Reviewed by Donna Fleischer

Reviewed by Donna Fleischer

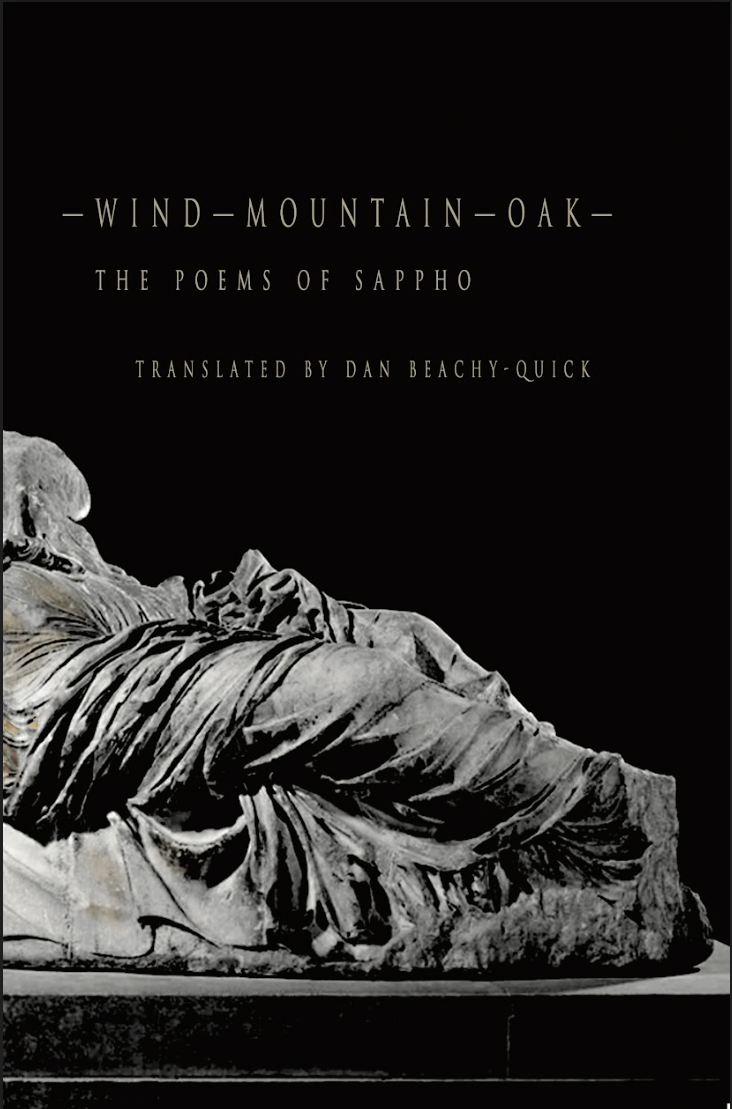

Wind—Mountain—Oak: The Poems of Sappho

trans. by Dan Beachy Quick

Tupelo Press

March 2023, Paperback, 242 pages, ISBN-13: 978-1946482815

This book reviewer has discovered that — WIND — MOUNTAIN — OAK — The Poems of Sappho, the newly translated complete Sapphic fragments by the contemporary American poet Dan Beachy-Quick, and published by Tupelo Press, is a reading experience equal to the poet who entrusted her voice of daring imagination to reach a time far beyond her own. Sappho (630-570 BCE) composed and played music, songs, and lyric poetry in her now extinct Greek Aeolian dialect of over a thousand years ago. These were eventually compiled in nine volumes of scrolled ancient papyrus from which one poem is intact and the rest are in fragments. How does this book shape the original mostly oral nature of the songs and poems and how does it articulate movements that were originally performed as rites of birth, sacrifice, marriage, friendship, rivalry, battle, and death?

Sappho’s first words ‘bedrock’ and ‘whisper’ appear immediately on the verso rather than traditional recto page, signaling the arrival of something different and new. Both words are typographically lower-cased, left-aligned, and separated by a vertical white space of about eight lines. These auditory incantations lean into the book title — WIND — MOUNTAIN — OAK — of three upper case words which begin, continue, and end with four em dashes or level virgules typeset for longer pauses of breath and voice than the shorter pauses or caesuras known as vertical virgules which intertextually populate Sappho’s fragments throughout the book. This deliberate grouping of glyphs or marks interrelate written, spoken, seen, heard, danced, and summarily felt or experienced interrelations of the poet’s songs in her chorus of one or many.

Dan Beachy-Quick translates as if he is beside Sappho on her footpath to something quite never before seen and heard. A grove of oaks shake with mountain winds in the book title fragment from a pastoral world of alliteration, rhythm, and rhyme. Our collective species memory enlivens, quakes to a time when we were one with the natural world, calling out holophrases to goats and dogs, other herders, and goddesses and gods. A lyre graphically depicted on intermittent recto pages complements the lyrical text fragments throughout the book, as if a musician grazed on strings in a pre-historical world when Nature was a kind of music and words spoke-sung in a unity of oneness, a birthing of Poetry.

This translation bypasses reliance on the numbering system conventionally used by scholars to identify each fragment; it lets Sappho’s words loose as limbs unfolding, each to each, page to page, until the half-verse of five lines ends the book:

. . . more green

than grass I am, dying

just a little from needing

so much, so I see me

as I am—myself . . .

Beachy-Quick describes Sappho’s lyrical voice on page 16 of “Note on the Translation”: “Sappho’s eponymous meter begins with the fever of heavy stress then transitions through the middle of the line into a calmer order at the end . . . . as if each line begins with the heart startled into a panicked pulse, that then grows accustomed to the startle.” His decision to keep the shape and movement of her meter from breaking up is one he admits may be wrong, and if so, he apologizes to the poet herself. Nicely done. He says further that he regards each word as an epic poem in the journey of one who risked love and loss to have lived a real life despite restraints of rules and conventions of control over what may be fully possible in being human.

Beachy-Quick reminds us, “Sappho is a love poet.” His translation materializes new shapes and movements for the poems to re-gather original energy from Sappho in her world. Her final half-verse sings of she who needing so much challenged so much in order to be free.

This translation unifies. It is not about Sappho’s life or the work that has been lost. It is as direct a reading, I venture, as can be done in translation into a nowadays American English that shows off some of Sappho’s fun in language play. Up to now, the contemporary Canadian poet, Anne Carson’s translation, If Not, Winter (Random House, 2002), has been this reviewer’s most direct experience of Sappho’s poetry. “Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works” (Cambridge, 2015), by Diane J. Rayor has been said to possess a likewise forward rendering I leave others to ponder.

Beachy-Quick writes on page 17 “. . . I wanted to offer an ordering of these poems that give some sense of that epic journey any given life is, one that leaves us [as] it leaves most heroes, limping on a wounded foot. There is a motion [to] how the poems move . . . which might teach us — as Sappho hints —to see ourselves as no more than we are.” This is fresh translation and revelation.

About the reviewer: Donna Fleischer (b. 1950, USA), is a poet, essayist, and curatorial blogger at word pond.