Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

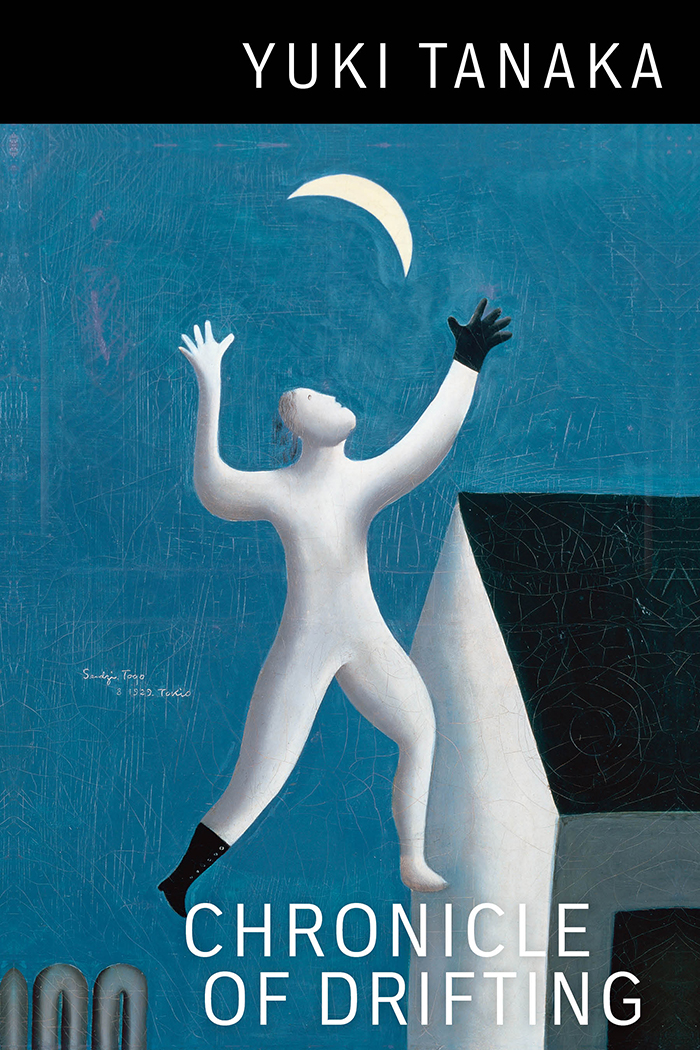

Chronicle of Drifting

by Yuki Tanaka

Copper Canyon Press

July 2025, $17.00, 80 pages, ISBN: 978-1-55659-705-3

“I can’t invite anyone into my head because it is not comfortable,” the speaker in one of the sections of the “Chronicle of Drifting” prose poems says. He’s in a museum observing a hermit crab migrating from shell to shell. The speaker is a teacher who has just been in a faculty meeting “about punctuation and the aesthetics of powerpoint.” It sounds ironic, and maybe it is, but Yuki Tanaka has invited us all into his head in this magical collection of writing, part prose, mostly verse.

Divided into four sections, three of which start with epigraphs from the eighth-century Manyoshu, the oldest anthology of Japanese poetry, the poems all have the surreal quality of a suspension of cause-effect and a fairy-tale atmosphere in which mermaids exist and cats talk. The poem, “The Village of the Mermaids” begins:

My cat said, “Your thick green robe tastes of salt,”

and licked a satin curtain

I have learned to sit still on a chair

in front of my house and remember our home,

where I wore a necklace of sea-foam

some called a lovely snare.

It’s a poem from the mermaid’s perspective. A man with a bowler hat that he tips “like a magician,” tells the mermaids that “There is a spell in every seashell.” It all feels like a charmed folktale, but the underlying vibe is a kind of dislocation or alienation.

In the “Chronicle of Drifting” section, fifteen short prose pieces which appear to be the diary of a man who has moved to Tokyo from the provinces, the protagonist is always on the move, a classic flâneur, noticing everything around him. (“Moving to Tokyo has changed my mindset—never stop, never wait. In the mountains, I could stand in the rain, like a parsnip waiting to be pulled up by the hair.”) “When I am not walking, I liquefy,” he writes.

The flâneur tells us, ”I’m reading a book about thirteen geisha girls who boarded a steamer to America to attend the 1901 World’s Fair in St. Louis, as part of the Japanese exhibit.”

Indeed, the second section of Chronicle of Drifting contains three poems – “Exhibition of Desire,” “The Empire of Light,” “The Body in Fragments” – that are from the geishas’ point of view. It’s a strange experience, the women displayed as freaks or sirens. “The Empire of Light” begins:

We are asked to stand at the pond. A sudden light

drowns us. Four empty turtles filled with flowers.

We use our bodies to grasp a foreign tongue.

Red-eyed fingers, porcelain skin, dark eyelashes

that never fall. Come, we say in unison, and they come

as ants gather around a slowly loosening sugar cube.

As the title suggest, the general drift of these poems reflects a rootlessness, a restlessness. The epigraph to the fourth part comes from the ancient poet Sano No Chigami No Otome, who was a low-ranking female palace attendant and wrote love poems, reads: “You have departed on a long road.” Tanaka’s multi-part poem from this section, “Discourse on Vanishing,” concludes with the line: “This is not the end of the broken world.” And yet, the world does appear to be broken and negotiating its brokenness is the challenge.

Tanaka, who teaches literature at Hosei University in Tokyo, teases out the etymologies of Japanese words throughout. “Two words for ‘heart.’ Kokoro means heart in a moral, spiritual sense,” he writes in one of the “Chronicles of Drifting” prose fragments, “it never refers to the organ. Shinzo, it always does.” The geisha poem, “The Body in Fragments,” likewise considers English and Japanese words, from the geisha’s perspective: mizu and matsu (“water” and “wait”), and marzipan, maze, meteor, marsh. It feels instructive, as if we were in a classroom.

Perhaps the poem “One Arm” best captures the overall mood of this colledtion. It’s a poem that involves a detached arm. Not quite like Gogol’s nose, the arm speaks or has an impulse toward speech. It’s clearly disconnected from the whole. The poem ends with the introduction of a mysterious character absent from the seven preceding stanzas:

The first sentence: “I can let you have

one of my arms for the night.”

She tears her arm off

and places it on my knee.

Similarly, “Aubade” involves a grandfather’s kneecap used as a drinking cup for sipping sake. A woman and her son detach the kneecap and wash it a stream. The poem ends:

Funny he seems more alive now,

this trembling bone under the cold water.

Full of these curious images of estrangement and separation, Yuki Tanaka’s Chronicle of Drifting, at once surreal and folkloric, charms the reader with a dreamlike urgency. As the final poem in the collection, “Evidence of Nocturne,” concludes so eloquently:

This pile of wood wished to be a stairway

but couldn’t. Will you pretend to climb it.

Yuki Tanaka’s invitation into his head is a mind-blowing adventure, like a seeing the world through Lewis Carroll’s looking-glass.

About the reviewer: Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore. His poetry collection, A Magician Among the Spirits, poems about Harry Houdini, is a 2022 Blue Light Press Poetry winner. A collection of poems and flash called See What I Mean? was recently published by Kelsay Books, and another collection of persona poems and dramatic monologues involving burlesque stars, The Trapeze of Your Flesh, was just published by BlazeVOX Books.