Reviewed by Ester Freider

Reviewed by Ester Freider

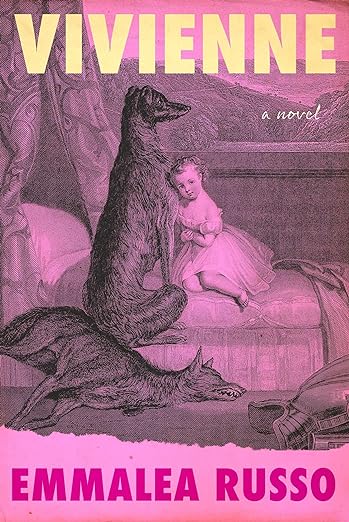

Vivienne

by Emmalea Russo

Arcade Publishing

January 2025, 240 pages, ISBN-13: 978-1648210648

“I am doll parts

Bad skin, doll heart

It stands for ‘knife’

For the rest of my life”

– Hole, “Doll Parts”

Can an artist “turn it off”? Or do they do everything as artists? Emmalea Russo’s firstborn novel, Vivienne, sets the scene with a 50-year old murder tale involving three artists (in our world: two fake and one real). Shortly after a senile Hans Bellmer leaves Wilma Lang for Vivienne Volker, forty years his junior, Wilma throws herself out of her bedroom window. After Hans’ imminent death five years later, Vivienne disappears from the art world to become a seamstress, raising her daughter and keeping mobile from one metropolis to the next. The timeline of Vivienne ensues from the present day, in which 82 year old Vivienne’s fishy legacy resurges due to a proposed inclusion in, and subsequent removal from, a museum group show entitled “Forgotten Surrealist Women”. The novel tramples through interactions between Vivienne, her daughter Velour, her 7-year old granddaughter Vesta, and their various male accessories intercut with the ascent of Vivienne’s five minutes of fame, which metrosexual GALLERY X owner Lars Arden hopes to use for a show that will restore his gallery’s flittish “soul”.

With its triple-V vanguard of weird-girl protagonists, Vivienne is a junkyard cathedral of the female gaze. Velour, sandwiched between Vivienne and Vesta’s drives for disorientation and left (almost peacefully?) dreary from her husband’s fatal drug overdose three years ago, exists in a mundane, house-bound purgatory in which she does “research” on her parents, cares for Vesta and her big dog, Franz, and has half-baked sexual urges towards nearly every man she encounters. Her retired party girl demeanor, and the way in which it is written, is a quaintrelle cross between the main characters from Mary Gaitskill’s Veronica and Otessa Moshfegh’s My Year Of Rest and Relaxation. Velour eats a clot of her period blood and carries ducks across her lawn, observing the stature of her male neighbour. Something about her supine attitude towards life and men mid-life feels deeply un-American. She swaps men around in her head and swats at them halfheartedly as if they are a selection of flowers or shoes:

When Velour wakes for the third time today, she’s face down on her computer and someone with a familiar scent, close and drone-like, pushes hot breath onto her neck. She inhales and groans, spreading her legs… She thinks of Mac, his leather interior and musky cologne… but it’s not Mac behind her. Neither is it Lars, the man in the images. It’s Lou.

Velour’s affair with Lou, a forty-something garbageman and the boyfriend of her mother, is thoughtless and inevitable. It is also one of the only age-appropriate displays of intimacy in the whole novel. The romances of Hans and Vivienne, Vivienne and Lou, Velour and, at the end, Lars and now-grown Vesta, all bear a minimum 25 year age gap that seems to suggest an artistic harvest of youth or innocence. Bellmer’s real biography forms the podgily blatant blueprint for this pattern. As Hannah J. Wetzel notes in her article “Hans Bellmer’s Dolls and the Subversion of the Female Gaze”, his first dolls were spurred into creation by his erotic infatuation with his teenage cousin, Ursula, and meant to be a “partial substitute onto which he could project his desires”. She writes that “Bellmer wrote extensively about his obsession with young girls, making clear the pedophilic implications of his work.” Surrealist artist and writer Unica Zürn, on whom Wilma Lang’s fate is based, was Bellmer’s real-life muse and model in the 50s. In Vivienne, the creepy old man (“OM”, as one fictional forum comment puts it) trope is subverted with Vivienne’s fetish for Lou’s garbage truck work. Herself a reverse magpie of unwanted scrap – one described photo from her youth has her in a rubbish-bag dress – she views her boyfriend’s labour of disposal as an honorable craft. Lou is, perhaps, a reprised Wilma or Unica: an outsider from the art world and its type of people, he feels perpetually that “the women are testing him” or drawing fresh energy from his native link to the rural Pennsylvania town into which their house is semi-sunk.

When Velour finally has sex with Lou, on the cold and dark floor of their unfurnished cellar, it is a half-dream performed next to a large box that contains her father’s doll-sculpture, “The Machine-Gunneress in a State of Grace”. A bare and machinic piece consisting of ball-joint breasts and vulvic blobs, “The Machine-Gunneress” turns the intercourse into an event of reassembly:

She’s amorphous…something like a horse, her mouth reaching for Lou’s back, coffin bone knifing the softer parts of his spine. Lou shoves himself into a hole and Velour buckles, moans…. He blinks and when the creature finally comes into focus, her mouth is a beak.

This transfigurative loss of bodily coherence repeats throughout Vivienne at the height of characters’ sensations. Vesta describes Vivienne’s transition into death as “a bird who became a dog”. The interactions of Vesta and the dog Franz are often simply described as “girl and dog”, like mortar and pestle, or plug and socket. (One could think of that particularly disturbing episode of the anime Full Metal Alchemist: Brotherhood, in which girl and dog are literally combined into one futile novelty for the lawless experimentalists.) Throughout the narrative, there is a sense that events like sex, birth, and death coalesce into artistic hallucinations which violate into the realm of the inhuman. Vivienne, Velour, and Vesta themselves feel like skewed, fragmented reiterations of the former. A three-pronged do-over, in which the longing for a perfect answer to an unknown, empty wound leaves everyone dis-figured and future-less. With Vivienne’s vegetal admittance into the CCC as an “artist”, in which her womb is used for unconscious reproduction, this blur between agglomerate art-making and child-raising is taken to its satiric apogee.

An adult Vesta answers about her experience of her grandmother’s death: ““I was a little kid. And I didn’t know shit. But I knew she’d somehow given her life to art. Or art took her life. Or, that it had nothing much to do with art – whatever that trash can of a word means – and more to do with evil.” Russo’s Vivienne is an off-putting montage that attempts to answer what art has to atone for, or whether it has anything left to offer at all. Women who are childish, nearly opaque, and naturally mildly misandrist are a rare and treasured sighting that I am delighted to have been granted. Vivienne is a mordant, off-centre, and sweetly off-kilter tribute to Surrealism and forgotten artists at large that we’ve been waiting for.

About the reviewer: Ester Freider is a Russian-American writer, digital curator, and ‘creative academic’ residing at the intersection between philosophy and literary studies. She writes autotheory, poetry, and experimental prose; curates and produces live events; creative directs publications; operates as a creative consultant for brands and galleries; makes performance art on the internet. She lives and works in London.