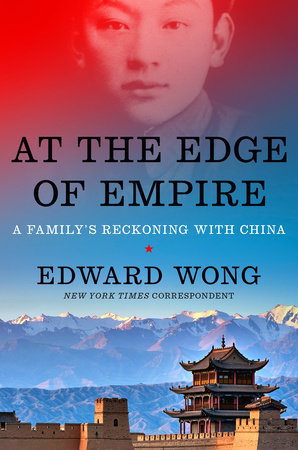

At the Edge of Empire: A Family’s Reckoning with China

Edward Wong

Viking

June 2024, $32.00, ISBN: 9781984877406, Hardcover

We come into a world already run amok with history, and we are, in effect, its captives. This behooves us to learn it, for purposes of disentanglement or enlightenment. And to share, to sort it out, for the benefit of those who follow, as well as those whose connections might be less direct. This is precisely what the award-winning New York Times correspondent, Edward Wong, does in his book titled At the Edge of Empire. While his subtitle speaks of his family’s “reckoning” with China, this book also represents the author’s reckoning with not only his family’s history but that of his sources, his reckoning with multifarious and important writers and scholars of Chinese history and culture. Wong braids numerous story strands, of both his family—focusing especially on his father’s story—and the nation of his ancestors, namely China, an incredibly complex and startling history with its “cycles of war and dissolution and reunification.” His scholarship underpins his journalistic on-the-ground experiences covering such events as the ethnic clashes in Xinjiang, where his father, years before, had been stationed, and the protests in post-British-ruled Hong-Kong, where his father’s family was forced to leave in 1941, at the start of Japanese occupation.

His book comes greatly informed by both Wong’s impressive understanding, extensive study, and knowledge of China, past and present, obtained by a series of interviews, his education, his travels, and his experiences by virtue of his former status as New York Times bureau chief in Beijing. The interviews in question are those of his father, a first-hand source. If chapter notes and an index endow the work with a scholarly precision, nothing can overwhelm the warmth and intimacy of a narrative that is largely informed by interviews of father by son. The reader is in the hands of a writer and scholar whose last twenty years have been dedicated, it would seem, to gathering and sorting material to offer the reader a powerful view into a highly complex culture and nation. Motivated, it would seem, by a profound interest of his own, Wong writes, as it has been noted elsewhere, almost as filial duty to a father whose loyalty to his country was betrayed by its leaders.

It has been said that the three criteria for a good story are: conflict, crisis, resolution—and while Wong’s book offers a large and seamless grounding in the history and geography that give rise to it—what drives this book is the plight of Wong’s father, and the futility of his mission to become a soldier in the AirForce of Mao Zedong to take part in what we in the US remember as the Korean War portrayed by Mao as an effort by the monolithic US to colonize Asia. We are taken into the mind of the young Communist-leaning Yook Kearn Wong (whose name in Chinese means “fertile and strong”), younger brother of Sam Wong, who unlike the author’s father, elected to undertake his schooling in the US. Rather than following in his brother’s footsteps, Yook Kearn Wong chose to travel north to Beijing for his education, hoping that it would lead to an important position in the military, little realizing that the sheer fact of his brother’s immigration to the US would effectively put a thorn into that quest at every turn.

What commands the reader’s attention, besides the wealth of information presented so fluidly, with prose tethered to setting and alive with well-measured description, and with a good balance of scene and summary, are the family stories, and most specifically, the writer’s father’s, journey—which engages like fiction—juxtaposed against his, the author’s, journey to document this story. The lives of Wong’s family are very much directly embroiled in the historical event with which he begins the book, namely the occupation of Hong Kong by Japan, in December 1941.

It’s that last fact that encouraged me to review the book. I happen to be married to a Wong and some of my fiction has been inspired by my husband’s family stories where there is a similar starting point—similar relationships between Hong Kong and the villages in the Guangdong Province where the dialect of Taishanese is spoken.

I had hoped Edward Wong’s book might give me a greater understanding of my husband’s and my children’s heritage.

And this book has more than delivered. And I appreciated the storytelling—the descriptions of setting, of the various dishes of the various regions of China, his close study of the cultural contours, the more mundane moments of his travels, that he offers up in scenes, utilizing the strategies of fiction, so the reader can imagine his various meals, the imagery of the geography, the clothing, identifying the languages spoken, not to mention the way he built the plot, utilizing the techniques of gaps and delays, so that even though I knew Yook Kearn Wong would find his way to the US, I would not know the specific circumstances until it was played out until the last detail—and I would be hungry for those details.

I am someone who generally learned my European history by way of Shakespeare, Hugo, and Dickens and the like. I learned my Russian history by way of Tolstoy, and I’d learned what I know of Chinese history by way of such authors as Malraux, Amy Tan, Maxine Hong Kingston, and Anchee Min. As for African and South American history, I admit I read across the genres—but generally speaking, even when it came to understanding US history, I understood it through storytelling—fiction. It’s only been very recently that I reviewed a book of civil war history, another book I thought was exemplary—and another book that embodied the history with family stories, that really gave voice to this history, and in fact re-voiced it.

Wong breaks chronology in his narrative by alternating his more current tale of the documentation with his father’s story—a structure that serves him well, allowing for the layering of information, organizing the enormity of his material, with commentary, that embraces a thousand years of history, and placing his father’s story within a modern context.

Wong’s documentation bespeaks the depth and breadth of the author’s research; his is an incredibly dramatic approach, imbuing history with story, embedding a personal narrative within the narrative of nation, not to mention transnational narratives. It is an unimaginable undertaking. The author himself has had numerous occasions to travel to various regions of China, his mission is two-fold, both journalistic in nature, as a correspondent for the New York Times, and to document his father’s journey. He notes how things have changed, both by way of the geography and the population. In 2008, he is in Beijing covering the Olympics when an American graduate student shares what he witnessed of the clash between so-called Uyghur separatists and the police. Wong returns, recalling previous visits, when he had felt the tension, noting that China exercises “regulation” over Islam, and each of the “five official religions of China” which also include “Buddhism, Daoism, Protestantism, and Catholicism.”

What is in a Wong. For me the name of Wong is familial. It’s the last name of my children, of my husband; it’s the name I have used and may legally use, but generally I don’t.

For my husband’s family it’s the name that came by way of purchase, the name that enabled my father and mother-in-law to leave China at a perilous time of their lives.

For Edward Wong, it is name with a significant history. According to the writer’s uncle, his father’s brother Sam, who himself had written up a family history, “the earliest known parts of the lineage date back more than two millennia, to the Kingdom of Wong, in territory south of the Yellow River valley the cradle of an early Chinese civilization.”

Wong writes: “Migration became a constant throughout the Wong lineage. A family ancestor, Qiaoshan…ordered twenty-one sons to settle away from their hometown around the start of the Song dynasty, a time of great social and economic transformation between the tenth and thirteenth centuries.”

For me, this comes as new information, really challenging the idea of the east as “exotic.”

Among the elder Wong’s story about the power of the individual and the state are many stories. It’s a story about nationalism, about personalities and histories of those in power, those who wish to assume power, those who believe in the idea of communism, of country, and how the US is seen through the eyes of those who see the US as an enemy.

The author well enlists the techniques of a storyteller, and here, while we know the ending, we accept the suspense and endeavor to stay with the writer as he presents a large history, a large territory, as he peoples a world, as he enters into the psychology of leaders—from Mao to Deng Xiaoping and including Xi Jinping who is still among us. The reader enters deeply into the dilemma of Yook Kearn Wong, his personality, the strength of his dedication, the power of his mind to know when and how to act when the time finally comes—truly a heroic man.

And how powerful it is to see the US from Yook Kearn Wong’s point of view, and to understand the complexity: how having Japan as a common enemy delayed the final confrontation between Chiang Kai Shek and Mao Zedong—and to understand Yook Kearn Wong’s belief that Mao would be the one who to preserve the sanctity of his country.

For this reader, it’s the father’s journey (a result of many, many years of interviews–of father to son…not to mention a book of his uncle–the family historian) that makes this book addictively readable. This, along with Wong’s structure, alternating his own documentation with his father’s journey. There are photographs, as well, that fascinate, and that enhance Yook Kearn Wong’s story in his determination to prove himself worthy of Mao’s Airforce, frustrated at every turn, until he finally gives up—and with great danger, makes his way to the US, to join the rest of his family…knowing by then that it was his brother’s immigration to the US that kept him from being really trusted by the Communists–resulting in his (the father’s) not being able to fight in the Korean war, and thereby saving his life. But there he is, in the US, working in a restaurant, when he was trained as an engineer, obviously a highly intelligent man—who kept his stories to himself until the interviews by his son—whose education gave him the background he needed to start to put this book together.

This is a travelogue with repeated visits, not only to Hong Kong and Beijing and the villages in the south, but also to outer regions and frontiers, cities and towns, where the languages and cultures are influenced by the bordering nations, from Harbin—in Manchuria—to Ürümqi where he, as mentioned, he catalogues the growing tension between the Han Chinese and the Uyghurs. Not to mention the layers of history Wong provides, the economic and political influences upon these various regions, along with what characterizes these regions, along with the growing presence of surveillance, how one’s speech and appearance are seen as codes, monitoring the populace, subjecting them to danger, as experienced to varying extents in the political climates of Mao and Deng and now Xi.

To some extent this is a story about the diasporic experience that is rarely told—namely what has been left. In this book, the writer himself being first generation, the immigrant story in the US is almost the negative space of Wong’s story. And here in the US, we are in a sense all diasporic, ours a nation of immigrants, except for those brought here against their will and those whose land was usurped. Those who founded this country, the original immigrants, came as colonizers, committing the original sin, it has been said.

What looms large here is what Yoon Kearn Wong left, namely an identity, and a home that will in his heart remain his home; even as it remains a home to which he can never return, except to visit. and this can be seen as metaphorical—for the people of a country are subject to its history, and to the strongman/leader, if they are a dictatorship. Among everything else this book offers is a cautionary tale, showing just how brutal are the constraints of a non-democratic country upon the bodies and souls of its citizens.

About the reviewer: Twice a Pushcart nominee, Geri Lipschultz has published in Terrain, The Rumpus, Ms., New York Times, the Toast, Black Warrior Review, College English, among others. Her work appears in Pearson’s Literature: Introduction to Reading and Writing and in Spuyten Duyvil’s The Wreckage of Reason II. She has an MFA from the University of Iowa and a Ph.D. from Ohio University and currently teaches writing at Borough of Manhattan Community College. She was awarded a CAPS grant from New York State for her fiction, and her one-woman show (titled ‘Once Upon the Present Time’) was produced in NYC by Woodie King, Jr. Her novel, Grace before the Fall, will be published by Dark Winter Press in September 2025.