Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

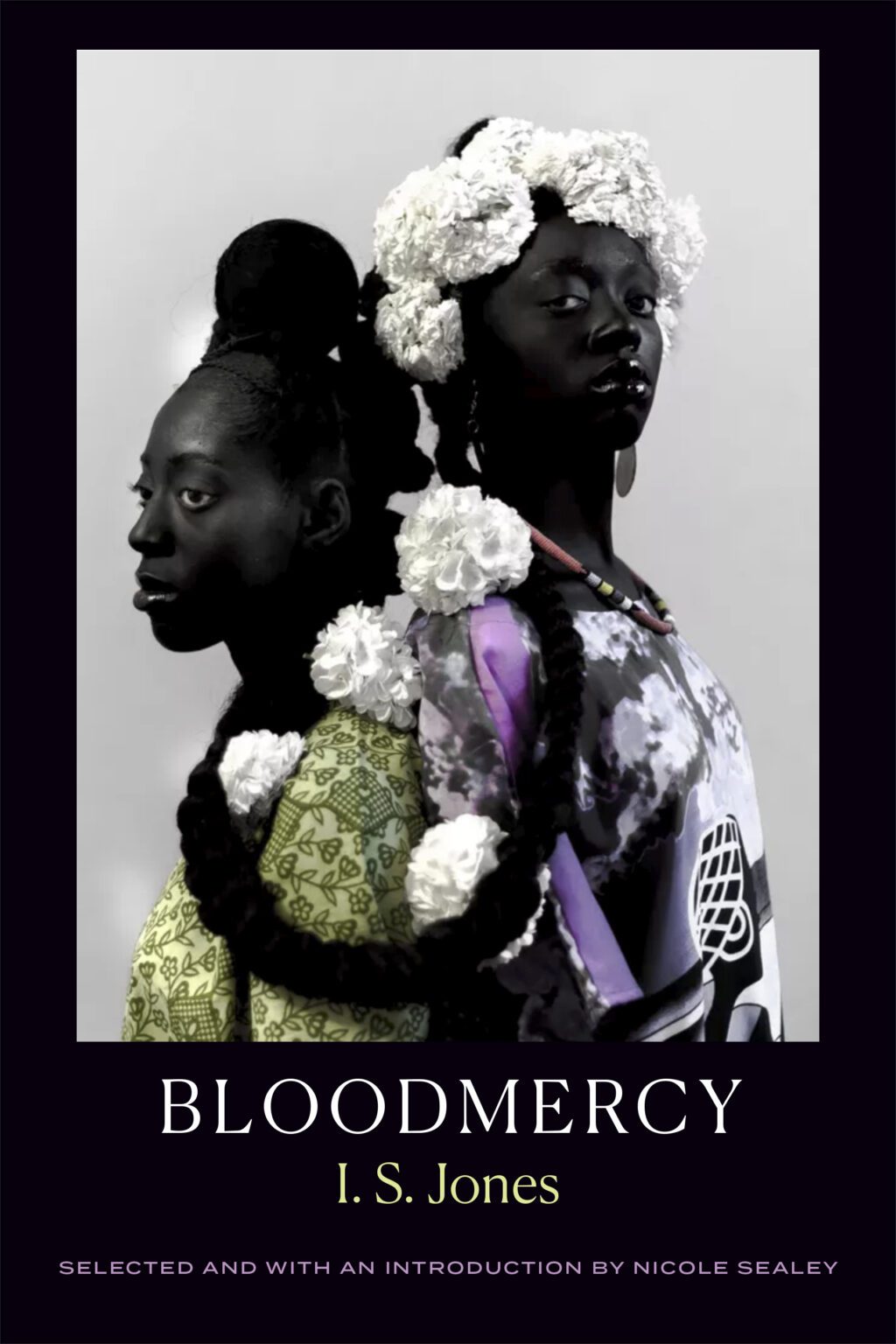

Bloodmercy

by I.S. Jones

Copper Canyon Press

$16.00usd, 80 pages, Sept 2025, ISBN: 979-8-98758-523-8, Paperback

I.S. Jones lyrically re-imagines the first dysfunctional family in her debut collection, Bloodmercy. Only, in this version, Cain and Abel are sisters. Eve is transgressive and Adam is a brute. Though it misses the point to describe Bloodmercy as a “re-telling” of the Adam and Eve story, it’s helpful to remind ourselves of the high points of the Biblical narrative. Adam and Eve, the first humans, are living an idyllic life in the Garden of Eden, their only restriction is not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. A serpent convinces Eve to eat the fruit from the forbidden tree, for which they are expelled from the garden. God spells out the consequences of their disobedience. For Eve, it means the pain of childbirth and subordination to her husband. Outside the garden, they have many children, but principally Cain and Abel. Cain kills Abel out of jealousy when God prefers Abel’s offering to his, thus becoming the first murderer.

Yet the point of Jones’s poems is mercy. What is it? Who merits it? Who grants it? Why? How is it manifested? She writes in “Hands of the Field,” a poem in Cain’s voice: “My mother calls it backtalk / when I say, ‘God still needs people to forgive.’”

The collection opens on a sort of prelude, also in Cain’s voice, “After the Offering Ritual, Cain Carries Abel Home.” It begins: “Violence is a failure of communication.” It was an offering ritual that caused Cain’s jealousy to overcome him and murder Abel. Here, Cain does not slay her sister but tries to soothe Abel after they kill the goat. “We have blood and dirt

together they make God. And what does mercy look like

between humans? A sister reaching to lift a sister

from the ground. When I say a love that will end us,

I mean ‘mercy.’ Remember, I offered you my hand once.

Push me away if you like.

Jones’s poems are all told from the perspective of either Cain, Abel, or Eve. Bloodmercy is made up of six parts, including Cain’s opening prelude. Part two is mainly in the voice of Cain, except for one poem in Eve’s voice, “Contempt Towards Eden,” which begins, “Milton gets the tale about me wrong. Paradise is boring.” Part three contains ten poems, all in Abel’s voice. Part four switches between Cain and Abel, and Eve has one poem, “First Drought.” Her contempt is still evident: “when i could suffer no more,” she says to God (Baba), “there You were, blistering with perfection.” She goes on to throw shade on Adam, “confess it would be alright if husband never returned. / Ideal even.” By all accounts – Cain’s, Abel’s and Eve’s – Adam is a real bastard, violent and touchy, an authoritarian prick. Part five contains two poems, both in Eve’s voice, “Eve” and “Eve onto Lilith,” in which she addresses Adam’s first wife, as she is described in Jewish folklore, whom Adam originally banished from Eden for refusing to obey him. “At night he fucks me so hard I bleed,” Eve tells Lilith, referring to Adam. Pregnant, Eve pleads with Lilith. The poem ends:

God tells me once the miracle comes, we have to leave Eden.

He doesn’t explain what ‘miracle’ means,but says ‘punishment’ means ‘deliverance.’ Sister, I’m scared.

I don’t understand what’s growing inside me.Days uncount themselves. My body, gorged & overripe.

God tells me this is my gift instead of death.That I would create life the only way a human can.

I’ve never flinched before a man & I don’t intend to start now.Your body is a spell I summon from dust.

Lilith, deliver me.

Part six is the final poem in the collection, a sort of coda in the voice of Abel, titled “Bloodmercy.” The penultimate poem of Part two is also called “Bloodmercy,” this time in Cain’s voice.

Bloodmercy, indeed, is mainly about the sisters, Cain and Abel, as they grow into womanhood. “Daddy’s Girl,” in Cain’s voice, starts, “Lord forgive me, I am my father’s child: / cunning and arrogant with beauty.” She goes on, “I am 8

and can only see my mother for her gender—

exhausted to a numb, wounded, bitter

to the touch. The feminine urge to be

my father’s best boi, I boy’d better

the other boys—peed standing up,

won every game of ‘nut check’, shot

my first kill by 10…

The girls grow into womanhood in Abel’s “Field Notes in the Final Days of Girlhood”; “Mark of Cain” again refers to menstruation as God’s punishment. (“Baba said this is my gift instead of death: / The Mark of Cain.”). “Self-Portrait of the Blk Girl Becoming the Beast Everyone Thought She Was” (Cain) further develops the theme. Cain’s “Psalm for the Fast Girls” also negotiates the interaction with boys, growing up. “Girls like me are born armored against ‘cunt,’ against ‘hoe,’ ‘whore’ too.”

In “Cain in the Peopleless Kingdom,” Cain alludes to her father’s violence, “what Adam does to my mother, dragging her / by the throat into the bedroom.” In Cain’s version of “Bloodmercy” she laments to her sister that she “wanted to deliver you / from cruelty & gave you my own instead” and laments further, “Now you keep secrets from me.” When she notices Abel is bleeding, she pricks her own skin and mingles her blood with her sister’s. “My blood meeting

yours to become “cainabel.” My name eating yours to become

“cannibal.” Mercy at your still body becomes “claimable.”

Call it “grace” or “pity,” you my ancestor, my wife, I should

have ended you when the stakes were lower. Wound of my wound,

immutable bond, my heart unknowable from yours becomes “chainable.”

Clarity arrives as patient light. No matter what wind will drive us apart,

you’ll never leave me.

This empathetic sense of mercy is answered by her sister Abel in the final poem, also called “Bloodmercy.” Like Cain, Abel implicitly identifies with her sister: “I trip & you twist your ankle; / loneliness clouds your mind; the pain invades my dreams.” The poem – the book – ends beautifully on her speech: “you, my child

guardian, ancestor, my husband & wife: I do

carry you with me all my days & even when the maggots

will make tender work of our flesh.

I close my eyes to see you with my heart, I close my heart

to see you with The Spirit.

What we knew to be ‘love’, was more habit than conviction.

To live, I remove the yoke bearing ‘sister’

& leave you here. Nostalgia & origin are two points

that come to meet again,

the singular braid binding our fates—

fox to rabbit, myth to song; mercy to sister.

Bloodmercy is very much about female empowerment. Mercy is at its heart. Poems like “Sister’s Keeper” (Cain) and “Between Grace and Merc” (Abel) likewise develop this theme. I.S. Jones is an important new voice in poetry.

About the reviewer: Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore. His poetry collection, A Magician Among the Spirits, poems about Harry Houdini, is a 2022 Blue Light Press Poetry winner. A collection of poems and flash called See What I Mean? was recently published by Kelsay Books, and another collection of persona poems and dramatic monologues involving burlesque stars, The Trapeze of Your Flesh, was just published by BlazeVOX Books.