Reviewed by S. C. Donnelly

Reviewed by S. C. Donnelly

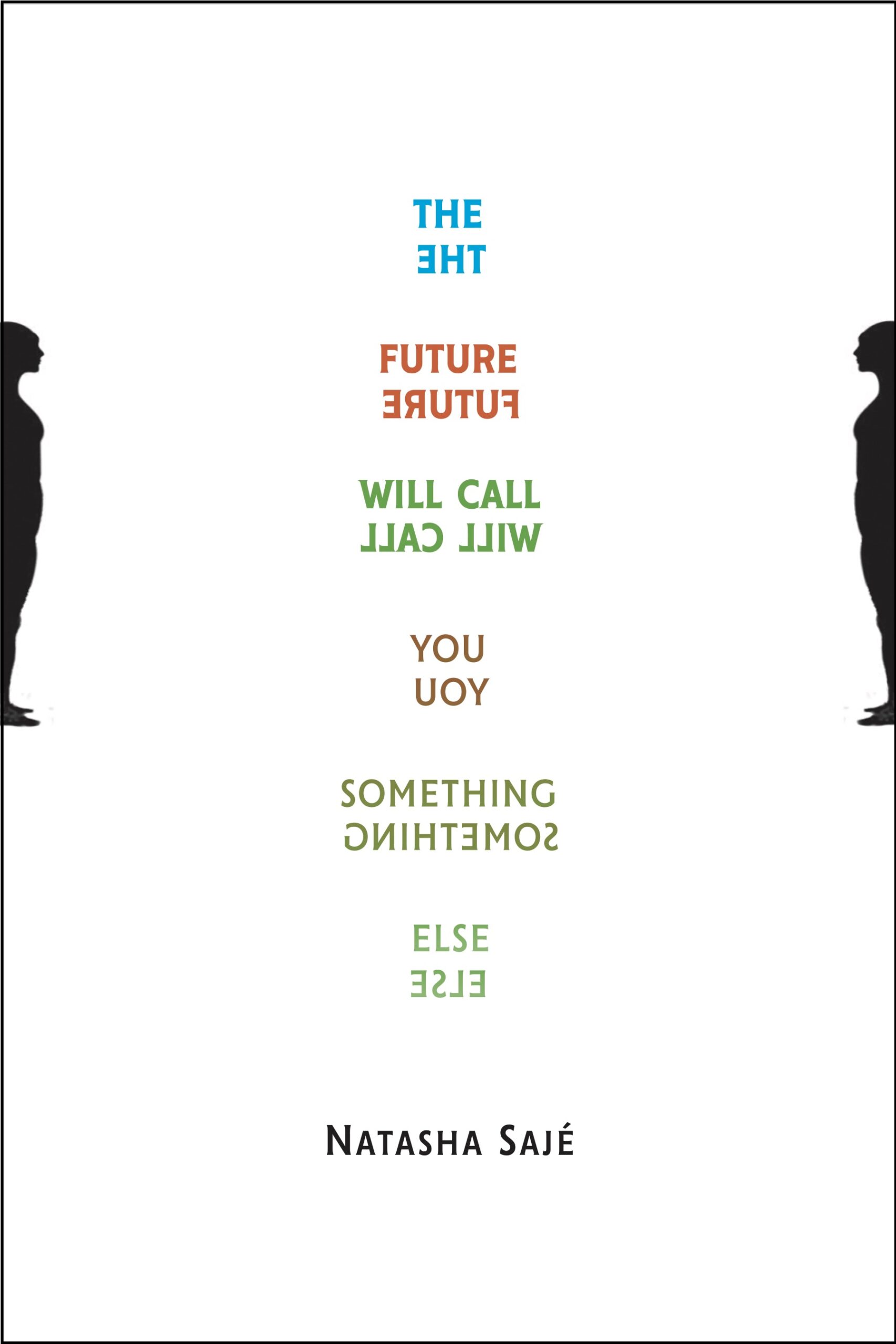

The Future Will Call You Something Else by Natasha Sajé

by Natasha Sajé

Tupelo Press

Sept 2023, ISBN: 978-1-946482-73-0, Paperback

In the opening poem of Natasha Sajé’s The Future Will Call You Something Else, the speaker observes that “[e]ach of us has things we must turn away from,” an idea affirmed by headlines in any daily newspaper. While there is much we might like to wish into nonexistence, Sajé’s collection, published by Tupelo Press, insists that we not do so, and in several poems, raises the specter of just what happens when we do.

Indeed, these poems directly address, often in epistolary form, difficulties relating to the environment, health, relationships, and identity. Titling some with a simple “Dear ___, ” Sajé speaks to an array of people from Caitlyn Jenner and Alfred Hitchcock to objects and ideas, such as artifacts, alcohol, and the apostrophe. In each of the five sections of the collection, she points to the limits of our control—as the title suggests, whoever we think we are, the future will see us differently. Yet, Sajé encourages these difficult conversations because through language we have the chance of being heard, and for better or worse, the reassurance that we belong to the world.

Sajé takes on timely topics, such as humanity’s critical relationship to nature. In “One Bud To One Tender Leaf,” the speaker, a tea bud, addresses a leaf, illustrating the connection shared between all parts of nature: “each body’s language of sinew and bone / touching other worlds”. Such interconnectedness is found again in the poem “Mitti Attar”: “still the smell of rain on dry earth / asks me if I could be every drop / …the smell asks me / not what I want / but what I am.”

Despite this connection, Sajé points to our failure to take care of this relationship. In a darkly funny poem, “Gradual,” she opens with the epitaph from the film, The Graduate: “’Just one word…plastics,’” and then intersperses prescient lyrics from Simon and Garfunkel in italics:

I wrench and cut the clear thick film—

Envisioning its path to trash. And next?

The hiding place where no one ever goes.

This stuff gets smaller and smaller…

Micro to nano to who knows what.

Every way you look at this you lose.

The poem ends noting that while “sapiens means wise. / The future will call us something else.”

The poems here are also deeply personal. Sajé is particularly poignant when writing of grief. In “Spiral Jetty,” having visited Robert Smithson’s earthwork sculpture in the Great Salt Lake, the speaker will not return as the sculpture will largely remain the same in contrast to her mother:

The first time I knew my mother

Tired of being in her body

Will soon stop eating

Will stop looking at me with longing

A longing I’ll never again not satisfy.

The pain of witnessing others’ suffering and the inability to help is raised again in “Dear Alfred Hitchcock, in a Dream,” in which the speaker dreams of her senile mother “and the drink / she might need and can’t ask for. / And then I’m sitting up in bed / as if on a playground bench, with my back / to a jungle gym covered with crows.” This sense of doom is turned back onto the self in “Notes on Elegy” where the speaker likens the illness in her own body to a banyan tree whose:

roots grow up and down

as well as sideways

with hovering

humming and crawling creatures

packed as if into a small city zoo

but free to wander

Like the creatures in a zoo, it is both easy and gratifying to lose oneself in Sajé’s surprising, yet crystal clear imagery. In “Dear Utah” she describes “the townhouses jammed into / crevices of valley like aphids on a leaf.” In “Apostrophe,” the speaker describes the punctuation mark as “trivial as lint / a currant in a muffin.” Her language makes objects, colors, and textures vividly real, as in “Brown Velvet Blouse” where she describes the color as “candlelight and a deeper honey / backs of hibernating bees.” Likewise in “Ashes of Roses,” this out-of-date color is described as “petals and rock face clad in moon / white heat cinders of extinguished fires.” Reading her poems is a fully sensory experience whose lines beg to be read aloud.

In the world of things we wish we could ignore, Sajé powerfully explores the reality of what it means to be a woman. In “Dear Roe v. Wade,” the speaker begins by saying, “What a mess you’re in, with red states / eroding you like sand under a power / wash of illogical laws…” and ends by speaking of a woman’s “gendered state, her malady.” Womanhood as malady is reiterated in “Dear Caitlyn Jenner”: “It’s quite a dream to have a body that / does not get in the way of who we are.” Again in “To the Phaistos Disk,” the speaker notes that even as a young woman “I remember my regret at being female / and fearful of a stranger.” Any reader who identifies as a woman will feel the truth of these lines reverberate in their bones.

In Sajé’s understanding, being simultaneously a threat and threatened is at the core of our existence. With such a bleak outlook, why not surrender to the reality of our limited control and give up? Sajé’s answer is simple. We matter, not because we necessarily make a big impact, but because we try. Sajé uses the role of a writer to illustrate her point. In “Dear R” she addresses an unnamed writer stating, “You make fiction, / I make poems, gathered into books few / people buy.” Yet, in “Palette” we read of a poetry teacher who made her “feel a pull like gravity / But from the sky.” And in “Reading” she describes how

neurons coax

words like insects

grant them legs and wings

a swarm that rouses me

For Sajé, words matter—even if they are unread or unheard. In fact, in the metapoem, “Dear Jolene,” the speaker admits that:

I’ve written letters to others who won’t write

back…

spiliing secrets in poems…

…fearing all the while

that the worst thing in life might beto not be known at all.

It is in expressing our ideas that we are known to parents, friends, lovers, to nature, to where we live, and to ourselves. In such expression we find meaning and purpose, regardless of how we are perceived now or in the future.

About the reviewer: S. C. Donnelly is an English teacher and tutor in the Boston area, working with students ranging from middle and high school to adults recovering from addiction. She is a former editor of the Colorado Review and was a Tupelo Press 30/30 poet in 2022. She has written numerous online book reviews, and most recently, her poetry has appeared in The Summerset Review, Gyroscope Review, and The Amethyst Review.