Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

New Cemetery

By Simon Armitage

Knopf

January 2026, 112 pages, ISBN-13: 978-0593804018

Simon Armitage is one of the most acclaimed poets alive today. He has been the UK’s poet Laureate since 2019 when he took over from Carol Ann Duffy. His body of work is extensive and varied with over twenty poetry collections along with nonfiction, novels, translations, theatre, television, collaborations and the list goes on. Armitage’s newest book New Cemetery is an expanded version of a chapbook of the same name published in 2017. This version contains sixty-nine poems following an terrific opening piece of prose writing titled “Moths” which is more of an essay than preface, contextualising the work and describing the development of the cemetery and the way in which the book came together through that process. Each of the poems is written in the same cascading tercet format with generally no more than five words per line. These lines progress like steps, gently but persistently moving forward at a walking pace, keeping, as Armitage says in “Moths”, with his “frame of mind” and “length of stride” at this time of life. The overall effect is soothing and reverent, taking on the quiet progression of his subject matter, a new cemetery built near Armitage’s home in West Yorkshire. He also invites us to see each tercet as a winged moth: “two wings and a body part” or at least moth-like in the poem’s fragile diminutive nature.

New Cemetary moves in a linear progression with the cemetery as character, complete with narrative arc, from “bulldozers/peeling back turf” to fully occupied with those “unable to love/but capable still/of being loved.” Each poem is headed with a type of moth: “Funeral confetti. Nocturnal flak. Lunar emissaries” enclosed in brackets. These are not poem titles though they sit where a title would be, but rather, the dedicatees of the poems, their evocative names providing its own form of found poetry: “[Common Quaker], [Dark Brocade], [Pine Beauty], [Blossom Underwing], [May Highflier]”. These are all real moths that can be looked up and their presence impacts the poems that follow in subtle ways as moths are simultaneously invisible, using camouflage and other methods to blend into their surroundings, and, on close inspection, exquisite, with unique and intricate patterns, muted but rich autumnal colours, unusual sizes and textures.

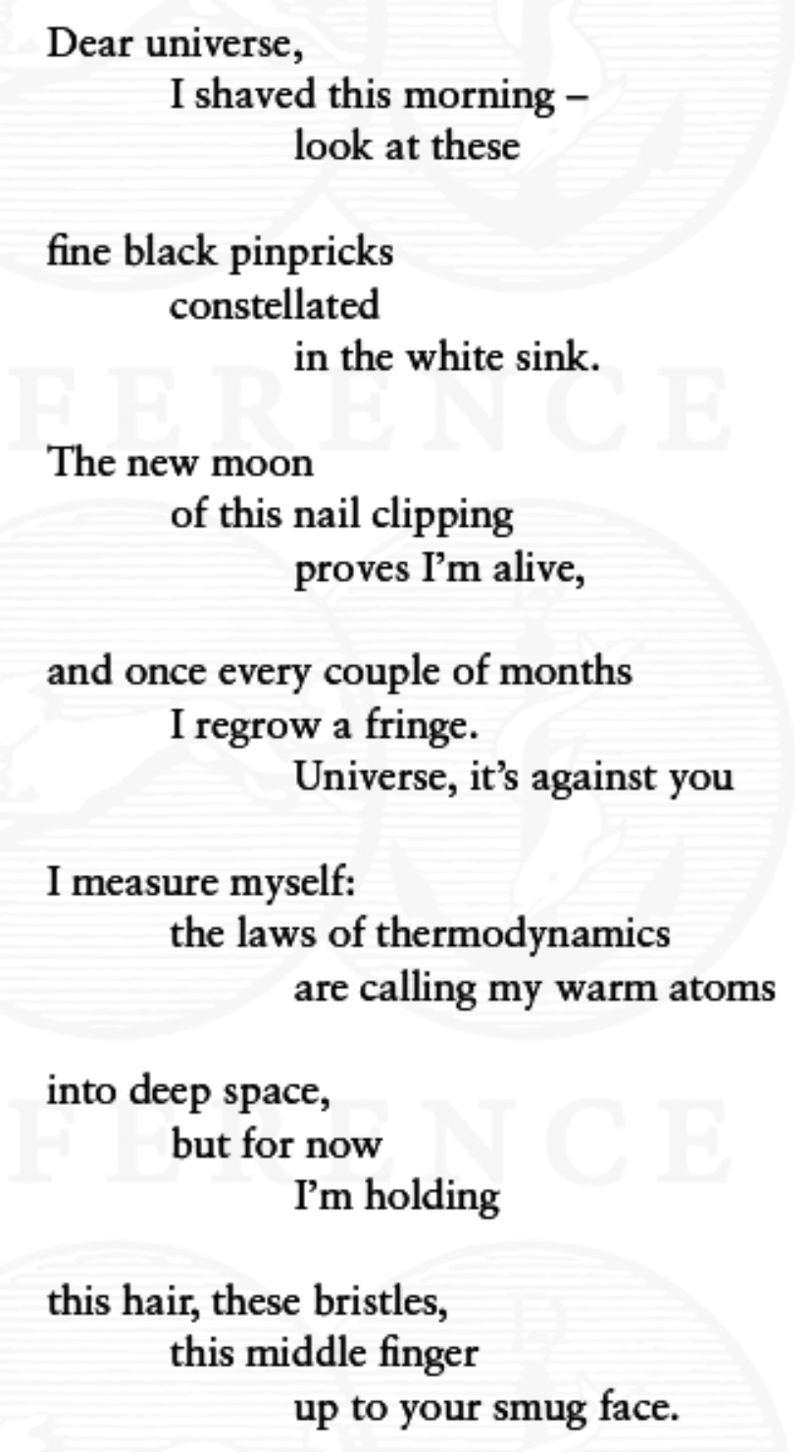

Many of the poems are epistolary: “Dear Universe,” “Dear Nostalgia” (“faithful toady/and arse-kissing best friend”), “Dear Hey Land Cemetery”, “Dear Planet”, “Dear would-be readers”, often with a specific ask, such as paying attention to words, or a direction to move forward, as in “Dear Kirklees Council, I say//plough all you like.” My favourite of these letter poems contains a defiant address to the Universe that gives the middle finger to entropy and death through the simple act of daily grooming:

This poem shows Armitage’s lightness of touch and the assured way he is able to condense so much meaning into the seemingly ordinary space of the shaving bowl with its bristles and nail clippings.

The cemetery takes shape against the changing seasons: “old ice/lending all graves/a pewter-cum-frosted glass-/cum-marquisette frame”, cartoon-themed clouds, heat-marbled air in late May, September’s rain, and early October, “daubed with light” during the height of the Covid-19 epidemic: “those concrete tanks/aren’t Covid-proof liners/as some folk think,”.

A strong thread throughout the book is the impact of climate change. It’s an overt theme at times, leaning into impending apocalypse: “It’s almost/T minus zero/of the Petroleum Era –” or the ongoing unsightly litter of “pound-shop trinkets” on the graves. At times it’s more implicit, in the elegising of trees and the moths who serve as pollinators and whose numbers have declined by a third in Britain over the past fifty years with some sixty species now extinct. The moths make their declining presence felt on night walks in the graveyard, pinned in a case by a collector: “all powder and bristle,/throwing swallowtail shadows/onto your eyelids”. The moths are also metaphors for the writing process, “the wings of moths/are folded pages/of veiled script” moving between the world of the living and the dead: “Because moths/bring word/from the dead.”

The poems in the latter part of the book explore the sudden death of Armitage’s father. These poems are resonant with the many meditations on death, poetry and the cemetery that form the first part of the book but have a greater degree of intimacy, linking the dedicatees of the individual poems, the moths, to the now absent father who is the dedicatee of the book, who continues on as ghostly walking companion. Many of these poems encapsulate the complex pain that comes with losing a parent, an insistent voice in the head, while retaining Armitage’s ever-present humour, even in the most grief-stricken poems: “And a PS: ‘If these/coded notes are all/from your dad, how come//they’re written/in your hand? Will you/never learn, son?’ Armitage is a master at combining the extraordinary pain of grief with the ordinary details of daily life, writing poems in the shed: “the labour and toil/of a hard week’s thinking/and half a poem” or doing maintenance tasks: “Today the poet/is repairing his shed”.

Throughout these poems the personal perspective is beautifully mapped onto the broader pain of loss that the cemetary represents. There is solace in this connection and recognition in these metaphysical and physical spaces of death, that life is prescious, and that we are all deeply connected: “After the sun/the rain, after the rain/the sun,//this is the way of life/till the work/be done.” New Cemetary is a lovely book. It’s gentle and easy-to-read poems feel so light that it’s easy to miss how condensed and resonant they are, but these are words that linger.