Reviewed by Ann Leamon

Reviewed by Ann Leamon

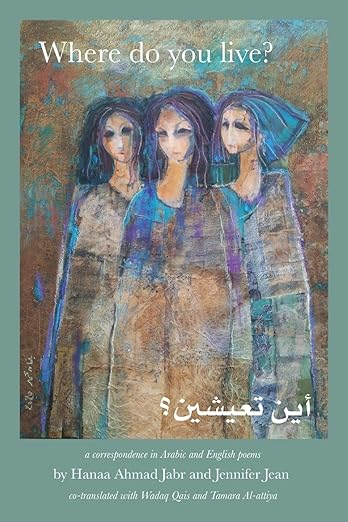

Where do you live?: a correspondence in Arabic and English poems

by Hanaa Ahmad Jabr and Jennifer Jean

co-translated by Wadaq Qais and Tamara Al-attiya

Arrowsmith Press

May 2025, 108 pages, ISBN-13: 979-8990405073

“Where do you live?” We ask it of our new acquaintances and even of ourselves. It’s a curious question, eliciting both a physical address and the metaphysical response of one’s broader context. Provocatively, it’s also the title of a fascinating new collection of poems by two writers, the Iraqi Hanaa Ahmad Jabr and the American Jennifer Jean. The poemsappear in both Arabic and English, co-translated by Wadaq Qais and Tamara Al-attiya.

The first and last poems of the book, both titled “Where do you live?”, reflect the differences between the two poets and their experiences. Jean’s answer to the title question opens the volume:

I should say I live in my body,

in the knowledge

I was fated for—like you said, Hanna [sic]—poetry

Jabr’s reply, the last poem of the book, begins: “I don’t know the name of the first war that birthed me.” She goes on to describe the spiritual desolation of living with this history of destruction from the occupations of her hometown, Mosul, first by the U.S. during its war with Iraq and then by ISIS. Yet both poems conclude with an optimistic vision of the power of art and friendship. Jean says:

You can live forever

in a poem.

Jabr concludes:

Now Jennifer—you may wonder:

‘Who are you? What is your hometown?’

And I’ll answer immediately—with one eye still closed.

We are the two eyes together… forever.

The collection’s twenty-four poems (twelve by each) often respond to one another. Two other sets are paired: “Three Tales” and Jabr’s “Portrait”, which is answered by Jean’s “Regarding Your Poem, ‘Portrait’” Others connect as letters to a friend connect, taking us into each writer’s specific experience. Jean’s own war was the domestic violence of her parents. In “The War I Control,” she writes:

I’m the tail-end of a small war

between a man and a woman—

which is the only iota of war I control.

Jabr describes the impact of war on herself in “Three Tales”:

I talk to you, the other,

about the way each war documented its history

with a hole in my voice

until it became a flute.

This astounding turn of phrase and the beauty from bloodshed startles the reader, who is hurled into the flute-voice of a woman who has lost so much yet sings her grievous history.

Jean’s poems are quintessentially American. She invites Jabr on a tour of Los Angeles in “The Falconers,” referencing lines from a song by The Eagles, a poem by W.B. Yeats, and the movie The Maltese Falcon. “The Horse in Motion,” her last poem in the collection, begins:

My history is film history. We

were both born and bred in California.

In “Response to Your Poem, ‘Portrait’”—her strongest poem in the book—Jean turns her American-ness to strength, describing her unease at Jabr’s words:

Possible responses [to your poem] include:

vague extended apologies for my comfort

or my government, details of dystopian nightmares

But she concludes:

And this is what I can do. Read

your poems. Write my poems. Live between the two.

The originating poem, Jabr’s “Portrait,” is a deeply personal depiction of life in her war-torn country:

He’s coming close, this necromancer…as usual.

[He] declares his win while standing on our carnage…

But a win over what?

Maybe

our distant spark of light!(Oh God, he’s stolen even our sorrow…

Now how do we grieve?!)”

The parenthetical comment—how do we grieve?—forces us to revisit Jabr’s enumeration of losses and wonder how one might respond. How do you grieve when your feelings are crushed? Do we shut down pre-emptively to preserve our sensitivities?

These poems equally apply to the wounds of the Ukraine war and Gaza’s situation. With this context, we can conceive how and why someone might survive those experiences without becoming numb. We must survive to bear witness, as Jabr writes in “Where do you live?”:

Here, I feel my eyes swelling with it all,

carrying The Archives for future generations.

[…]

Oh…I’m here, embracing myself…swelled again

and rising…I think I fell upwards, as usual.

The job of creative individuals, then, is to bear witness to the horrors inflicted by those who would destroy “our distant spark of light.” We must resist and carry our light into the future. Our task, says Where do you live?, is to be constantly raw , constantly attuned to these insults. We must feel them, record them, and keep going.

About the reviewer: Ann Leamon is a multi-genre writer, working in technical finance, poetry, flash non-fiction, reviews, and fiction. Her reviews have appeared in Harvard Review, Arts Fuse, Tupelo Quarterly and Heavy Feather Review; another is forthcoming in Terrain. Her poems have been published in The Lyric, Hole in the Head Review, Midcoast Poetry Journal, Red Eft, and North Dakota Quarterly, among others. River Teeth and MicroLit Almanac have published her flash non-fiction and her personal essays have appeared in The Boston Globe Sunday Magazine and The Washington Post.

Ann holds a bachelor’s degree with honors in German from Dalhousie University/University of King’s College; an MA in Economics from the University of Montana; and an MFA in Poetry from the Bennington Writing Seminars. She lives on the coast of Maine with her husband and their dog, an opinionated Corgi-Lab mix.