Tennison S. Black is the author of Survival Strategies (UGA Press, 2023), which won the National Poetry Series. Their work has appeared or is forthcoming in SWWIM, Hotel Amerika, Booth, Wordgathering, and New Mobility, among others. They are the Managing Editor at Sundress Publications and Best of the Net. Multiply disabled themselves, they are the editor of the anthology on contemporary disability, A Body You Talk To. They reside in Washington State and teach writing at Arizona State University.

Tennison S. Black is the author of Survival Strategies (UGA Press, 2023), which won the National Poetry Series. Their work has appeared or is forthcoming in SWWIM, Hotel Amerika, Booth, Wordgathering, and New Mobility, among others. They are the Managing Editor at Sundress Publications and Best of the Net. Multiply disabled themselves, they are the editor of the anthology on contemporary disability, A Body You Talk To. They reside in Washington State and teach writing at Arizona State University.

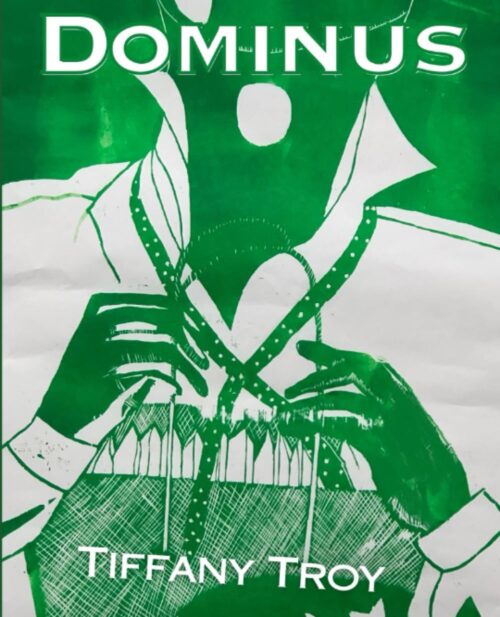

Tiffany Troy is author of Dominus (BlazeVOX [books]) and co-translator of Santiago Acosta’s The Coming Desert /El próximo desierto (forthcoming, Alliteration Publishing House), in collaboration with Acosta and the 4W International Women Collective Translation Project at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She is Managing Editor at Tupelo Quarterly, Associate Editor at Tupelo Press, and Book Review Co-Editor at The Los Angeles Review.

Tiffany Troy is author of Dominus (BlazeVOX [books]) and co-translator of Santiago Acosta’s The Coming Desert /El próximo desierto (forthcoming, Alliteration Publishing House), in collaboration with Acosta and the 4W International Women Collective Translation Project at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She is Managing Editor at Tupelo Quarterly, Associate Editor at Tupelo Press, and Book Review Co-Editor at The Los Angeles Review.

Survival Strategies is arranged in three parts. This collection of poems follows a narrative arc and features a speaker who is returning to the Sonoran of her birth after many years away, and takes us with her on a journey of acceptance. Like Survival Strategies, at the heart of Dominus is a search for that gold center of the heart. Set in the fictional city of Ilium, the poems in Dominus are episodic and feature characters striving for the better in a world shaped by the law, patrimony, and lyric poetry.

Survival Strategies is arranged in three parts. This collection of poems follows a narrative arc and features a speaker who is returning to the Sonoran of her birth after many years away, and takes us with her on a journey of acceptance. Like Survival Strategies, at the heart of Dominus is a search for that gold center of the heart. Set in the fictional city of Ilium, the poems in Dominus are episodic and feature characters striving for the better in a world shaped by the law, patrimony, and lyric poetry.

Tiffany Troy: How does “I Was Born for Rainy Days But” open the door to the world in Survival Strategies? To me, it establishes the female reader, who is gone through marriages, who is returning back to the arid landscape of Sonoran to find herself.

Tiffany Troy: How does “I Was Born for Rainy Days But” open the door to the world in Survival Strategies? To me, it establishes the female reader, who is gone through marriages, who is returning back to the arid landscape of Sonoran to find herself.

Tennison Black: That poem came out of me reckoning with, and trying to cope with, the trauma that had haunted me and that was coming up in full-force as I was facing returning to the region where I’d experienced it. I wanted my graduate degree but I was scared to go back to AZ and deeply reacting to the idea as I’d avoided it for most of my life precisely because of how it made me feel. But I had received a great offer from ASU to pursue my MFA there and I wanted very much to study with the specific people who taught there—so I had to reckon with that paradox.

Regarding the female presenting persona of the speaker—while I am personally nonbinary, it took me almost a whole lifetime to fully embrace my identities primarily because of the ways that the culture in which I was raised was so deeply insistent on not just the gender binary but also compulsory heterosexuality. So in this poem you see some of me trying to express my fear at once again being immersed in that culture while also acknowledging that when I’m there, I’m perceived much differently than what I know to be true about myself, and I’m not accepted for who I am but instead am living inside those things that have been so damaging to me (and so many others). In the line about wanting to feel comfortable being called a woman, being perceived, for example—but there’s also me pushing it aside almost feeling a sense of “don’t think about that.” And in this I’m comforting myself by saying that there has to be something I can find comfort in as I did when I was child, predominantly in the flora and fauna.

Tiffany I was enthralled with this collection from the outset. There’s so much I want to ask but I’d better start at the beginning and work my way through. “Dominus” as a title has incredible gravitas. It strikes a note, for me, something like an echoing bell in a stone chamber. At once a carrying note while also being sacred and reverent. How did you land on this title and also how do you see it informing the collection as a whole?

TT: Thank you so much for sharing that, as I feel your deep sense of attachment to the unique geography of Arizona in Survival Strategies, as when you speak “of sharp things and dry things, scratchy and hard things.”

Dominus is such a great title, isn’t it? Haha, I can say that because I wasn’t the one who came up with the title, my thesis advisor and teacher of seven years, Dorothea Lasky, did! The trajectory of finding a title is also a bit a journey, from Judges to Jurisdiction to Dominus. It draws from Yeats’ poem “Ego Dominus Tuus” though if I’m completely honest with you, I wanted to present the idea of the Master–Father–mastery of the self–in this context of religious iconography and the Latin helped me to capture it. Master is a complex character, isn’t he? But he is a compelling character to me precisely because it’s hard to pin him down–and what makes him charming is also what makes him dangerous and cruel.

What about you–what is the thought process behind the title “Survival Strategies”? What are some craft techniques you utilize to build and re-define history in the “sunniest place on Earth,” as land plundered and stolen by the colonials? I am intrigued and inspired by the place as a character.

TB: Journey is exactly right for me, too. The work was originally one long poem with a title that was suggested by my thesis advisor, Cynthia Hogue. That was The Lilac Seed. But also at that time I was really focused on a different arc and a different approach to the work. As my approach shifted from that into singular poems the title shifted again. And then a third time when I found the arc it lives in now, one that confronts but also has more agency in the speaker’s view. It was at that time that it landed on Survival Strategies because I realized at that point that I was actually trying to explain how unlikely it was that the speaker (as well as others who have faced this culture) survived at all. I know it seems like it’s the desert that people are surviving—but the point overall is that the desert is the least of it—that the desert is far friendlier than the culture that to this day dominates that world. The desert for me is the inverted foil to the culture.

Regarding history—I don’t think I get to redefine it, nor did I attempt that in Survival Strategies and I hope it’s not taken as such. What I felt and strove for was that I could not explain the place, the time, nor the culture I come from without also stating plainly that colonialism is at the root. My ancestors came here from both Eastern and Western Europe and migrated West therefore I directly benefit from colonialist genocidal history, but I don’t have to also be complicit in the erasure of that fact just because it makes me uncomfortable. My stating that openly is not intended in any way to absolve either myself or my ancestry from any wrongdoing and harm—nor is it intended to make myself appear virtuous. Nor is it intended to be any great revelation—it’s just a statement of truth, no redefining included. As I see it, it’s the versions of the history of cowboy culture that portray that culture as settlers (rather than colonizers) that are attempting to redefine history, not those that take a view that centers the harm that culture has done. So what I tried to do was state that truth as I see it with matter of factness and to avoid laying any claim to stories that are not mine to tell as well as to avoid any sense of absolution.

TB: Ahhh! I love that you touched on Master, so can we talk about characterization? One thing our works have in common is this sense of narrative and of course, the characterization that accompanies that narrative. When I think of characterization personally, I think of persona expressed vs persona crafted. So given that this is poetry and not necessarily a plotted narrative in the prose sense, how did you approach the beings in this work, including that of Master? And do you feel you can/could/would ever include them in any sense again?

TT: Yes! As I was reading “The Mother and the Mountain,” I definitely saw the parallels in our work, in thinking about how we each draw from personal experience to craft characters like the cowboy and the mother, and the mother’s mother. The distinction between persona expressed and persona crafted is also very useful as a dichotomy. For me, the persona crafted presents or expresses itself through in connection with the other personas. So the tension in the poems of Dominus lie in the conflict between the characters. I was interested in crafting characters that are not one dimensional but encompass the immigrant American experience and a non-traditional family dynamic.

Could you speak to me about the way in which characterization works for you–I’m so intrigued by the distinction you made between persona expressed and crafted. To me, the elements in Survival Strategies definitely felt nonfictional in the sense that it felt rooted in real life. At the same time, it also felt beyond the historical, familial, in the sense that characters morph into landscapes and transcend the body, in some ways. There were also some ways in which the family is mythologized. How much research goes into this process?

TB: This is probably a lot of hokey to lay down, but the way I think about people in writing is that there is a person and the expression of their persona is very different from who they are really, and then again the persona as seen by someone else, in this case the writer, is even further removed because it’s all about how we perceive that persona, not how it is, inherently, which is itself removed from the person already. Essentially the versions of us that live in other people aren’t us and they also aren’t how we express ourselves, they’re some odd mish-mash of their perception and experience that we mirror to them through our expression. So the first expressed—how the person expresses themselves as opposed to how they see themselves, and the second is crafted or how we see that person/character and that leads the writer to how they in turn express—which is, at this point, a full three leaps from the reality of a person. I see it like this: Who they are > how they express themselves > how that expression hits the mirror for the receiver > leading to how they’re perceived > how that understanding is expressed by someone else to another > how that is then aso bounced over a mirror before being perceived, and on unto infinity.

And in Survival Strategies there’s all of this—the filtering through of how I experienced these stories, but in the middle of that process is a neurodivergent child’s brain—then the filter of time and memory as well. So it’s rooted in my experience but rooted then filtered through my perception of the expression of those things and people, and then again through time and my own growth from child to adult—so I tried to keep the view rooted in my truth because I’m aware that my truth isn’t THE capital-t Truth, but it is mine. So I wanted to honor the child who lived these experiences because she really had some tough times, but I also didn’t want to step too far into the personas of the other people because I don’t feel that with my experiences I can do so in a way that honors their truth.

Can you talk more about your thought process as you crafted these characters? How did you ensure they had conflict? What did you draw on to build them? And then! One thing that fascinates me is how you went from “conception of this character” to expression on the page. Can you touch on your thought processes in that?

TT: Wow! Your explanation taught me so much about this idea about perception and experience. Your question is fascinating too because actually what ends up happening in my writing process is that I start off with a scene where conflict is inevitable and where the characters want to change or conform other characters to their conduct in some ways. I begin with a phrase or a scene, I set the character in action with one another, there’s a coda or turn in the action or its aftermath, and the timbre of the characters conflict color the emotional core of the poem and shape its form.

Turning a moment to overarching structure, how did you decide upon the sectioning of your poems? And how about sequencing within sections?

TB: When the project was one long poem it had to flow in a way, from one idea to the next so everything was interconnected. And I would’ve thought that when I took it apart and started to form distinctly separate poems they’d have stayed in that order but they didn’t—not even close. Though I wish I could say that I had some grand idea of the arc from the start, I didn’t. The reality is that I took the pieces and laid them on the floor a lot and walked the trail until something stopped me—where I felt there was a gap, or something didn’t make sense. And I kept moving things around with every version of the project (there were many versions of this project over time). In this way, over a period of years it came together until the day I suddenly realized it was done. I wish I could say that’s part of how I work but it’s just how it worked this time.

I keep coming back to something you said early on and I wanted to revisit it before we close our talk because it struck me as so deeply valuable and intricate that it needed a second look. You said, “I wanted to present the idea of the Master–Father–mastery of the self–in this context of religious iconography and the Latin helped me to capture it.” Can you talk about how you got to this connection and what it holds for you, personally? This feels really exquisite to me. That weaving of these formative experiences with self-mastery ideals and concepts of Master and father all at once. Like this glorious air current slipping by with so much more than mere air. And in there, somehow, I also wonder how this has been for you, laying out things that were once at rest deep within?

TT: I can totally picture the idea of the poet walking the trail until it was done. And thank you so much for your second look. I think ultimately the burden of the speakers in Dominus is self-imposed, in the sense that the speakers really want to make Master, who doubles as a kind of father, proud. But Master doesn’t exist in a vacuum but within a legacy of patriarchy where the head exists in the man. If so, then the philosophy underlying Ilium is patriarchal, and Baby Tiger needs to prove herself not only for her own sake, but often to the surprise of this world. In this context, sometimes the taunts of the Master feel cruel in the same way women have borne. That is challenged in Dominus through icons like Maria Goretti or Procne who fought for themselves to their own demise.

Turning to you, I have learned so much and am wondering if you can close us out with any closing thoughts for your readers of the world?

TB: If I were to close at all in anything it would just be to say thank you. For being here, there—for reading, for caring, and for existing. Thank you, always.