Reviewed by Marek Makowski

Reviewed by Marek Makowski

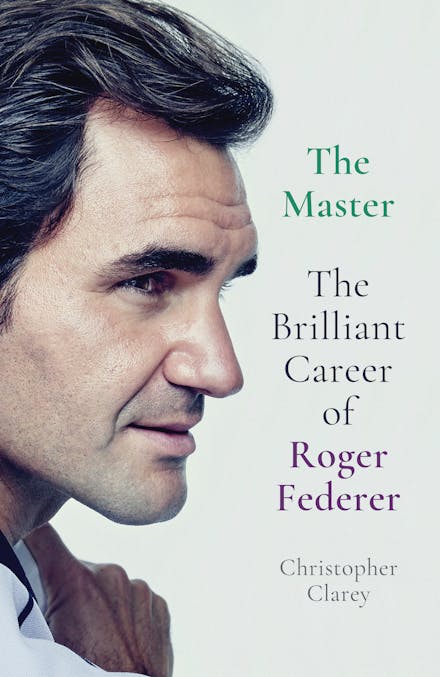

Roger Federer, The Master

by Christopher Clarey

Hatchette

Trade Paper, Aug 2021, ISBN: 9781529342062, $32.99

Roger Federer’s life story could be arranged by scenes of crying: on court, when he struggled with emotion in youth; when he ran out onto the streets of Toronto, only 20 years old, after learning that his coach died; after beating Pete Sampras at Wimbledon in 2001; during his victory speech after his first major; after his loss to Rafael Nadal at the Australian Open in 2009 (“God,” he said to the crowd, “it’s killing me”); when he fell to his knees as he won his only French Open championship; when he jumped in disbelief with his miraculous victory against Nadal at the 2017 Australian Open for an eighteenth Grand Slam; and in his 2019 defeat to Novak Djokovic at Wimbledon, after holding match points at 8-7, 40–15, when he made it to the locker room and collapsed.

In his biography, The Master, Christopher Clarey recounts these scenes in the rest of the known narrative. After Carter’s death, Federer realized he could not waste his talent. He dominated the sport in the mid-2000s. At the end of the decade, Nadal emerged as his great and more successful rival. In the early 2010s, Federer struggled with injuries and Djokovic’s new dominance. At the end of the 2010s, Federer returned from knee surgery, played more freely and aggressively, extended his records, and remembered the feeling of success.

Then—and this is not written—he watched his records fall. The Master ends with the story of The Champion: Djokovic resisted Federer in the 2019 Wimbledon final, Federer and his calm risky strokes, his two match points. But, at the French Open last fall, Nadal tied Federer’s record for Grand Slams. Djokovic tied it at Wimbledon this July. All while Federer labored to recover from two knee surgeries for one last great return, while he lost to low-ranked players in empty stadiums at small tournaments and to the No. 14 Hubert Hurkacz at the Wimbledon quarterfinals, which ended with Federer’s only 0-6 set in his career at The Championships.

What do disappointment, age, repeated injury, physical deterioration, last hopes, and the triumphs of rivals do to a sportsman and the narrative of his life? With so much unwritten, we can only ask, Why now? Why not wait until after the Big Three retire?

Clarey seems to agree that a Federer biography would be best after his career ends, and he biographizes as if from the future: “While Roddick retired at thirty, Federer played on (and on), even into the 2020s.” But he covers the early career well, coloring it within interviews gathered during his career as a tennis journalist. Nadal tells him, When I compete, I love to be there and fight for the win.” And, after a pause: “Maybe … I like more fighting to win than to win.” (Unfortunately, this brings strange commentary out from the author: “Nadal is still far too young to be thinking about a tombstone, but if he ever orders one from Amazon, that sentence should be on it.”) Federer says, “As much as I like the records, to break those or own them, I guess for me it’s really the breaking part which is beautiful, not the owning part. Because no one can take away that moment. … That first moment when you take that step or that leap into that sphere where nobody has been before, that is really inspiring.” And, in the best of the quotations, Federer describing winning the French Open in 2009 as a series of images: “Me on the knees in disbelief. The racket dropping right next to me. The orange clay, so vibrant and vivid. Holding the trophy up and kissing it. Tearing up during the anthem. Those are the moments I see most right now.”

Clarey also relays anecdotes about Federer’s generosity, like how he surprised an advertising team at Nike by offering to serve its members as a cashier and barista, then walked from table to table, introducing himself. Clarey also attends to the many who developed Federer’s character and technique in the formative years: Pierre Paganini, who built up Federer with “tennis-specific training” rather than general running and weightlifting; Christian Marcolli, a former FC Basel soccer player who became a performance psychologist and taught Federer to manage his thoughts in between points; Peter Carter, who worked on Federer’s style and early game; and, of course, Mirka Vavrinec, who stopped playing in 2002 because of injuries and who has managed Federer’s business decisions and family life while advising him on his career. Through these portraits, Clarey shows how many people it takes to shape what we consider a singular talent, as well as how many rise with promise in youth but do not transcend like the rare greats.

But this is all tennis. What is the life? For a long biography written after years of access to Federer and the sport, Clarey says almost nothing new. Reading The Master, which the publication materials call “a major biography,” is like watching someone write all around a human life. Clarey doesn’t answer any of the questions that would make a biography, or life-writing, and he includes almost no private scenes. This is important for any book, but especially for Federer, who has mastered his self-brand. A former fitness trainer of his says that “the Federer we see on court today is a manufactured product of Nike’s marketing that represents the values we want to give tennis”—an idea that the scenes of sudden crying challenge but that Clarey could have further explored.

Clarey also avoids thinking through how Federer conceives of fashion and design, what Federer sees in the faces of schoolchildren his foundation finances in Africa, or how signing with Golden Set Analytics in 2017 influenced what we call the poetry of Federer’s game. He leaves out information about Federer’s relationship with Peter Carter’s family after his coach’s death or how Federer’s perspective on Carter and death have changed in the past nineteen years. He does not dwell on the dislike between Federer and Djokovic. When he writes that “at age sixteen” Federer “decided to stop his formal schooling and focus entirely on becoming a tennis professional,” he adds nothing about what the experience was like. When Federer falls for Mirka at the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Clarey mentions a few linescores but nothing about first looks, conversations, late evenings, love. And when Clarey writes that Federer “avoids politics, cultural rubbing points, and public score settling,” he does not ask the most important question any journalist can: why?

I wanted to admire this book because I feed on Clarey’s articles for the New York Times and am mystified, enchanted, inspired, thrilled by the Big Three’s endless poetic encounters. Finally, I thought, an opportunity for someone who has seen Federer up close, for decades, to write the hidden dramas of his life. I wanted to admire this book—trust me when I say I wanted to, even tried to love it—but it showed me little and disappointed me more than anything I have read in my life.

Clarey struggles with the long-form, which exacerbates many of the problems of sportswriting: an overreliance on quotations, redundancy, forced transitions, uninspired diction, scattered thinking, the clutter of unnecessary information, and a lack of pacing and analysis. Although he avoids the many linguistic sins of L. Jon Wertheim, King of Sports Clichés, Clarey still commits a few, so in his book, you will read of bitter defeats, feet on accelerators, absorbed blows, rebounds, pedestals, damage done, brash predictions, optics, attention-centers, and grit. He massacres language and defiles the unity of a paragraph. And he cannot abandon his lust for the cutesy kicker, delivering lines better saved for tweets or the ends of game stories. Developing Federer, he writes, “was a long-term project. To date, no Nobel Prizes have come from it, but that does not mean it was not a noble effort.” He also writes that “tennis superstars get a lot of free footwear, but it is rarer that they are able to put themselves in others’ shoes,” and that “Federer was … not much of a book reader, although he clearly developed a fondness for record books.”

This is an overexerted prose, an extended article, a book-length Wikipedia page, a series of interviews patched together with supplementary quotes, camera shots from replays of matches, and trivia—not the story of a life, not a biography.

Its author could have written more out of his own experience as a reporter on tour. At the end of the first chapter, he declares he will do so: “This will not be a Federer encyclopedia. … Instead, this book aims to be episodic and interpretative, built with care around the places, people, and duels that have mattered most or symbolized most to Federer.” You can hear Clarey testing out the personal voice, and he offers opinions almost apologetically, keeping them brief and modifying them with phrases like, “in my view” and “from my vantage point.” It would have been better had he let in more of the unobjective, more of the self, filling his pages with his own analysis and experiences on tour rather than box scores and quotes.

When he commits to this conceit, though, he succeeds. The writing lifts: he thinks about his youth, how “tennis was one of my passports to inclusion in the next community, the next school, the next team” in his frequent moves with his father, an admiral in the Navy. He tells the reader, in a natural style and voice, that “I have come to prefer watching tennis on clay: for the movement, for the tactics, and, on a purely aesthetic level, for the way the shadows extend across the red clay in the late afternoon in Rome or Paris.” He comments on how “Federer has long had a tendency to speak about Nadal as if he were a natural phenomenon, like a king tide or a tropical storm.” And, in the book’s most human scene, Clarey describes how he returns from the day in Chicago with Federer: the sportsman boards a private jet while his biographer flies home late at night in the crowded economy class, lands at Logan Airport, cannot find a taxi, and walks three miles in the silence of early morning, meditating on the differences between us and the rich. The half-personal chapters that show Clarey following Federer through cities for promotional tours or exhibitions disturb the book’s balance and give more narrative weight, for example, to a day in Chicago to do PR for the Laver Cup in 2018, than to Federer’s wedding or his realization that he could improve his behavior in matches (Federer tells Clarey, “That was a career-defining moment for me,” but Clarey only grants it three sentences of description).

Instead, for much of the book Clarey recounts matches, and he reduces the glory and thrill of Federer’s tennis to mechanical writing, which lacks so much detail that each sentence, meant to recount the drama of three and five sets, becomes meaningless (“Federer responded by taking a 4–0 lead in the second set, but Roddick rumbled back to 4–4 only to lose the set … Roddick did not crumble. He took a 4–2 lead in the third set…”). Clarey narrates Federer’s 2005 Australian Open semifinal against Marat Safin, one of the great battles of the decade that the author claims “will go on our short lists of matches to savor,” in this automatic prose: “Every set was tight. Many points were short and explosive, but the best was strength against strength…” He concludes, “Best to have been there to truly understand.”

This stands out as a sad admission by one of the sport’s best reporters. Clarey repeats the sentiment during his account of the 2008 Wimbledon final—“It was best to have been there, of course”—which reads as an apology, or a statement that he cannot not put those transcendent experiences into words. But sometimes Clarey shows he can take us there. He does so at the end of the chapter about the 2005 Australian final in a rare moment of elevated, detailed prose that animates the night: “The score line was 5–7, 6–4, 5–7, 7–6 (6), 9–7, but it is best to commit other things to memory: like the gasps of the crowd in the midst of so many rallies; like the racket Federer threw late in the fourth set, his new-age veneer developing cracks under Safin’s pressure; like the sight of Federer barefoot and hobbling with his head bowed as he walked down a corridor inside Laver Arena shortly after his defeat.”

Later in the book, Clarey recounts how he tried to admire the 2008 Wimbledon final while preparing to submit his story on deadline. “In time-crunch cases like this,” he explains, “we prepare for what are called switch ledes: two versions of a story, one for each possible champion. One of my ledes had Federer extending his reign in the fading light; the other had Nadal ending it in the fading light. It would take more than an hour to find out which lede needed to be deleted.”

An occasion for poetry—and isn’t this true of sport and life? How many alternatives we have seen deleted, how different we could have been. Federer’s life and the qualities that rouse us to cherish him have not been written in full. They are flashes of gestures lost in the spotlight and secret. They have been deleted, like the unfulfilled possibilities in his life and career. Clarey claims his book is episodic, but he leaves us with a book of episodes undescribed, holes in pages, blank lines.

About the reviewer: Marek Makowski is a writer who teaches composition at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He lives and plays tennis in Chicago. You can read more of his work at marekwriting.com.