Reviewed by Justin Goodman

Reviewed by Justin Goodman

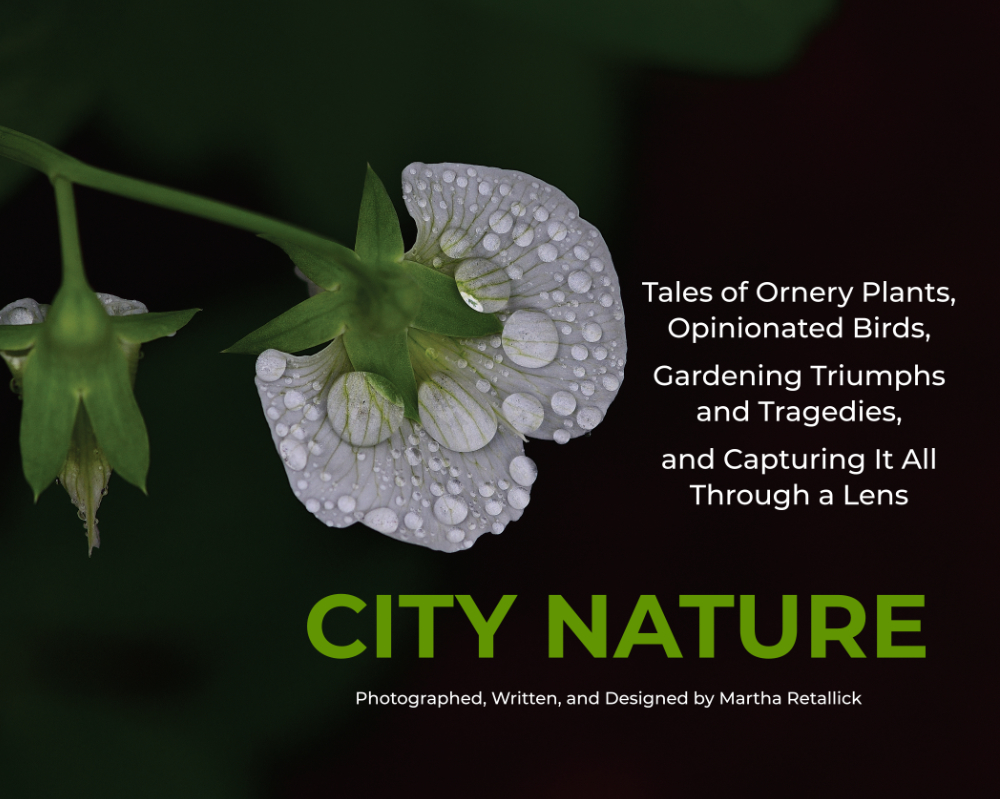

City Nature

Tales of Ornery Plants, Opinionated Birds, Gardening Triumphs and Tragedies, and Capturing It All Through A Lens

by Martha Retallick

Western Sky Communications

ISBN: 9798986857701, November 2024, 106 pages, hardcover, $99.95

There’s a single word that captures Martha Retallick’s self-published “much more than a nature-themed coffee table book,” City Nature. It can be found in her December 4, 2020 blog post. There, she links to the exhibition catalog that she shared for a then-recent Open Studio Tour held by the Arts Foundation for Tucson and Southern Arizona. Composed of nature, bicycling, and construction photography, the catalog is titled A Tour of my Eclecticism as a Photographer and Writer. “Eclecticism” is the word. In this book directing “city dweller[s]” who may feel they’re “’in here’ and nature is somewhere ‘out there’” to think of the titular city nature as “your personal garden (landscape),” Retallick fits in several recipes, bits of memoir, Arizona-specific gardening advice, bird facts, amidst the photography. Her most admirable quality as a writer is this jerky-like tenacity to share, in text as in life. Retallick love wearing multiple hats – from blog posts “micro-scale urban farmer” and “publishing entrepreneur,” while in this book she is designer-writer-photographer. At times this gumption, however, seems like an animal whose tail erases its own footprints. It’s hard to keep track; you scratch your head wondering what animal could have made these painterly strides; you wonder if anyone else knows about this cryptid.

To be clear, City Nature is a loved-over book. Retallick’s “Blogging My Book” posts document the nearly two year process of publishing it, and there’s an undeniable earnestness to how she explores the three themes she signposts at the start: “Nature and the Built Environment,” “Nature Nourishes,” and “Nature Delights.” After a lengthy introduction describing what brought her to this moment, we hear about how she renovated her house and added a cistern to harvest water with the help of her local co-op, learned which plants grew best in the Tucson climate (detailing the mesquite collecting process since “15-minute mesquite cookies” is one of the recipes), and, finally, her various little interactions with trying to capture bird and plant life on camera. While the photos themselves tend towards inexpressive and functional (although the chiaroscuro on a Texas ranger bush going through “one more round of flowering” before the season ends is, fittingly, elegiac), that’s not itself bad. You end up staying for Retallick’s storytelling anyway, its folksy directness. A Tucsonan might appreciate the tips, tricks, and knowing how to identify the haunted-looking bird on the fence as a curve-billed thrasher, but for city dwellers not cohabitating with desert dweller birds, City Nature is a vague invitation.

The book’s palette hints at the limitations of the eclecticism. Conversational text against eggshell, nature descriptions (and recipes) against pale green, birds against puce (but only pages 62 and 64), hesperaloe blooms on page 73 with a gray border (which Ulisses Alfredo Castillo Soto shares on page 84). While the colors synergize nicely, their rationale is opaque. Such is the same with the way each genre City Nature adopts functions physically in the world. Coffee table books are stationary and ornamental; cookbooks, while aesthetic, are functional, to lug into the kitchen with its messiness; memoirs are ideal for traveling with, an entire life read at your pace; blogs, casual and serial, are anticipated and read live. City Nature, trying to be “much more than,” ends up as an idealized jumble. Within it is the logic of the good value proposition, of a product striving to earn its cost. It leaves the reader in an uneasy contradiction – the invitation includes the suggestion that “If you want to combat climate change, plant a tree and give it a hearty ‘thank you,’” but it’s precisely the individualization and marketization of collective life that led to our climate changed world. You almost long for it to simply be good at what it is, rather than a vehicle of infinite potential that haunts the fantasies of the entrepreneurial imagination.

Retallick’s self-published 1992 travelogue, Discovering America, is a contrast. Between 1980 and 1992 Retallick set herself the goal, fresh from college, to bike through every state. As much about discovering the meaning of home as much as America, the book is a straightforward story of a young cycletourist’s encounters with strangers (and herself as a stranger through them) only occasionally interrupted by plugs for cycling products and services between chapters. While the plugs could weigh on the book like business proposals, Discovering America’s singular pathway and emphasis on self-discovery through the collective life makes such proposals feel like ways to participate in that collective. It asks whose America and answers ours. City Nature leads one to ask whose city and whose nature, answering mine. It’s a very American contradiction which Retallick intuits based on the history of these books. Discovering America was preceded by the abbreviated Ride Over The Mountain: the individual achievement transforms into the experience of difference. City Nature was preceded by a similar photobook, Urban Oasis: the escape from the city becomes the city. As a fellow city dweller, I share the sorrow of being at a remove from the green sensation of nature. The joy of the city, however, is the collective life as natural.

And Retallick understands this too. She often mentions her co-op that helped install her cistern and her grandmother’s victory garden. The conflation of “personal garden (landscape),” of the individual life and the collective one, is precisely the felt absence in City Nature. Victory gardens had a purposeful, singular aim – replace flowers for food for the collective good during WWII. After the war, the crop were allowed to rot so flowers could bloom. In her Cultivating Victory, Cecilia Gowdy-Wygant points to a 21st century invocation of victory gardens as a turn from “aid[ing] the needy” to “promot[ing] individual Americans’ own sense of security and stability.” From the landscape which exceeds us, to the gardening we hide in. City Nature surely does a service for Tucson, which appears as a joyous locale (if maybe too hot for this city dweller). But for cities generally? The best moments come from the struggle against solitude; with Retallick, it’s the trials-and-errors of learning to “think like water” with her co-op in a drought-filled era, of upcycling a gifted chandelier into a vine climbing gym and a sun-shaking pendant collage. Not the “much more” of products, but the “much more” of the lived-in; we are nature too. The struggle against solitude is the discovery of home, and it glints like pendants. We hope to discover Retallick’s in its fullness one day.

About the reviewer: Justin D Goodman (they/them) is a writer based in Brooklyn, NY and a member of the New Haven Writers’ Group. Their work has been published, among other places, in Cleaver Magazine, Prospectus, and Prairie Schooner. You can find more of their work at JustinDGoodman.com