Reviewed by Amy Strauss Friedman

Reviewed by Amy Strauss Friedman

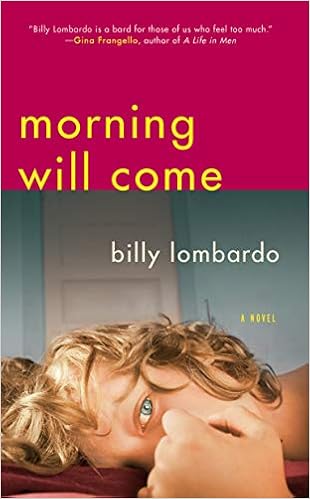

Morning Will Come

by Billy Lombardo

Tortoise Books

ISBN-13: 978-1948954075, April 2020, 191 pages

“The whole world is a very narrow bridge.” – Rabbi Nachman of Breslov

Billy Lombardo’s novel Morning Will Come captures a family in the unrelenting grip of grief. When Audrey and Alan Taylor’s teenage daughter Isabel goes missing, they and their two younger sons Dex and Sammy must contend with what remains, with the continuous presence of her absence. Lombardo both magnifies and expands this absence through language tight and unsparing. He wisely chooses not to make flowery the on-the-ground, every day, grinding loss that the Taylors drag through their ordinary lives. The triumph here is that they go on; hobbled, throats bound, and worse for wear. But they go on.

The book begins at a restaurant called Khyber Pass, at a dinner to celebrate Alan’s return after a summer researching abroad. In Pakistan, the Khyber Pass serves as a bridge connecting towns and valleys, and has functioned as a critical route for Eurasian trade. Like the Pass, Isabel connected this family, served as an integral spoke in the wheel of its existence. When she disappears shortly after the dinner, the wheel spins out of control, stumbles as its other spokes struggle to make up for the missing piece. By chapter two we know that Isabel is gone, and because this fact is frontloaded in the novel, the story of Isabel’s family is told through the lens of destruction. Like a 9/11 retrospective, their world has already collapsed. What’s left is to rummage through the remains, and to attempt to rebuild on forever faulty bedrock.

Who are they now without Isabel? Who are they as parents, as siblings, as human beings? And how do the holes in their hearts define their futures? “It is difficult to document /a disappearance,” Maggie Smith writes in her poem “Small Shoes.” For its effects are everywhere and nowhere. In fact, Isabel is barely mentioned in the book, though she permeates everything. She’s the inveterate run in the fabric of the Taylor family. And her unfinished story allows for all kinds of projection for those left behind. They attempt to recast themselves in the lack. Dex now projects himself into the role of the oldest, reaching out to protect his younger brother Sammy in new ways. Alan tries connecting with an old lover, to time travel away from the dull, pulverizing pain that insists and insists. Sammy grows up too fast. Audrey searches for the moon once shining just for her that now casts only a dim pall her dusty cheeks. Forced out of their former selves, the Taylors are left attempting to reanimate their shedded exoskeletons, the ghosts of who they used to be.

Alan leaves his position as a professor and researcher in the wake of Isabel’s disappearance to pursue law school and the prosecution of violent criminals. He reshapes his life to save the daughter already lost to him, and so each attempt is another failure. Audrey’s role as mother diminishes in her sons’ eyes. They see her as human, no longer the savior that parents appear to young children. At times they call her Audrey; her role of mom tenuous as her human frailties become apparent to her kids long before they’re meant to. Alan does the same: “He could not keep from comparing the two Audreys–the new and the old. The old Audrey was everything he ever wanted. She was a great mother, she was smart, she was funny, and she was beautiful.” That Audrey disappeared with Isabel.

In fact, Audrey and Alan do little but remind each other of their own frailties. Each sees in the other a fallibility at the heart of their own heartbreak. Each in mourning, their own pain bumping against the immutable pain of the other, an attempted violation of the laws of physics. Two objects of agony fighting to occupy the same liminal space. “Moments of sweetness” followed by “years of sadness,” Lombardo explains. For if they’ve failed to protect their daughter, what kind of parents and people must they be? All of this compounds as Audrey’s father slips away into dementia’s grip, her mother fading physically the whole way. Their impending absence (and the father’s already mostly absent mind) recalls and recalls the loss of Isabel. In fact, he thinks that Isabel is Audrey; they are one in his consciousness, and in so many ways, in hers. His parental worry lingers and haunts when so much else has faded.

When Isabel disappears, her parents lose their future. And every new day is the future, every new moment another death. “I haven’t heard you say her name in years,” Audrey writes to Alan by email after they’ve separated, suggesting the air is flammable and Audrey’s name the match. In her place, Lombardo highlights experiences of men violently falling: one stranger jumps to his death from a building in front of Dex and Sammy, the other falls inside a bus in front of Audrey. Life is violent, fragile, in perpetual peril. Under these circumstances, how can any of us truly love each other?

And yet, even young Dex knows its value. Staring at his mother inside a store with Sammy through the windshield of their car, Dex decides that when Audrey returns he will “reach for her hand and…set his hand on top of hers…he would keep it there. Goddamn it, he would keep it there.” Lombardo reminds us that love is all there ever is, all that’s worth the fight. Morning Will Come so very worth the read.

About the reviewer: Amy Strauss Friedman is the author of the poetry collection The Eggshell Skull Rule (Kelsay Books, 2018) and the chapbook Gathered Bones are Known to Wander (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2016). Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net, and her work has appeared in Pleiades, Rust + Moth, The Rumpus, PANK, and elsewhere. Amy’s work can be found at amystraussfriedman.com.