own dancers in Russia. The Soviet Union, after the second world war, was a surviving power, and an opposing power to the United States of America, oppositional in might and philosophy. Yet, prestige could be found there—and money made there. The loss of a Nureyev was a defeat in a cold war, a war of beliefs and proxies and symbols. The matter might be funny if the competition had not been hedged by paranoia buttressed with nuclear weaponry. Meanwhile, Rudolf Nureyev was put on trial in absentia in Leningrad’s Municipal Court in Russia (the Pushkins hired a defense attorney), and Nureyev was condemned to seven years in prison. How cruel. Decades would pass before he received a 48-hour visa to return (without arrest or punishment)—when his mother was dying.

Why has Russia been such a cruel nation? Is it the authoritarian impulse? Certainly, Russia has given the world much: Anna Akhmatova, balaclavas, Mikhail Bulgakov, Chekhov, Dostoevsky, Faberge, Michel Fokine, Alexander Friedmann, Abram Petrovich Gannibal, helicopters, Matryoshka dolls, Konstantin Stepanovich Melnikov, Alexander Pushkin, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Ilya Repin, Saint Basil’s Cathedral, Alexander Scriabin, Tchaikovsky, Tolstoy, Turgenev, and the Winter Palace. I have found Russia fascinating for a long time. Geography was still taught when I was a boy, and I was impressed by its large land mass—and recall taking it on as a subject for a school project, for which I sent away for information and received a packet that included Pravda (Truth), the newspaper. Years later I would read about the last czar and his family, Nicholas and Alexandra (with their hemophiliac son and friend Rasputin, who was difficult to kill), and the politics of the revolution—and I loved the great Russian writers and I would see films such as Reds (Warren Beatty, 1981) and Nostalghia (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1983) and The Russia House (Fred Schepisi, 1990) and Father and Son (Sokurov, 2003) and Leviathan (2014).

Russia is a nation to which much mystery, malice, and misinformation has been attached. One has to do one’s own research—meeting people, reading books, seeing motion pictures. Films featuring Russia, and Russian culture, include: Alexander Nevsky (Sergei Eisenstein with Dmitri Ivanovich Vasilyev, 1938), about the defense of Russia by a rallying Prince Nevsky against German knights; Andrei Rublev (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1966), a drama focusing on an artist-monk’s response to war; Anna Karenina (Aleksandr Zarkhi, 1967), about family and betrayal, honor and shame, city and country life, love and loss, featuring the well-regarded Russian actress Tatiana Samoilova as Leo Tolstoy’s Anna; Ballad of a Soldier (Grigory Chukhray, 1959), a generous soldier finds opportunity to help others during his holiday at home during the second world war; Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein, 1926), on the mutiny of men on a battleship, in response to harshly horrid conditions, inspiring others to revolt; Brother (Aleksei Oktyabrinovich Balabanov, 1997), an older brother sets his younger brother on the wrong path, in this story of war and crime; Come and See (Elem Klimov, 1985), focusing on a boy’s desperate survival during a time of brutal war; The Cranes are Flying (Mikhail Kalatozov, 1957), in which a young couple meet in Moscow before the beginning of war, lose touch, but remember their commitment to each other; Doctor Zhivago (David Lean, 1965), doctor-poet Yuri (Omar Sharif) becomes infatuated with sensual young woman Lara (Julie Christie) during the Russian revolution; Dovlatov (Aleksey German Jr., 2018), expression and repression explored as a 1970s Russian writer is dedicated to his country but is silenced by it; Hard to be a God (Aleksey German, 2013), a contrast of times in a science fiction tale of threat and rescue; Ivan the Terrible (Eisenstein, 1944), a 16th century Russian ruler sets the standard for authoritarian, unifying power (suggesting, too, that the desire for power defies age and gender); Leviathan (Andrey Zvyagintsev, 2014), an ordinary man faces absurdly systemic corruption; Little Vera (Vasili Pichul, 1988), with Vera (Natalya Negoda) dismayed by dismal choices and limited resources in the Soviet Union; and Loveless (Andrey Zvyagintsev, 2017), in which a divorcing Russian couple try to find their lost son.

Meeting Gorbachev (Andre Singer and Werner Herzog, 2018), a portrait of the Soviet Union’s last president, Mikhail Gorbachev, and possibly its last great hope for a significant cultural change, who had been the son of peasants, a member of the Young Communist League (Komsomol), a law graduate of the Moscow State University, and a member of the Communist Party’s Central Committee—Gorbachev knew and attempted to reform the Soviet system and allow for more liberty—but the system could not embrace change without breaking, and Werner Herzog explores Gorbachev’s ongoing attempts to contribute to world peace; and Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears (Vladimir Menshov, 1979) released in US in 1981, in which three young women look for fulfillment; Navalny (Daniel Roher, 2022), a documentary about one of the most promising men and movements in Russia, the opposition leader Alexei Navalny, founder of a foundation fighting corruption (and winner of the Sakharov Prize), and the investigation into his August 20, 2020 Novichok nerve agent poisoning, one of several assassination attempts; Reds (Warren Beatty, 1981), in which art, bourgeois life, modernity, and revolution meet in this historical drama, a long but great film, starring Beatty as writer John Reed and Diane Keaton as his companion Louise Bryant, an emerging writer, with Jack Nicholson as Eugene O’Neill, Maureen Stapleton as Emma Goldman, and Edward Hermann as Max Eastman; and Russian Ark (Alexander Sokurov, 2002), with centuries of Russian art, culture, and history presented as a moving pageant, showing the glories of a nation. The Sacrifice (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1986) is a film in which Alexander (Erland Josephson) faces the future, spiritual contemplation, and a world war; and Solaris (Tarkovsky, 1972) is a contemplative futurist drama of isolation and turmoil, of mental disturbance in space; Stalker (Tarkovsky, 1979), a symbolic drama of hope within devastation, distraction or deliverance in a place perceived as a wasteland; They Fought for Their Homeland (Sergei Bondarchuk, 1975), about fellowship and heroism among Red Army soldiers protecting the Don River bridgehead; and The Thief (Pavel Chukhray, 1997), a story in which chance, compassion, and cunning follow war, featuring an accidental family.

Sometimes, and regrettably, the films that most directly address Russian matters are not made by Russians, cannot be made by Russians, as they would indict figures of power—and endanger the filmmakers. One film that was seen as conservative when it was made yet seems more prescient now is White Nights (1985), a film about dancers in Russia, about freedom and repression, starring Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gregory Hines, by director Taylor Hackford, with a screenplay by James Goldman and Eric Hughes and choreography by Twyla Tharp, production design by Philip Harrison, and photography by David Watkin. The motion picture, which looks very good, was shot in London and Finland with some genuine footage of Leningrad. The film’s lead performer Mikhail Nikolayevich Baryshnikov, born to Russian parents in Latvia in 1948, his father an engineer and his mother a dressmaker with an interest in ballet and theatre, began studying ballet in 1960 at twelve, entering the Vaganova Academy in 1964, joining the Kirov Ballet in 1967, with Soviet choreographers creating roles for him; but Baryshnikov defected while touring Canada with the Bolshoi in 1974—and he, subsequently, appeared with the National Ballet of Canada, American Ballet Theatre, and the New York City Ballet, and in several films—among them, The Turning Point (1977), The Nutcracker (1977) and Carmen (1981); and after White Nights (1985), he would be in Dancers (1987), The Cabinet of Dr. Ramirez (1991) and Company Business (1991). He is very good in White Nights: alert, angry, fearful, mocking, shrewd, sympathetic. “ With Baryshnikov as a ballet dancer who’d defected from Soviet Russia, Hines as a hoofer weary of being relegated to a ‘novelty’ act, and the pair’s uncommon chemistry during dance scenes that actually furthered the plot, White Nights today stands as a dance classic,” wrote Courtney Escoyne of Dance magazine (December 2, 2020).

The film White Nights begins with a man in bed, but that is not truly personal repose, rather it is the rendering of personal repose, part of a performance of Le Jeune Homme Et La Mort, a dance conceived by Jean Cocteau and choreographed by Roland Petit. Baryshnikov as Nikolai as the dance’s central figure rises from bed, beginning to dance in a modern studio apartment setting—with bed, table, chairs, and a large black-and-white sketched facial portrait as part of the decor. The dancer moves through the apartment, sometimes looking at his watch. A woman in a yellow dress enters, dances with him—then affixes a noose to the ceiling and brings a chair which he can stand on then step off, suggesting suicide (she is a figure of death). The woman leaves, and the man continues to dance, then steps into the noose, killing himself. Le Jeune Homme Et La Mort had been performed by Jean Babilée (1923 – 2014), and then by Rudolf Nureyev, before Baryshnikov did it: “Cocteau wanted the choreography to consists mainly of everyday movements electrified with emotional charge. Completely original—‘like a wild boy,’ an ‘angel-thug’—Babilée was incomparable at this, investing everything he did with meaning. Just the action of looking at his watch became an expression of violent internal revolt. He was the first contemporary classical dancer and, even in his seventies, would be an inspiration to Baryshnikov, who admired the way he could combine aerial lightness with a sinking, Grahamesque earthbound quality. Rudolf, however, intimidated by the idea of attempting a new genre, was not receptive to Babilée’s influence, and when, out of admiration, the older dancer offered to coach him in the role, Rudolf refused his help,” summarized Julie Kavanagh in Nureyev: The Life (Pantheon Books, 2007; page 359), adding that Rudolf, for his own performance, worked alone with choreographer Roland Petit and dancer Zizi Jeanmarie. Nureyev and Baryshnikov were friendly rivals over the years, each performing professional favors and tributes for the other; but at times Baryshnikov thought Nureyev’s technique imperfect (page 468) and Nureyev thought Baryshnikov’s dancing lacked soul (page 469)—but there was a time when, not long after his defection, the younger girl-loving Baryshnikov first visited Nureyev, and the latter, in search of the beast with two backs, chased the younger dancer around the house (page 470).

In White Nights, after Le Jeune Homme Et La Mort, the performer, Nikolai (Baryshnikov), receives great cheers, then soaks his feet backstage as admirers wait. On an airplane, the dancer Nikolai Rodchenko and his manager Anne Wyatt sit, drink—then the dancer records some notes for his conductor. The plane has trouble—there is a short-circuit in the pilot’s cabin. The plane will land in Russia—where the dancer was born, from which he defected and remains a wanted criminal. The dancer runs to the rest room to attempt to destroy his passport. The plane crash lands in Russia, with more than two-hundred survivors (four people have died). In Siberia, during a night that is as bright as day, an official, Colonel Chaiko (Jerzy Skolimowski), visits the injured patient without papers—Nikolai, who attempts to identify himself as French but is recognized. “Here’s you’re just a criminal,” says Colonel Chaiko, further insulting Nikolai by saying he is a great dancer but a pathetic man. To the public, including Nikolai’s manager Anne Wyatt (Geraldine Page), Chaiko claims Nikolai is too ill to be moved.

Meanwhile, Raymond Greenwood (Gregory Hines) is performing on Olney Island, Siberia, as Sportin’ Life from Porgy and Bess by George and Ira Gershwin with DuBose Heyward, the folk opera about an imperiled woman, Bess, who a crippled beggar, Porgy, attempts to save. Raymond’s Sportin’ Life, an exemplar of decadence (a drug dealer), sings and tap dances, looking and sounding good—suave. Raymond’s wife Darya (Isabella Rossellini) observes. Gregory Hines had been in Wolfen (Michael Wadleigh, 1981) and The Cotton Club (Francis Ford Coppola, 1984); and Isabella Rossellini had been in A Matter of Time (Vincent Minnelli, 1976) and The Meadow (Taviani brothers, 1979), for which she received an award, a silver ribbon from the Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists, for best new actress. Director Taylor Hackford, who hired an acting coach for the film’s production, was lucky to get experienced and talented newcomers to leading film roles.Hines is performing a wonderful number from Porgy and Bess, and the magic, humor and grace of the scene is breathtaking. It`s a classic screen moment that I know I`ll want to see again and again. Similarly, there are scenes with Baryshnikov that are spectacular all by themselves as he expresses both the joy and remorse he feels about his roots in Russian dance and his liberation from those roots,” wrote Gene Siskel in the Chicago Tribune, part of a mostly scathing review of what he considered a conventional spy story (November 22, 1985). (Conventional, a work that criticizes both the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics? A political thriller involving ballet dancers? An African-American exile? An interracial couple? Did unexplored attitudes about politics make reviewers nasty? “The cold war’s back, and Hollywood’s got it,” began Richard Corliss’s 1985 review in Time magazine. Did Ronald Reagan’s evil empire rhetoric make people wary of Russians as villains in cinema?) Chaiko visits Raymond and Darya to enlist their aid with Nikolai—Chaiko suggests a return to Moscow for them, for Raymond, an American who defected to Russia in search of a freedom he did not find at home, and Darya, who had been his translator when he arrived in Russia. Raymond listens, and Darya is skeptical.

Nikolai’s manager Anne (Geraldine Page) wants him back, as the Russians bask in the good publicity, they are getting for saving so many people after the crash; but the Russians put Nikolai (Baryshnikov), also known as Kolya, in the small, shabby apartment of Raymond and Darya Greenwood (Gregory Hines, Isabella Rossellini). The apartment has photographs of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, John Coltrane, Marvin Gaye, masculine icons, mementos of an abandoned national home. Nikolai (Baryshnikov) awakes, alert, tense, and asks if he is under arrest; and he is told, no, he is not—and Nikolai goes outside to test the theory but does not get far.

Hines as Raymond tells a biographical story, including his experience of American racism, while tapping—a drunken yet eloquent performance, complicated, pained. Tap, which melds British (Irish jig) and West African (gioube or stepping) music traditions, began in the 1700s in the United States; and it can be joyful entertainment. However, Raymond’s torturous history—a history that led him to seek Russia as an alternative—is infused in the intense dance he does. Like more than a few enlightened African-Americans, he may have been attracted to the promise of a classless society, to communism: among them, Langston Hughes and Lovett Huey Fort-Whiteman, Harry Haywood, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, William Lorenzo Patterson, Paul Robeson, Homer Smith, George Tynes, Dorothy West, Richard Wright—and Angela Davis; some of whom visited Russia or even lived there for years, finding jobs and creating families. Of course, the theory of freedom and its practice are not the same—and increased minority migration numbers and personal prejudice create their own stresses in a nation. In White Nights, Raymond has suffered, is suffering. Raymond’s wife Darya (Rossellini) hurts for him, comforts him.

The three leads, Baryshnikov, Hines, and Rossellini are attractive and give strong performances, especially Baryshnikov—who is intense from the beginning and has rapport with everyone. (“With White Nights, it’s evident that he’s almost as much of a powerhouse personality in films as he is in the dance world. Unlike Rudolf Nureyev, to whom the motion picture camera isn’t especially kind, discovering a lightweight presence within the one-of-a-kind ballet star, Mr. Baryshnikov brings to the screen all of the dynamic force and intelligence that distinguish his dance performances,” wrote Vincent Canby of the New York Times in his November 22, 1985 review of the film when it opened. Unfortunately, Canby, who liked Taylor Hackford’s film An Officer and a Gentleman, 1982, and Against All Odds, 1984, and appreciated the supporting performances in White Nights, found the screenplay ludicrous, calling the film a makeshift melodrama.) Yet, in White Nights, Chaiko, Nikolai, Raymond, and Darya are aware of each other’s character and differing motives: to be persuasive, something true will have to said; something genuine will have to be offered—or threatened. Subsequently Colonel Chaiko (Skolimowski) takes Raymond (Hines) to a rock mining site. The visit contains an implicit threat—it is a view of the kind of work Raymond could be assigned. Chaiko wants Raymond to convince Nikolai to dance again in Russia—after Russia gave Raymond shelter, education, and the opportunity to perform, Chaiko thinks this is how Raymond can repay the nation. Interesting: each man, Raymond and Nikolai, looked to the other’s country for the more complete freedom he could not find in his own. Did each nation articulate something the other could use more of—equality? liberty? Raymond does talk to Nikolai about the defector’s dancing again in Russia, how it would be welcomed, that he could have the respectable life he had before.

In Leningrad (St. Petersburg, built by Peter the Great as an imperial city), beyond the statue of Lenin, and the imaginative buildings, the three, Nikolai (Baryshnikov), Raymond (Hines), and Darya (Rossellini), drive in a car to see Nikolai’s old apartment, a luxurious place—roomy, full of antiques and personal items. (The scene in the car, filmed elsewhere, is imposed on actual Leningrad photography—although Hines and Rossellini did visit Leningrad for research.) Darya and Raymond look out of Nikolai’s apartment window, she wishing they could stay. In a rehearsal room, later, Nikolai plays the piano as Ray talks to him. Nikolai mocks Ray with different dance styles, suggesting Nikolai be given a ruble for each pirouette (one-foot spin) he performs. Nikolai’s mockery is interrupted by a visit from an old friend who has become a cultural power, Galina Ivanova (Helen Mirren), who is still angry about Nikolai’s abandonment and the interrogation she faced from authorities (she had to defend herself to the KGB, Komitet gosudarstvennoy bezopasnosti—the committee for state security; and her passport had been confiscated for years). Galina offers Nikolai a place at the prestigious Kirov Ballet, but he is skeptical—and asks her to help him escape, which outrages her. Later Chaiko (Skolimowski) tells Galina that Nikolai would dance only at the company’s premiere, not for the whole season—Nikolai would be interrogated and his fate would be a political decision, not an artistic matter.

Raymond, alone, improvises in the rehearsal room to music that Nikolai has brought, a long, intense exploration. Nikolai, after pretending to take a shower, leaves the studio to see how far he might get—again, not far; and he sees young girl dancers—who do not know him (he has been erased from Soviet history). There is the beginning of a delicious dinner and drinks for Nikolai, Raymond and Darya that is interrupted by Chaiko, who arrives enraged that Nikolai attempted to speak with young students; and Chaiko sends Darya home, to Siberia. Ray, angry, hits Nikolai. The men argue briefly, but Raymond is overwhelmed with pain and Nikolai consoles him. White Nights does not have the slackness or sentimentality of many musicals, nor the predictability of many political thrillers. Informed by history and culture—controlling communist bureaucracy, flawed democracy, ballet, Gershwin, tap dance, and a batch of popular genre songs—it is a fresh amalgam.

Ballet is dance—effort and energy, strength over struggle and stress; and motion is infused with meaning, and scored to music, creating memory. What Nikolai, facing entreaties and threats, does remember is his frustration when he lived and danced in Russia. Nikolai visits Galina in a great theatre, where she is on stage reviewing production plans. She wants to perform an evening of Balanchine work: George Balanchine (Georgiy Melitonovich Balanchivadzem, 1904 – 1983) had been born in St. Petersburg, the son of a Georgian republic composer and culture minister (father), and a mother who admired ballet. George Balanchine began studying piano at five and dance at nine; and he, Balanchine, graduated from the Imperial Ballet School and the Conservatory of Music. Balanchine performed with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris, where Balanchine began to choreograph, traveling throughout Europe. Balanchine founded the School of American Ballet with Lincoln Kirstein in America; and as a touring company, American Ballet (which had a residence at the Metropolitan Opera). With Balanchine, Kirstein, and Morton Baum, the New York City Ballet was created; and Balanchine’s many ballets and dances—more than 400—include The Nutcracker (1954) and Don Quixote (1965). His work was innovative—and he represented the kind of modernity that made traditionalists in Russia wary. (However, Balanchine’s commitment to collective onstage work—he preferred to affirm the group rather than individuals—was in line with a communist ideal; and Balanchine resisted working with the charismatic Nureyev.) The Balanchine evening Galina imagines is often proposed, often postponed. Nikolai is pessimistic. Galina turns on the theatre’s lights, and Nikolai sees (and we see) its great beauty. Nikolai is impressed but he knows that he cannot dance there with the liberty he can in the western world—and he dances for her to the music of Vysotsky, a repressed artist, music that is liberating for the listener: Vladimir Vysotsky (1938 – 1980), a singer-songwriter of thoughtful commentary, political, satirical, someone whose popular work was circulated privately. Nikolai’s dance is a demonstration of personal power, unsanctioned power.

Galina (Mirren) meets an American embassy official, Wynn Scott (John Glover), at a reception, and acknowledges Nikolai’s presence there in Leningrad. She will help Nikolai. Consequently, a plan of escape begins to be fulfilled. In the rehearsal room, each dancer warms up—Nikolai stretching, Raymond boxing and jumping—and they begin to bicker a little, with Nikolai suggesting racial prejudice and Raymond suggesting jealousy regarding Nikolai’s attention to his wife. Thinking that Nikolai is interested in Darya, Chaiko has her returned from Siberia to Leningrad—not realizing that was Nikolai’s plan to reconcile Raymond with his wife. Nikolai and Raymond discuss the risks of attempts to escape. They rehearse, observed by the camera, by Chaiko: they perform a duet that somehow fits them both, with tapping, leaps, poses, turns. Raymond talks to Darya about leaving Russia, as she washes her hair, about the two of them taking control of their lives. Nikolai tells Galina, in her office, that he will dance again (they both know they are being recorded)—and on the television, she puts on a tape of him dancing when younger (she whispers to him where he can meet the Americans). Nikolai, Raymond, and Darya argue for the listeners, for the surveillance men and tape recorders, as they plan how and when to leave: they want freedom.

(DG, May 2024)