Reviewed by Amilya Robinson

Reviewed by Amilya Robinson

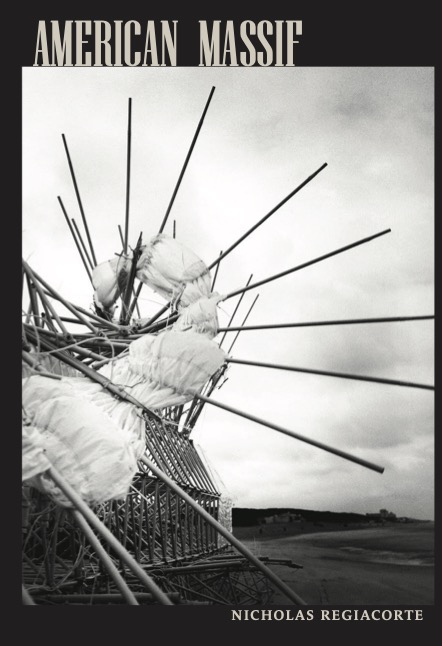

American Massif

by Nicholas Regiacorte

Tupelo Press

Paperback, May 2022, ISBN: 978-1-946482-70-9

Remarkable poet, Nicholas Regiacorte, whose poems have appeared in 14 Hills, Copper Nickel, New American Writing, and many more, stuns in his book of poetry, American Massif. This imaginative narrative follows the perspective of an American Mastodon as he navigates evolution, his human spouse and children, art, philosophy, and the many unfurling landscapes of the world. At a time when the focus on identities has become so crucial, when advocacy and education on the state of the world are so vital, Regiacorte’s work is more consequential than ever. Both viscerally human and uncannily inhuman, American Massif is an illuminating and clever collection of poetry for the ages.

There are moments within this work where I find it hard to separate the man from the mastodon, but I suppose that’s the allure in it, to follow the narrative of a being that is not quite human nor beast. In “American Mastodon wades through security,” the prehistoric narrator recalls the men there “wanding [his] / earflaps for IED’s” and “probing” him as he feels “the pressure / build on [his] spine like to birth / and steps / underfoot…” (4). He persists through the violation in order to see his mother who “invented the Pietà with those flaking / palms / her nerves burning inside out her hands / flaking open / and bleeding…” (4). Eventually, the mastodon calls for “Mercy / mercy yes we’ll show you some / mercy sir / right away right this way” (4). The language used in this poem really attempts to evoke this feeling of otherness. That this narrator does not belong here, that his appearance makes him more subject to suspicion. Regiacorte doesn’t say it explicitly in this poem, but there’s an uncanny resemblance to the treatment of marginalized individuals in our reality. In another instance, the narrator “makes a grocery run,” coming across a flag that reads “‘If this Flag offends you / then you / need a history lesson,’” and admits that “I want history / to lessen to lower my chin permanent / where this one / strap of muscle’s been waiting eons / in my jaw / to grow taut again tie my brain up / tight in / a sheep’s skull nearly / thinkless” (39). Again we witness the mastodon observing very real, very current issues within our society like the spreading of misinformation, the persistence of ignorance and historical brainwashing. The anger and frustration behind the mastodon’s reaction is all too relatable, the situation all too ironic and familiar.

I often found myself drawn to the different spaces Regiacorte takes us to with the mastodon. In contrast with the previous poems, “American Mastodon contemplates himself as an art object,” feels exactly how I would expect a book of poetry centering a prehistoric creature to be. In this poem, the mastodon tells us “They pursued me / how unassuming their spears / but straight / ribwise & sharp how admirable / their cause / I imagine & industry in quartering me / employing every piece / tail to trunk eye ears my ivories of / course into which / they might (one day) hollow out / architectures / carving little ivory baldachins / over miniature / ivory alters delicate cups / over invisible / ivory crypts…” (5). This landscape takes us back to the time in which the mastodon truly lived, in which early humans would have hunted him for food. In contrast, the mastodon seems to take with him a fragment of his modern knowledge, a vision of the future where his body is taken apart, where his ivory has become an inhumane luxury. Even as Regiacorte transports us to different times and places, the mastodon is connected to all versions of himself, a being that does not exist in one time without influence from others. In a style that I feel connects both the mastodon’s presence in modern society and his presence throughout evolution, Regiacorte unveils the past as it quite literally burrows beneath the house the mastodon finds himself in. In “Grotto Expanding at an Accelerating Rate,” the mastodon observes “Pieces of ceiling [fall] revealing / a cupola,” he “[scrapes] at a bubble / in the wall and [finds] signs of a fresco— / a golden calf,” and his wife “[pulls] up a tile / and [finds] another Tomb of / the Diver. [Moves] the refrigerator— / there were papyri stuffed in the crevices” (22). I fell in love with the content of this poem and the way Regiacorte masterfully organizes his imagery. The visuals of ancient art and history gleam so wonderfully against the dreary backdrop of the present-day house.

The narratives that appealed to me most, that scratched at those vulnerable bits on the inside, were the most intimate moments between the man/mastodon and his family, his lover, or even in those moments with himself. “Someone will / doubt my right to just be / so large,” the mastodon tells us, “Be the elephant in the room / if you want only don’t be / that one,” (9). This part of the poem reminds me of that first one back at airport security. But there’s more rebellion in the words written here. There’s a defiance against bending to the will of others who don’t accept you. The mastodon describes himself as “the only Pleistocene / in a loving but / Holocene house,” a house in which “a suppressed laugh / sob growl makes / the whole frame shrink / in around // the unexploded shell / of me— // when chairs stutter back / from the table // dinner goes pale in each dish // floorboards / down the hall choke / on word of // my unsecret and self- / immolent / wish // —everyone’s face / even the baby’s / ruddied with love and / terror” (9). Regiacorte does a brilliant job of portraying the mastodon as this (literally) larger-than-life character with so many feelings and thoughts and expressions, that he simply can’t contain them. And when he finally does get to let them all out, there’s an overwhelming sense of vulnerability exposed to those closest to him. It’s such a vivid scene in this poem, one I imagine passes by in slow motion before time freezes and the mastodon is left with only his free-flowing thoughts. In “Beautiful Curtains,” the mastodon describes watching the growth of his daughter in a poignant, vignette-like manner. “Our child is not born / green,” states the mastodon, “I watch her sleep in our bed / when she is an infant. In the morning / she is not green, but alarmingly / aged eleven years. She says, Dad, I’m ‘ fine. Can I go out? // After the screen-door slams I turn / to look up through sink and sycamore light. / She is in her mid-twenties and holding up her own baby. / We didn’t even name her. I’m sorry. I know. / But the light, for what it’s worth, she is / dancing in pure light // We are suspended in an observation / but we are not dead / and our love-making is unlike any love / of the dead. The feel of you. We aren’t dead. Listen to me. Her name…” (61). I love the way the mastodon feels like a familiar father figure in this poem, watching with fondness and apprehension as life passes quickly and appreciating those in it. Each image flows quickly and easily into the next and the language provokes this tenseness, this apprehension of what’s to come. Regiacorte really does an impressive job of showcasing his ability to manipulate the emotions of his readers and make his own words accessible to those reading them.

I’m always curious to see how an author chooses to finish a collection of work and with Regiacorte’s style in particular, I’m not sure if I quite knew what to expect. “to a poet dying young” might be a little on the nose, ending with death as the theme, but because these poems have outlined the life and experiences of this mastodon narrator, it indeed felt like the natural end to his story. “I don’t know if death will sink / in / or expel us like air into / air / all lost or all found more / wholly,” the mastodon ponders, “And the trick was never / in your hands / one vessel into another / your life / was never in your hands” (73). Just as we’ve strapped ourselves in for a ride in choosing to read this wondrous work of poetry, we too can only guess at what the future holds, what the next flip of the page will bring. In life, it is the same. Like the mastodon, we can only hold on for dear life and cherish every moment of it as it rushes by.

About the reviewer: Amilya Robinson is a senior at San Diego State University pursuing a degree in English as well as certificates in Children’s Literature and Creative Editing & Publishing. Currently, she writes creatively for SDSU’s first all-women-run magazine, Femininomenon, and edits for Splice, The Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship at SDSU College of Arts and Letters. In the future, she hopes to begin pursuing her MFA in Creative Writing for Fiction.