Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

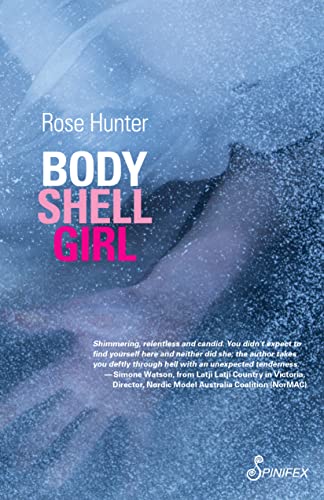

Body Shell Girl

by Rose Hunter

Spinifex Press

March 2022, $21.95, 160 pages, ISBN: 978-1925950502

Rose Hunter’s harrowing, brutally honest account of her life as a sex worker in Canada at the end of the twentieth century is both revelatory and cautionary. Told in vivid verse form, she recounts her reluctant initiation into the sex industry in Toronto, in response to her stark economic circumstance – always a means to an end – through the collapse of her dreams of film school and a career in filmmaking, her hardening into “the life,” to her resignation that sex work is all her life will ever amount to.

In a prose epilogue, Hunter tells us that she spent a total of ten years in the sex industry. The three parts of Body Shell Girl that boomerang from Toronto to Vancouver and back to Toronto cover the first two years. Subtitled, “A Memoir,” the collection of poems is a concise, courageous recollection of traumatic events. As Hunter writes in her epilogue:

I hope what I’ve written helps someone. I also hope it shines a light on an industry that does enormous damage, overwhelmingly to women and girls, and that dehumanises everyone. I am grateful to have survived the industry and the damage it left behind, and to be able to tell my story in a public way, in the form of this book.

To begin at the beginning, then, in “Portal, 1997” Hunter, an Australian citizen, describes looking for jobs in this new country; a soul-sucking position in a photo shop that doesn’t last long, an interview for a paid internship at a documentary film company that doesn’t materialize.

but for now I needed a job, any job

I got more interviews

but didn’t get those jobs either

The BA in English doesn’t qualify her for much, she realizes, and “rent loomed // and nothing in reserve.” Hardly believing she’s doing so, she answers one of those ads in the classifieds section of the Toronto Star:

Masseuses wanted!

$$$

cash paid DAILY

no experience necessary

She calls the number in the ad, and

“I love your accent!” The voice on the other end

like campfires and marshmallows and you’re invited

well this was the warmest reaction I’d received

since I arrived in the country; OK maybe not quite

but it was the warmest reaction from anyone

I’d rung about a job

so I wrote down the address

At the interview, Lisa, the receptionist, tells her what the job entails:

“Nude hand jobs basically,” she said, and shrugged

as though summarising the weather

She starts right away. Her first client “looked a bit like my father.” Hunter describes the surreal experience, the man’s gasps and clumsy fumbling at her breasts, the “surge of almost firmness in my hand,” the man’s gasps at the moment of climax, her sticky fingers.

how strange how strange how strange

and how if I kept repeating that

I couldn’t hear my other thoughts

Later, she meets the boss, an Eastern European woman named Zuzanna (“Call me Zu.”) She’s paid $140 for her evening’s work, a fortune. Financial salvation.

Hunter describes the milieu, her co-workers, the boss, in brief but vivid details. Zu is like a mother hen. “I can tell that you’re a nice girl,” she tells the narrator. She advises her how to groom, how to dress, how to behave. Zu looks out for her employees; she wants them to succeed. Zu is an admirable person in her way. She tells Hunter: “And don’t do full service. Ever. Don’t even think about it.” And later: “but I want you to remember this: you are not a whore.” Zu elaborates:

“You can keep your eyes on your goals,” Zu said.

“Like Lisa. She’s doing a degree.”

“Final year,” Lisa said, sifting round in her rice. Well, now

my ears pricked up like frost tipped

and the whole world sparked with

possibility. Maybe this could pay for more than rent.

Like qualifications for a job I actually wanted

like that internship

a career I wanted, even

maybe I could go to film school!

Hunter describes her co-workers (Lisa, Phoenix, Andrea, Erika, Tanya, Deja) almost as if they were Oliver Twist’s companions in Fagin’s troupe of street urchins. But as the poem, “This Gets Messed up Pretty Quickly” clues us in, there are also very frightening aspects of the job – the violent clients, their demands. In “The Deeper You Go, into the Ocean,” she writes about a client threatening to kill her. It’s a heart-stopping moment. In the poem “Rick” she writes about her coping mechanism, from which the book’s title comes, zoning out, pretending she’s not really there.

think of my body as a shell

that I could vacate, not as metaphor, or symbol

but as a real possibility

Hunter is also bulimic and alcoholic and has serious self-esteem issues. She writes about these things with unflinching frankness in poems like “Ladybugs and Wishes.” But for a time she does feel as if she “belongs.” In the poem, “Chariot,” she is in a car with her co-workers, telling jokes.

Zu’s crack-up like a cascade and windchimes

rolling down a staircase

and me giggling too, and feeling like wrapped up

and glad

they are on our side, I thought

In Part II, the narrator goes to Vancouver, to enroll in film school! This is like a success story, right? After grimly paying her dues as a masseuse, she can dedicate herself to the art of filmmaking, right? Wrong.

and my idea was to do well

so I could get a job after, and start my career

the phrase gave me goose bumps

like yes, then my life would start

But she still needs money to live, and in Vancouver she has to work in a full-fledged brothel, not a mere “massage parlor.” Things go from bad to worse. She is raped in the poem, “Red Velvet Suite.” Her work visa has expired and when she goes to the U.S. border to renew it, she is not allowed back into Canada. She gets a ride from another sicko, who, after terrorizing her, lets her go. (“Gutter trash,” he said. “Not even worth it.”) The university has caught wind of her immigration problems, and she does not finish her coursework. It’s like it has all been for nothing.

Defeated, she returns to Toronto, where she joins an escort service, full-on prostitution, too ashamed to return to Zu’s parlor. As she writes in “Home Sweet,” the first poem in Part III:

and so I went back

to that place where I knew what to do

and how to do it

it was always there to catch me

and wasn’t that what a friend was

what a home was?

In a series of poems – “Mr. Donut,” “I Am,” “He Is” – Hunter profiles the escort service clientele, their behavior and personalities. “Money: Some (More) Points” details the prostitute’s fluid relation to money – accumulating it and spending it. “Savings: LOL,” indeed.

By the end of the sequence, nothing’s really changed. “Future Poem,” the final poem, echoes “Home Sweet” as it ends:

this was what a friend was, what a home was

I thought

This is such an appropriate way to end this sequence, emphasizing the bleak despair, the utter hopelessness of the sex worker. In the epilogue, Hunter tells about her struggles to extricate herself from the life, fleeing to Mexico, and even there the slow, excruciating process of changing her life. In this sense, Body Shell Girl is inspirational, but mostly it is bleak and terrifying and so vividly honest.

About the reviewer: Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore and Reviews Editor for The Adirondack Review. His latest book, Catastroika, was published in May 2020. A chapbook of poems, Jack Tar’s Lady Parts, is available from Main Street Rag Publishing. Another poetry chapbook, Me and Sal Paradise, was recently published by FutureCycle Press. An e-chapbook has also recently been published online Time Is on My Side (yes it is). Another chapbook, Mortal Coil, is forthcoming from Clare Songbirds Publishing.