Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

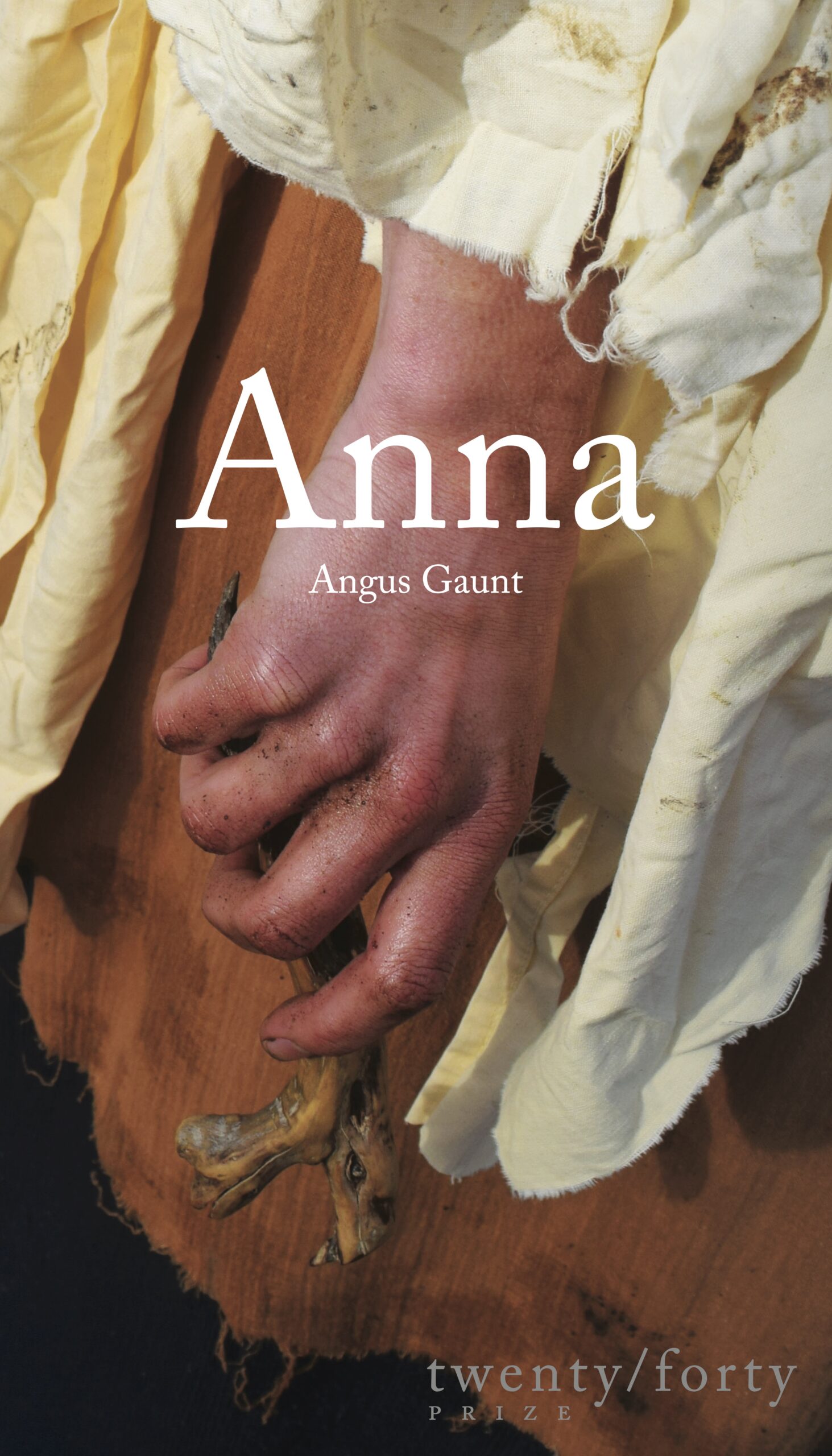

Anna

By Angus Gaunt

Finlay Lloyd

ISBN: 9780645927047, Paperback, Oct 2025, $26aud (on sale for $23.40)

https://finlaylloyd.com/product/anna-angus-gaunt-1/

I’ve been consistently impressed with the Finley Lloyd 20/40 prize winner publications. They are well-designed and easy to carry, slim and lightweight but also attractive with well-contrasted beige matte paper, smooth slip covers with french flaps which hold the page you’re on. These little details make the book a pleasure to hold and read and can slot into most bag spaces so are particularly good for travel, while waiting for an appointment, in a queue, etc. There is no need to ever be without a book. 20/40 refers to the word count – between 20,000 to 40,000 words – novella length for fiction. The length is perfect for a busy modern life, just long enough to allow time for real characterisation and plot development and short enough to finish in one or two sittings.

Anna by Angus Gaunt won this year’s 20/40 Publishing Prize for fiction. The story is told from the point of view of its protagonist, Anna, roughly fifteen years old—neither girl nor woman—who is walking in the woods. We don’t know what woods, what timeframe, what country, or the context. The situation remains nondescript, but we do have some clues. We know that it’s cold, that there was been a war, that Anna has been a prisoner in some kind of labour camp with her family for three years. We also know that it’s the final days of winter. Cold is still very much an issue in the woods, as is hunger. There is a suggestion of wildlife like rabbit and deer, and the possibility of mushrooms and berries, even though there is minimal evidence of these. When the story opens, the war has just ended and everyone in the camp has been set free. Anna has missed the truck departure that her remaining family members were on – we don’t know why – and has to get to the train before it departs, though we don’t know if the families are being sent back home, or if there is even a home for them to go to. There is one other person in the woods with her, a former guard who tells Anna that his name is Yevgeny, a Russian name. Though Yevgeny is not much older than Anna, and keen to befriend her, he is not entirely benign and causes Anna a great deal of pain before disappearing for a bit.

The story remains engaging throughout the book, and Gaunt’s sparse explication is augmented by rich depictions of the natural world that Anna is navigating as she moves further away from the camp:

The forest could be sensed rather than seen. It was like a black wall around her which gave way to the sky at a certain height. There was no cloud. Stars abounded. She concentrated on nothing but the lifting and placing of her feet, which required more effort than sh might have hoped. Herboots were already showing signs that they might not be up to the task. She could feel all of the unevenness of the road surface through the worn soles. (39)

The whole book has a feel of allegory, with the forest taking on an almost animistic feel – you get the sense of this non-human life crackling around Anna – but we also are invested in Anna’s survival. This is partly because Anna’s trajectory is driven forward by her growing survival instinct as she navigates night-time cold, constant hunger, environmental dangers, and the ever-present threat of the people she encounters – some helpful and some less so. Her characterisation is beautifully handled, with her growing self-determination becoming apparent alongside her brief recollections of life before and during her incarceration. These hints of mathematical and musical intelligence, emotional complexity, and an empathy that is undermined by toughness makes her a sympathetic character, particularly against Yvgeny, whose own naivety becomes a contrast as Anna becomes less of a victim, reversing their roles:

How far was it, she demanded to know, to a meaningful place? If there had been one train, why would there not be more? What superior knowledge did he possess that could set them on the right course? She had to put these questions in his language as best she could, which meant edging haphazardly towards a place of mutual understanding where what she said risked losing its scornful undertones. (72)

There is much richness contained in this short book that explores power dynamics, survival, human resourcefulness and frailty with continual dramatic tension and beautiful writing that makes Anna a joy to read even at its most disturbing.