Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

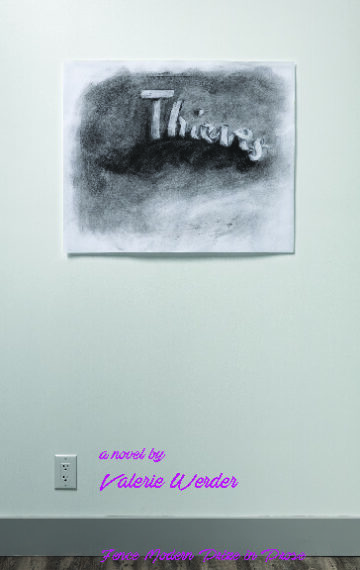

Thieves

By Valerie Werder

Fence Books

ISBN: 1944380213, Aug 2023

We live in an increasingly uncertain world, where the relationship between words, truth and reality are continually shifting. We now know the self to be a complex interaction between microorganisms: dynamic, collective, shaped by culture, events, patterns, and even trauma experienced now and in our family histories. In her debut novel, Thieves, Valerie Werder leans into the illusions we hold of the self, playing with notions of construction, art, language, and objectification. Valerie is the protagonist in Thieves, hired to provide the “voice of the gallery” for a high end art gallery. She produces gallery catalogues consisting of a range of fabricated academic essays, introductions, interviews and quotations for investors who buy the artwork at high prices, not for love, but as tax breaks or investments to shunt and trade like stocks. Valerie too is commodified, her words constructing a self that is palatable and appealing. When the book opens we learn about her shoplifting “game”, her attractive friend and co-conspirator Ted, and her soul-destroying job which she walks out of but we also know, from the start, that Valerie has already left her job and is on “sabbatical” creating something coherent – let’s say a character with a narrative – out of the shards of her chaotic life.

Ostensibly Thieves is Valerie’s coming-of-age as she works through and try to escape the constraints of her upbringing and the world in which she lives. The story appears progress in more or less linear ways, however, there is a recursiveness that functions almost as a Möbius strip where time loops around itself and the endpoint of the work is not so much Valerie’s transition as the work itself. This feels, unnervingly, like an act of self-construction, as if the work were developing and playing out only through the reader’s reading of the book recast as Valerie.doc:

It’s in the direct address, the voice aimed at a particular interlocutor—a friend or stranger, an authority, a future self seconds away, too close for she but too far for I—that language navigates between one body and the next. You infects both speakers, performs a transplant. (17)

The story walks a fine line between the surreal and metalepsis in which the book transgresses its own narrative or 4th wall by incorporating seemingly realistic elements of the construction process. Characters that seem to function as fully-realised protagonists disappear suddenly. Valerie appears in different forms that are both her and are not her. There are dream sequences, emails, diary entries, fantasies, hallucinatory fortune-tellings, and a kind of feverish, hallucinatory quality that is exacerbated by the switching of tense, use of different fonts, and repetition as the book circles back to its beginning. You have to simultaneously read carefully to pick up the tricks and follow the narrative thread even while letting go of a linear way of thinking. This creates cognitive dissonance where the reader is put in the position of participating in the commodification of Valerie even as Valerie produces real art:

Soon, Valerie could sculpt strings of words so stunning, so free, so utterly ahistorical, that she sat enchanted, transfixed for hours by their effect. Text was now a substance with which she could work, a lovely raw material, rare and precious like dark obsidian, malleable like bubblegum. (96)

Though this form of wordsmithing is presented as fake or con like the makeup Valerie steals – glitter on the cheeks, or a social media profile, it’s also the case that the writing in Thieves is often beautiful and that this beauty is an art in itself. The writing flows melodically, often taking on a poetic quality: “The last light of the day melted into pools of liquid gold on the horizon and then, there, gone.” (49) That the work undermines that beauty by forcing us to question the function of these words as drivers of commercial activity (after all, even a book needs to be sold, the relationship between the words and their signifier doesn’t change the linguistic beauty or their impact on the reader. If the sunset doesn’t exist, the description of it doesn’t become less beautiful. It’s an interesting conundrum which is also part of the complexity of Thieves.

As the above example shows, Thieves covers a lot of ground, exploring such things as the commodification of the female body, notions of creativity and artistic consumption, desire, family, and what it means to be alive or not in this world, all themes which continue to be relevant and in many ways in flux through the development of AI, social platforms and the way that our economies function. One of the most overt themes is the notion of thievery. Early on, the book situates us in the first person perspective (which shifts later) of Valerie as she’s corrupted into shoplifting by her sister Julie. This kind of thievery is rooted in societal notions of beauty and desire taken to what feels like a logical outcome:

I watched Julie’s reflection in the mirrored ceiling above Cosmetics. She was right. Although the cheek shimmer was imperceptible, it had somehow transformed her into the kind of girl who should be pausing before the L’Oreal display, considering a Ravishing Red, turning it around in her hand.” (24)

The book continues to extend and explore these ideas of consumerism, theft and beauty through sexual desire, love, and literary theory. In many different ways, from Valerie’s own transitions, relationships, experiences and work – both paid and creative – Thieves explores how we determine, create, assign value to the self or to others, and the relationship between those things. Much of this is done with a great deal of humour which is woven, in a perfectly deadpan way, throughout the text. For example, the way in which Valerie relates to her mother Susan – a woman who sits at the periphery of the story urging Valerie in the most ordinary way, to make herself appear more attractive:

At her mother’s urging, Valerie had been adding lines to her resume for as long as she could remember: piano lessons and travel and volunteer work and sports at which she’d been awful made her an attractive college prospect; alliances with high-profile professors, internships, and summer courses (and, of course, the boat-load of loans that made all this possible) made her an employable worker. Susan thought these activities and lessons were excellent for her daughter’s self-esteem. Valerie considered adding further line items to the resume, expanding it to include her uncertainties and worries, her defining neuroses, the instance of her birth and her ultimate trajectory towards death, the quick burn or slow decay of her body, the moment in which any matter that once comprised her ceased entirely to exist, eaten by bacteria and cockroaches and mushrooms. (93)

There are many such humorous moments that arise out of Valerie’s self-awareness, or through the way in which she second guesses herself, or via the many relationships she has in the book with her sister, her friends, and perhaps most insistently, her male partners, both of whom pale out of significance in different ways as the book progresses. Thieves defies categorisation and doesn’t really resolve, or maybe it does – I won’t provide any spoilers here. What I will say is that Thieves is a daring, powerful and exciting book that will challenge a reader’s notions of what makes for art, fiction, what makes for a self and the many different types of selves and subjectivities that are presented.