Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

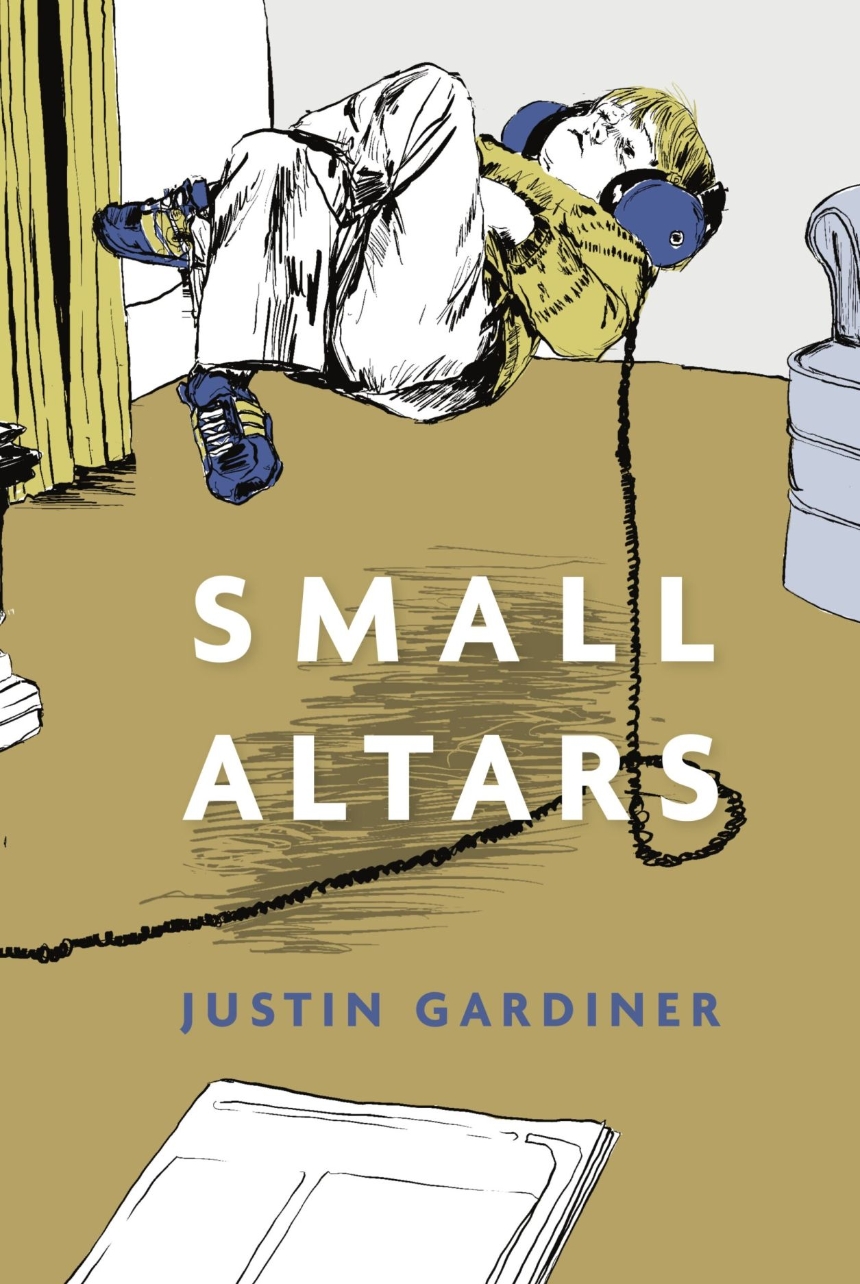

Small Altars

by Justin Gardiner

Tupelo Press

ISBN: 9781961209060, April 2024, $21.95, 70 pages

Justin Gardiner’s meditation on his disabled brother’s death and the implications of comic book superheroes that runs through it amounts to an extended elegy in which Gardiner examines his own feelings of shame and guilt, all part of the grief that quietly saturates the narrative. While the reader gets a sense of the arc of Aaron Gardiner’s life, Small Altars is written in short, episodic passages, jumping back and forth in time, some describing family scenes, others expository discussions of medical conditions, from schizophrenia to various cancers, the elements of comic book composition (both “on the page” and in conception as character and plot), biographical descriptions of various historical personalities – Claude Debussy, Arthur Rimbaud, Paul Verlaine, Georges Remi among them – and more. Each of these passages is a “small altar,” indeed, a memorial to a sad, tragic life. Though lovingly cared for and looked after all his life by his parents, Gardiner’s brother, who lived his entire life in Eugene, Oregon, died alone, in a hospital bed, at the age of forty-four.

An Associate Professor at Auburn University and nonfiction editor of the prestigious journal, The Southern Humanities Review, Justin Gardiner recognizes the unfair hand his older brother was dealt, and a kind of survivor’s guilt colors his impressions. But though Aaron was “born with a borderline learning disability,” was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia in his twenties and spent the rest of his life “in breakdowns, treatments, a revolving door of doctors and meds,” ultimately dying from synovial sarcosa, a soft-tissue cancer that spread to his lungs, Gardiner recognizes his brother’s gifts as a musician and an indispensable childhood companion in general, certainly a vital part of his life. He recalls the movies they saw together, the games they played, from Yahtzee to fantasies like Top Secret, Dungeons & Dragons and, significantly, Marvel Superheroes.

Comic book characters, indeed, are important to understanding Gardiner and his brother. Iron Man, the X-Men, the Hulk, all of the superheroes in the Marvel Comics universe are “flawed characters that struggled with inner-demons and self-doubt,” Justin Gardiner notes. Implicitly, he places Aaron in the same cast of characters, plagued by inner demons of his own (“he would make comments that made no sense – about cameras hidden inside walls, policemen following him home at night.”).

Aaron’s superpowers included playing Debussy’s Claire de Lune on the piano, engaging in fantasy play, journaling (Justin discovers a couple of dozen journals after his brother dies), making his brother laugh. “Regularly defying death is part-and-parcel of the superhero job description,” Gardiner writes elsewhere, and it’s clear he wishes his brother had likewise dodged death. But grief, Gardiner ironically observes, does not become Thor.

“If this were a Hollywood movie, or even a decent comic book, we could expect, here, a turning: Then one day it happened, and he became…,” Gardiner writes wistfully in that heartbreakingly futile if only tone we’ve all experienced. And yet, he confesses, “I had often viewed my brother as an imposition.” This he confesses at his brother’s memorial service, with which the book begins and to which he returns now and again.

Aaron is Justin’s burden. He recalls going to a party while still in college at which a drunken guest, with whom he’d gone to high school, tells Justin that he once worked with Aaron at a pizza joint for a while. “We used to call him Igor because he could hardly turn his neck,” the drunk boy sneers, and he goes on to make more disparaging remarks. Justin is confused by his own reactions, which are basically to ignore the guy. He wonders if he should he have hit him, to defend his brother’s dignity. Was he cowardly?

Gardiner feels guilty about living so far away from his needy brother, though at the same time he recognizes it as an escape. His parents and sister and brother-in-law all live in Eugene, and he feels as if he is shirking his responsibilities, even as his parents recognize Justin has a destiny of his own and urge him not to stay behind for their sake. “‘You’ve got to promise us,’ our mother says again. ‘We’ve made arrangements,’ our father adds. ‘He’ll be taken care of.’”

While Justin is off pursuing his career across the country, Aaron works at menial jobs. For more than a decade he lived in his own apartment, and for the final ten years of his life he worked as a janitor at the Pearl Buck Center in Eugene, a pre-school designed for children whose parents struggle with cognitive challenges and developmental disabilities. The set-up at Pearl Buck definitely improved the quality of his life. Yet Justin had never been inside the building before his brother’s memorial service, another source of guilt.

But he still has misgivings. “Even in his last better years of mental health, my brother was not an easy person to be around. He was tone deaf to most social cues and norms.”

Small Altars is an understated but overwhelming meditation on grief, the conflicting emotions of love and sorrow and guilt it encompasses. It brought to mind my own brothers who died before me, one at the age of 57, the other at 63. Neither suffered from a disability (one did have a history of drug abuse), but I do often experience a sort of guilt for having somehow failed them, and I’ve built my own small altars to their memories. One lived in Albuquerque, and the only time I went there was for his funeral; the other lived in LA, and the only time I visited was when he’d been diagnosed with stage 4 cancer. Both had their inner demons. Could I have done more? Justin Gardiner’s grief feels so familiar. Small Altars is a loving and introspective contemplation of family and loss.

About the reviewer: Charles Rammelkamp, is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore and Reviews Editor for The Adirondack Review, and author of Mortal Coil, A Magician Among the Spirits, and See What I Mean? published by Kelsay Books in 2023.