Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

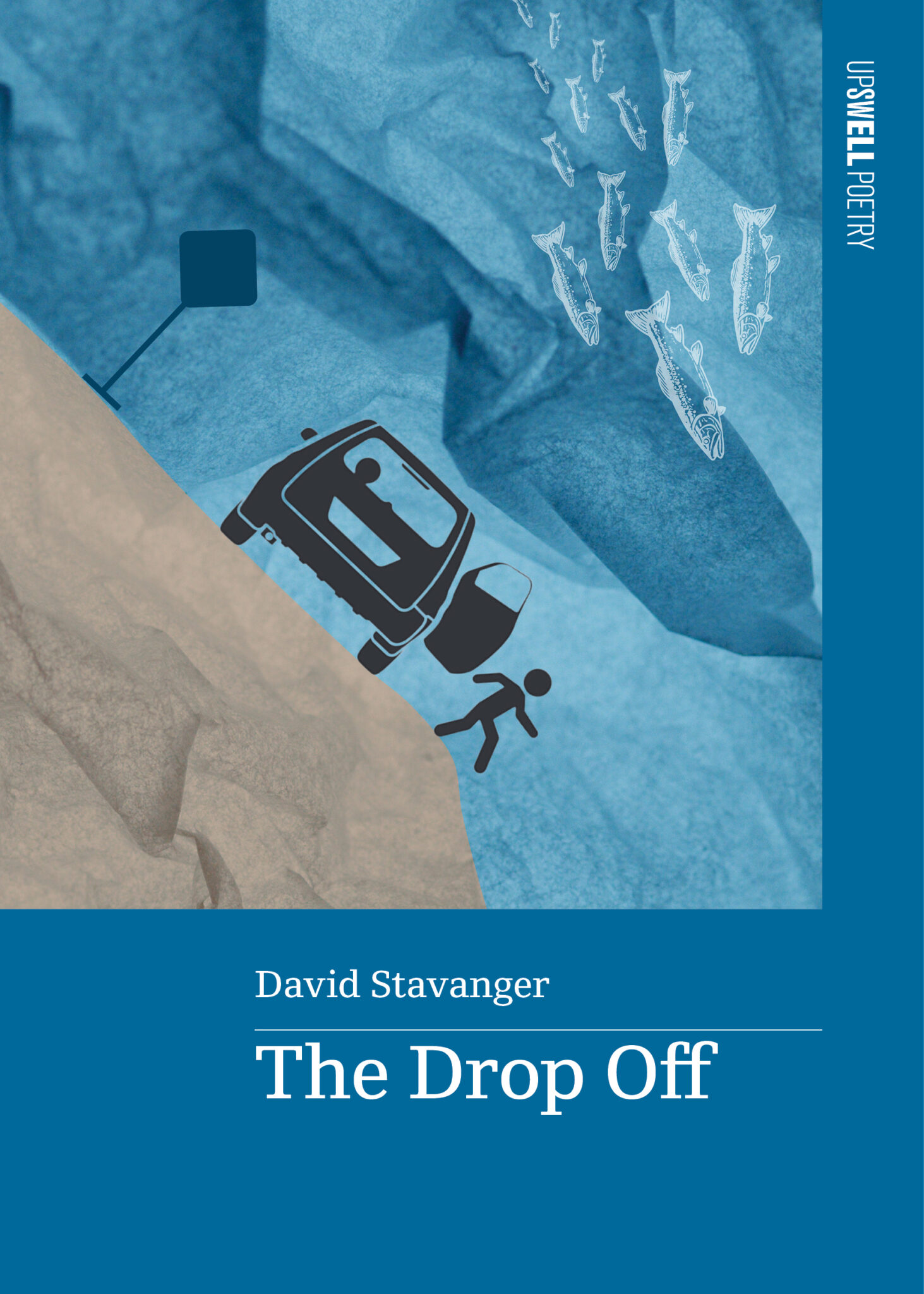

The Drop Off

By David Stavanger

Upswell Publishing

116pages, $24.99, ISBN: 978-0-6459840-8-8

David Stavanger’s third full collection, The Drop Off, manages a perfect balance between irony and intimacy, There are often external referents–well-known artwork, found-text excerpts from newspapers, satirical columns, public speeches, and online forums, coupled with the domestic. The book pivots around parenting a child, post-divorce. Saul features throughout the book, as subject, object, even as creator in a joint poem. The slippage between loss/desire and the pulling back into the self are part of what makes this book so powerful. These dichotomies feel true to experience. This is epitomised in the first poem, which is one of two poems in the collection that reference the conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp, himself an avid player of chess:

One day we’ll play

without consent order

on the outskirts of Paris (“The Chess Game”)

Duchamp was a polarising figure, known for his readymades like Fountain, a porcelain urinal signed “R. Mutt” which evidence suggests wasn’t even Duchamp’s but rather the work of the outrageous Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. The reference alone creates a layer of association that extends what otherwise be a tender moment between a father and child into the world of Dadaism with its play, mirrored in the chess game and shifting roles of the players:

Sometimes I let him win, sometimes he wins.

We hunch over, contemplating next moves.

This complexity is further extended by a poem that appears later in the collection titled “stair/case”, a response to a George Karger’s photograph of Marcel Duchamp on a staircase designed to mirror Duchamp’s most famous painting “Nude Descending a Staircase”.

I stand to strike blows for space

cast a shadow-like picture of

the plastic duration of desire

without trying to argue [post-coitus]

who is the child, who is the last step

This poem is roughly the same length as “The Chess Game” and these poems, initially published together, link across the book by the Duchamp connection. This one is right aligned, and between these layers of visual association and the structural mirroring of these poems, we are made to think about the way a child might inhabit a space like the descending nude, in transition and fixed.

The poems in this collection play with neologisms like Gyneth Paltrow’s “conscious uncoupling”, the ‘Experience Economy’ and “non-fungible commodities” using a range of poetic devices from alliteration, anaphora, synesthesia and repetition, inversions, dialogue, typographical and concrete effects, redaction, even a dad bingo game. The Drop Off takes these notions of play, irreverence and art, and utilises the tools of poetry – redaction and silences, puns, the language of public discourse, rhythm and structure to lead the reader, almost by stealth, into sudden moments of intense vulnerability:

Your arrival I emerge with connective tissue.

In that nursery of strange wet babies, considering flight

from maternity’s wing. Monitoring breath’s escape,

units of dependency measured in the phrases of a lullaby. (“I’ve been thinking about your birth lately”)

There’s a rhythmic cadence that acts as a facia through the book, binding the poems to one another and creating a layer of non-linguistic meaning. Nowhere is this more prevalent than in the title poem, a multi-page piece that begins by immediately throwing the reader off-guard by starting at number 3 rather than number 1. This poem works beautifully across a time spectrum that follows the growth of a child from age three to adulthood: “You are dropping off your child for the final time”. As structurally playful as this sequence is, it also has a narrative arc, a coming-of-age that once again hearkens back to Duchamp’s staircase – a moment of motion and becoming charged with loss, guilt, and above all, a deep and slightly astonished, love:

the catapult of time catches you unaware.

When they walk up the drive, fractured

childhoods pass in the rear view mirror,

as concrete as pulling away from the gutter and kerb. (“The Drop Off”)

Not all of the poems in The Drop Off are parenting poems. Other poems explore aging, mental and physical health, the destructive path of modern-day capitalism, climate change, the housing crisis and a continual struggle against constraints and unhealthy societal norms. Bodies are the focal point of the struggle, and these poems are no less intimate in the way they bring us, via the slipstream of humour and sometimes official language, into the heart. For example, one poem, “Cystometrogram”, takes us right into the body:

…For the sake of urodynamics,

I am filled and then emptied

like a fish stranded in a bathtub

hooked by the tip, slack in their soaped hands.

Later in the book, a poetry collaboration with Saul called “FIfteen ways to be erased” tells the story of school-day bullying from dual generational perspectives connecting across 30 years. The sections ‘talk’ to one another, connections coming alive through the comparison of diary entries, coping notes, the blurring of personal pronouns, school letters with the name redacted so it could be one person or the other. The poem is deeply moving, gathering the reader into the collective “we” so that we are present at the moment of assault. Like many of the poems in this book, the work moves very smoothly, almost imperceptibly between anger: “Like to see that guidance de-escalate a fist at the point it regrades a face. Like to know the last time someone reduced him to a noun.” and philosophic contemplation:

The word ‘bully’ likely evolved in the mid-sixteenth century from the Middle Dutch word Boele, which loosely translates as ‘lover’. A term of endearment, a familiar form of address to an intimate friend.

The final poem in the collection, “Montage”, is, in some ways, another collaboration. These are lines for a film production which I believe is later produced by Saul. This works visually, with strong, and often surreal/dreamlike and humorous imagery: “An asteroid hits Saul’s desk (high contrast lighting). They slowly enter the crater.” It feels like a fitting finale for the book, almost a handover of the creative practice – a reckoning with the self, indeed compressing time:

David is holding the compression of time. Both hands are closed and open. Stills are spilling from his mouth (positive and negative.) There are no other props or cast nearby.

The Drop Off is a terrific book. The way in which the poetry moves easily between acerbic even, at times, caustic, wit to a self-deprecating and open vulnerability cuts through any readerly defences, making this a powerful and rewarding read.