Reviewed by Robert Cooperman

Reviewed by Robert Cooperman

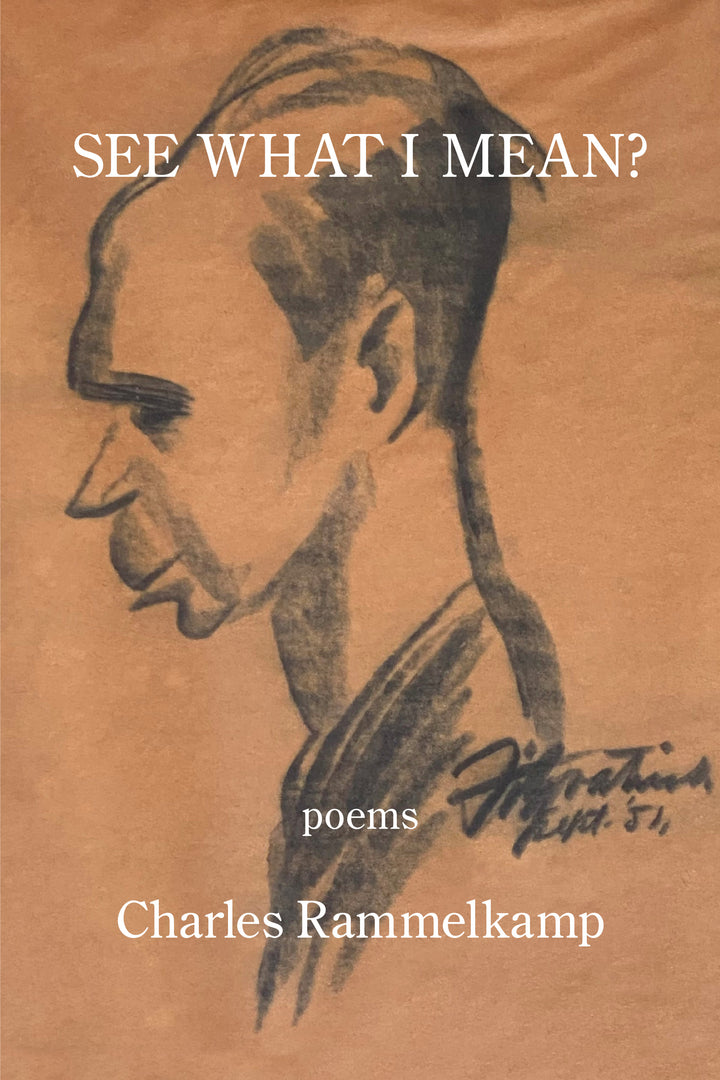

See What I Mean

by Charles Rammelkamp

Kelsay Books, $23.00, 137 pp, Oct 2023, ISBN-13: 978-1639804474

To read Charles Rammelkamp’s latest collection (of mostly poetry and some flash fiction pieces), See What I Mean, is the aesthetic equivalent of strolling through a great and gigantic department store. Think of Nieman-Marcus or Selfridge’s of old, just a cornucopia of treasures you’ve got to try on or try out, and take home with you. Every department offers different treasures. There are pieces about Robert Scott Falcon, the doomed Antarctic explorer; about the murderous Tulsa Race Riot; about sweating out the Army draft during the Vietnam War; and in a lighter vein sex, drugs, rock ‘n’ roll; and of course Rammelkamp’s passions for bird watching and yoga.

Rammelkamp is equally at home with personal and persona pieces. Both sets ring true, but the persona poem, “The Cover Up” is probably my favorite in the collection. It’s told from the point of view of a Mr. Williams, a fictional Black high school history teacher in the 1950’s or ‘60’s, most likely, telling his Black students about the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 and how it wiped out an affluent Black neighborhood, which was covered up, never discussed in most history books, in an attempt at racial erasure, sort of a forerunner of Governor DeSantis’ attempt to obliterate anything from history that might possibly make white students and white people, in general, feel uncomfortable, God forbid. One of Mr. Williams’ students, Don Ross, a pool hustler, challenges his teacher with, “‘How come don’t nobody know/nothing about it, Mr. Williams?’” And this is the truly brilliant aspect of this subversive speaking truth to power poem: the lie by omission has permeated so deeply that even the inheritors of the horror don’t believe it, since if it did happen, the reasoning goes, surely it would’ve been written about. But as it happens, Mr. Williams isn’t a mere purveyor of a fast receding-into-the-past act of horror. He was there, he was a victim, as a teenager, of the riot:

I watched a white boy running from our house,

a fur coat belonging to my mother

clutched to his chest like the pelt

of some animal he’d just killed.

Indeed, political and social divisiveness is one of the major themes of the collection, as in the poem “AuH20,” otherwise spelled as Goldwater, as in Barry Goldwater, the failed (thank God) 1964 presidential candidate and probable godfather of the crazed conservative wing of the Republican Party. When Goldwater ran against LBJ emotions ran even higher, almost murderously so and infecting one generation with the feuds and hatreds of the one that went before, as the speaker of the poem lets us know:

‘The cocksucker’s voting for Goldwater,’

I pointed an accusing finger at the bumper sticker

adorning the Dodge Dart’s chrome fender.

The one on my parents’ Studebaker read:

All the way with LBJ.’

And as the narrator, at age fourteen, continues, “All we really knew about politics/was our parents voted Democrat,/and Republicans were uptight assholes.”

But there’s a lighter side to See What I Mean, and it’s evident in poems like “The Vending Machine Tango,” which begins with the apparently verifiable premise that on average vending machines kill “thirteen people every year.” What follows is a “battle to the death” between the narrator and a vending machine with a mind of its own:

I plunked my coins into the slot,

selecting the letter-number combination

for the package of Fritos,

only to watch it get stuck in the coils

like a fly trapped in a web

behind the aquarium window,

as if the snack machine were flipping

me the bird.

I crack up over that final image every time I read the poem, but before then we’re treated to the homicidal vending machine falling on our hero, who has to be pulled out from beneath “the fat lady,” and then the final insult, the machine still wouldn’t give up that desired, that heavenly lusted after bag of Fritos to our protagonist.

Humor mingles with and amplifies the horrors of history in “Andrew Jackson’s Parrot,” a poem spoken by the potty mouthed bird himself, who has a gimlet eye for the atrocities committed by the president when it came to the removal of the Cherokees via the Trail of Tears. It’s clear who the parrot, and Rammelkamp, are siding with, when the poet has the bird proclaim to Jackson,

‘The ‘Indian Removal Act’ should be shoved up

your useless asshole every fucking second

throughout eternity,

and I hope it hurts like hell.’

History is also on the parrot’s side, Jackson no longer seen as a paragon of rough-hewn and rugged American individualism and populism. Still, it’s nice to hear the reprimands of history spoken in such plain and scatalogical language.

If there’s a set piece that can stand alone in this collection it’s the series of poems spoken by and about Karl van Beethoven, the nephew of the great 19th Century composer. The two had a contentious relationship, Karl indignant that his uncle sued to get custody of the boy away from his mother, who may not have been a saint and an angel, but did love her son. And while Karl acknowledged he lived a lot softer with the genius than he would’ve with his frequently impecunious mother, the younger man resented being separated from his mother and resented too Beethoven’s attempts to make a musician of the kid, who apparently had no aptitude whatsoever. Rammelkamp plays on these resentments and frictions to create a series of poems that are at the heart of the collection, as in the first poem in the cycle, “Karl van Beethoven Considers Suicide.”

I was ten years old

when my Uncle Ludwig became my guardian,

accusing my mother of murder,

denouncing her as a whore,

even though tuberculosis killed my father.

It’s also the old story of the normal, the average having no sympathy or patience for or understanding of the genius. This is what Rammelkamp has Karl scowl in regard to his uncle’s deafness in the next poem in the sequence: “The Heiligenstadt Testament.”

Of course, you can almost hear his arrogance

when he writes about “the one sense which ought to be

more perfect in me than others.’

He could be so infuriatingly smug.”

What a delicious literary emporium See What I Mean is, with treasures waiting to be unearthed and read. In this age of the hermeneutic and precious, Rammelkamp gets down to the itty-gritty of poetry and existence using the language of real people to help us see the complexities and complicities of our lives.

About the reviewer: Robert Cooperman has taught composition and literature at the University of Georgia; Bowling Green State University, in Ohio; and the University of Baltimore. He’s also led various poetry writing workshops. Cooperman has had more than twenty volumes of poetry published, among them In the Colorado Gold Fever Mountains (Western Reflections Books), which won the Colorado Book Award for Poetry. The Widow’s Burden (Western Reflections Books) was the runner-up for the WILLA Award from Women Writing the West. Draft Board Blues (FutureCycle Press) was named One of The Ten Best Books by a Colorado Author for 2017 by Westword Magazine. My Shtetl won the Holland Award from Logan House Press. Cooperman’s most recent collection is Reefer Madness. In addition, Cooperman’s two most recent chapbooks are Saved by the Dead (Liquid Light Press) and All Our Fare-Thee-Wells (Finishing Line Press),