Reviewed by Danielle Hanson

Reviewed by Danielle Hanson

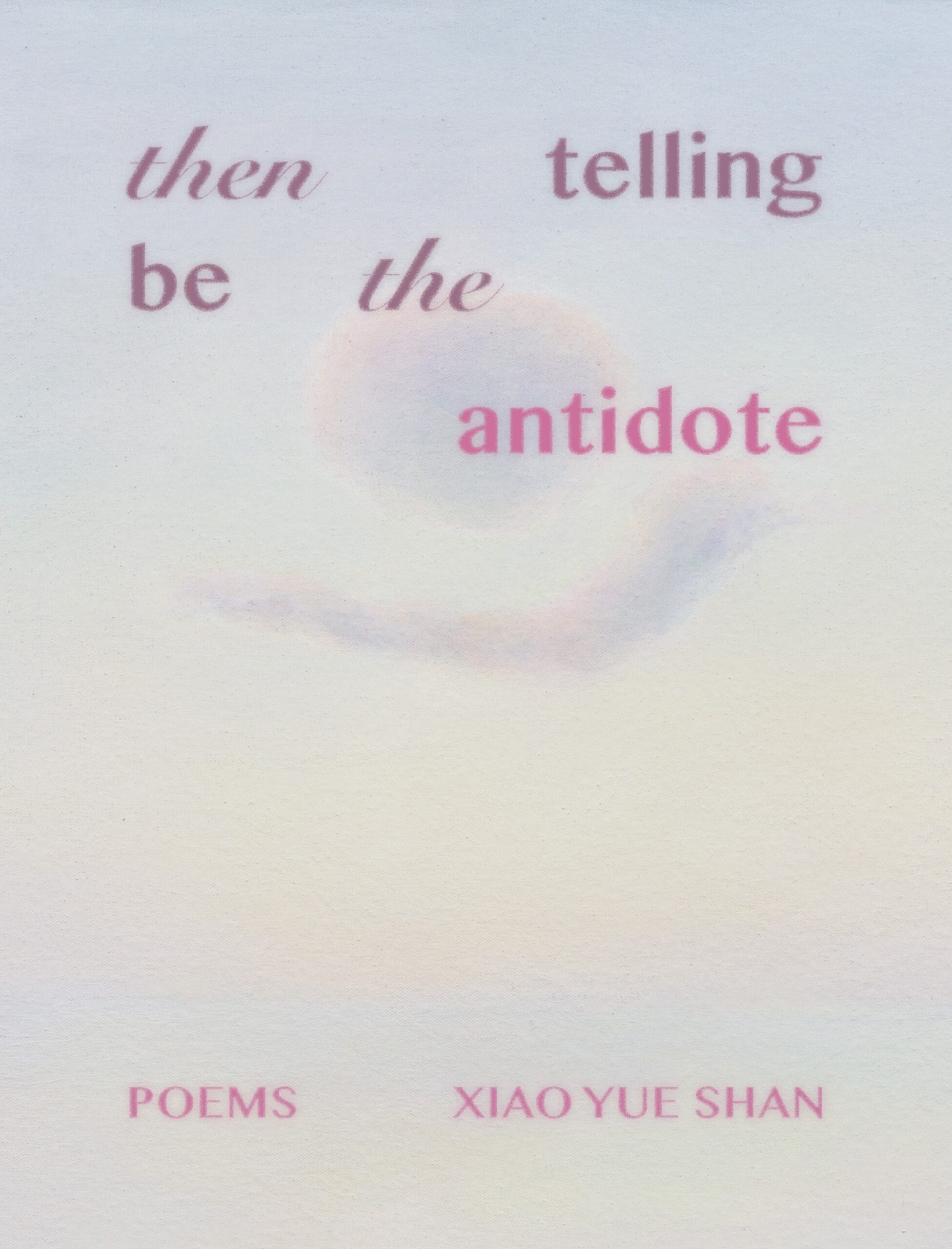

then telling be the antidote

by Xiao Yue Shan

Tupelo Press

(Berkshire Prize Winner)

Feb 2024, ISBN: 978-1-946482-92-1, Paperback, $21.95

A city is a collection. Of buildings and people and neighborhoods and animals and trash and clouds. There is no place to look at the city from the city and see the entirety of the city. In this way, Shan’s collection of poems observes the world. Each poem is a skewed viewpoint of some entirety. Her city isn’t just a physical city, although those are infused in the poems (Tokyo, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Montreal, Hanoi). Shan’s “city” is also the family, nature, love, time, dreams, reality. Place (the literal, physical city) is important, and travel among these physical realities is part of the dynamic Shan writes about in these poems—otherness, newness, migration—but these are not poems of leisure and repose, and place is just one of the elements. Of equal importance is humanness, nature, dream, time, light, water.

These elements are juxtaposed and interchanged with surreal effect. This set of equations leads to an equality among the concrete and abstract, among people and objects, dream and reality. Take, for example, how time and space are combined in “to talk with you,” “your noon and my evening congregated / touched.” And how space is collapsed in “always the clock, always the corridor, always the staircase” with the phrase “what does my voice do, but send me to you, in pieces?”

Interchangeability carries over to humans and their surroundings. See the reflection of city and human in “maps,” where the speaker avers “I want my body to stay a body. I don’t want it revealed as architecture” And in the poem, “rises in the urban population determining that each resident be allotted 1.6 square meters of personal space,” the humanscape of a crowded city is infused in piles of fruit, rich and pungent.

These are spare and open poems—gorgeous—with a beauty and longing that make me want to linger. I want to quote them all. The voice is quiet but not timid. There’s a surety and calmness of voice, even in the disruptions of immigration, fluid uncertainly, serious poverty. But there’s also urgency—lives are at stake, death is a reality. These poems explore evacuation paths filled with bodies, starvation, martial law, writers who disappeared or were censored by the state. The stakes are high. Shan is the calm voice of the emergency system telling you to not run, but GO. LIVE.

“speak, again”

we didn’t know our names

until we heard it in their mouths

we didn’t know what we loved

until we were summoned to guard it

The speaker of the poems and her family immigrate to new cities. They are in exile. Look at the tone in imagery of “the right to work”:

passage is a sudden detail in the long musical night

wherein a hand that comes in from the darkness (is it

darkness’ hand?) grants—in three serrated stamps

and the nod of a pen, a clarity of exemption to where

you came. . .

The hand that decides if they can enter and work in a new country might be the hand of darkness itself. Even the hands of day in “exile hong kong” are ominous, because they carry the knowledge that the necessity to flee is coming:

. . . this

sumnabulist language we follow, grasping at its secret knowledge

until the two gripping hands of the day pull us firmly, fallingly, to

here. the cases packed in a rush to betray nothing of their origin,

the door we closed gently behind us as if to comfort its splinters,

your hand that knifed the night to drain it of breath . . .”

The family which flees is human after all; relationships are difficult, especially between mother and daughter, as we see in “inheritance”

. . . I think I am in control

of this liminal indecision, where nothing

ends. where ruins are rebuilt with all that

is thought to have been there.

We see similar tension in “kitchen” “. . . in the kitchen years pass without / a single tender word, . . .” but this poem isn’t ultimately about conflict, it’s about the passing down of family traditions and recipes. It’s about love. These untender lessons about the tenderness of being a woman can also be found also in “decade,” a poem again about the generational legacy of women within a family, which lands with the lines “if there is such a thing as a woman’s work—that. / the using of what was given, to brave what was not.”

The humanity is evident and stunning in these poems. But the people portrayed are often behind a language/emotional veil of environment—like a window or a stand of trees. These are not poems of confession and direct emotion, as evidences in “the right to work” with the lines “work: the sifting of the possibilities of the world / thickly through the self, into fact.”

One of the most powerful tools used by Shan in these poems is the ability to surprise the reader, often through startling imagery and language. Things are weird in these poems, and that weirdness allows us to feel an emotional truth. As in this passage from “the swift light against your face is beautiful:” “there in the long field of doors / you too are catching up on days left behind” We’re in nature, then city, then human, then time, all within a single sentence. Similarly, in the poem “ideogram of morning,” rooftops are written like fiction, the day is between our teeth, the humans are witnessing their own timeless creation myth. What does time even mean when we can watch our own origin? In other poems, comfort is caught in traps, and the wind pauses to listen to the speaker and her lover. Similarly, the poem “speak” concludes “I wake up with black powder in my mouth / how did I get here in my mouth.” The speaker has the ability to be outside herself in order to see herself. Time, identity, space are malleable and shifting.

This intertwining of elements isn’t confined to time. In “the right to work” where Shan shows tells us the emotional truth of moving between cultures with a metaphor of running water, unable to capture and shifting/moving constantly: “everything, / even countries, were echoing through us like stones / through water“ And in these passages from “the coming of spring in the time of martial law”

. . . my mother fingered a ripened

bowl of hot water, carving out upon its surface the lines

by which our family would occur. . .

. . . children

rose like night-fires amidst decades in which no one spoke

above a whisper. . .

. . . each night we soothed time as if it were newborn,

as a song about marigolds prayed through the radio. . .

Shan gives us a rich emotional world where countries flow through the speaker’s family like water—hard to hold and shifting their environment—and where the family, with fire children, can be carved on water itself, which is ripened like fruit, in a night that is human. Similarly, in “looking twice”:

in a green walk-up behind the Sumida river, there’s

a mattress on the floor, supplied in ivy. and through a window

no one can see into, there are hours, carved from a night

translucent. inside them, a room where, between 4am

and your shoulder, I saw yellow . . .

It keeps going with this intertwining of nature/human/time. The mattress is on the “floor” of nature. It is “supplied” with ivy. “4am” and “shoulder” are equated. This is a marvelous world in which to talk about love, and the unstabilizing feeling of being in it. The poem ends with “holding still the gentle matters of love, as if a dream / had finally—after a terrible struggle—escaped the mind.” Wow! I love that dream so much and hope it flies far. Shan writes exquisite love poems. Her dreamlike surreality forces the reader to forget every clique they use to make sense of love. Take, for example, the ending of the poem “modals of lost opportunity” in which Shan serves us the image “the light will go dark as the door closes, slowly, / slowly, fever, warfare, yet nothing arrests time / as love does.”

Shan keeps the reader off-balance, surprised, delighted so that she can lead us wherever in the world she wants, “where the night never outlasts sleep. where, on the most distant, / nameless shores, we stay waiting, patient for ourselves to arrive.”

About the reviewer: Danielle Hanson strives to create and facilitate wonder. She is author of Fraying Edge of Sky, winner of the Codhill Press Poetry Prize, and Ambushing Water, Finalist for the Georgia Author of the Year Award. She is on the Editorial Board at Sundress Publications and teaches poetry at the University of California, Irvine. You can read more about her at daniellejhanson.com.