Reviewed by Marc Zegans

Reviewed by Marc Zegans

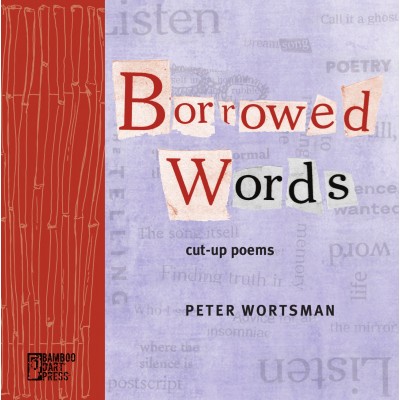

Borrowed Words: Cut-up Poems

by Peter Wortsman

Bamboo Dart Press

October 2022, Paperback, 64 pages, ISBN-13: 978-1947240575

Peter Wortsman, a writer whose work travels fluidly between fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and works for stage delivers in Borrowed Words a tightly crafted, sharply revealing collection of poems whose elements have been cut from other texts. Wortsman’s book is far more than a loose assembly of cut-outs connected only by method. It is a thematically related progression of wisely spare poems that plumb the possibilities and limitations of making meaning with extant language by recycling word and phrase that have tended toward numbing familiarity. Wortsman describes this process as “plowing words back into the mulch of meaning,” and the description is apt.

This poet’s cut-up poems, generated mostly during the lockdown phase of the pandemic, when he felt “cut-off [like a] … modern day monk languishing in the solitude of my cell…” find their roots in Dada poet Tristan Tzara’s méthode découpé, and shares scissors with William S. Burroughs’ cut-up method by which the gunman-junkie-novelist made new poems from old material. Wortsman’s approach differs though from his forbears. Central to both Tzara’s and Burroughs’ programs was production by chance encounter—Tzara advocated drawing cut-up words from a hat; Burroughs cut pages into sections, rearranged them, and sought out interesting juxtapositions. The products of these chance operations intermittently provided revelatory insights and proved capable of expanding past poets’ oeuvres by rearranging their language in a manner reminiscent the Musikalisches Wurfelspiel, or musical dice game, attributed to Mozart by which one could compose a near infinite variety of waltzes from a small body of musical text.

In Borrowed Words, rather than relying on chance as a generative device, Wortsman reads his source material prophetically, scanning texts, selecting words and phrases that attract his attention, and turning these to his ends. The poet’s intuitive means of releasing possible meaning in much the way a divining rod douses for water—an attraction he describes as “magnetic imminence”—is vibrantly illustrated in the poem “Self in Rubble, which completes the main body of Borrowed Words’ text. “Self in Rubble’ fashions a skeletal figure from cut-out fragments of text whose surfaces are more extensive than the words they will contribute to the poem. Drawing from these glued to the page ostraca, Wortsman elects then connects the poem’s language with black marker. (Plate 1).

Plate 1

The resulting disarticulated figure suggests a scavenged body, its form and inner map reminding me of work found in artist Jean Dubuffet’s art brut cycle, L’Hourloupe, particularly Coucou Bazar, a performance piece presented in the theatre at the Guggenheim during a 1973 retrospective of Dubuffet’s work. “Self in Rubble” bears formal similarity to Dubuffet’s constructions, and both writer and artist employ black line to circumscribe and connect interior components. More significantly, the poem reads visually as art brut—its picked-bones shapes and use of grafitti on previously printed text to foreground his chosen words, cut to the raw.

The bareness of cut-up lines glued to wrinkled sheets lends vigor and urgency to Borrowed Words’ individual pieces, establishing a vital tension that animates the work. The immediacy, tactility and crudity of the collection’s glue-marked reconstructions implicitly signal a primitivism that a reader will expect to carry into the content of the written text. Nothing could be less true. Wortsman’s selection and grouping of the material that forms each poem is sharp and sophisticated; his cumulative development of meaning through the sequence of poems is masterful, and his mode of presentation astutely achieves dynamic tension between textual texture and semantic substance. By defeating intuitions implied by irregularities at the edge, Wortsman’s cut-up poems arrest attention and makes words fresh.

His project works in significant part because there’s something delicious about experiencing physically cut and pasted words on a page, so different from the product of the abstracted function we now perform on our computers without a tingle of titillation. The physicality and visual variety of cut-and-paste actions have been reduced on screen to their efficient minima: We select, we mark, we click cut, we locate the cursor, we click paste, the uniform text is flatly inserted, and history is erased by the continuity of like characters marched in ranks across the visual field.

By contrast, arranging cut-outs, glued by hand to a rapidly wrinkling sheet, demands technique: scissors are involved; the slip of the hand carries consequences—there’s no undo button; the angle of attack varies with the placement of the target word in the source text, and the gluing of phrase to sheet demands focus, visual acuity, and a somewhat steady hand. In short, a completed cut-up poem is not a digital artifact, but a thing, made animate by the stitching together of scavenged parts. Its actuality is inscribed in its rough edges, its uneven spacing, its glue blobs that extend the dimensionality of the page, and its intermingling of fonts. Even in digitally reproduced form, the presence of the live hand that made the original and the intent that governed it is palpable. Therein lies the cut-up poem’s beauty and its interest.

The notion of cut-up as hand-stitched animation immediately conjures an association with Mary Wollstonecraft Shelly’s modern Prometheus, yet Wortsman’s products are far different from the monstrous abomination that Shelly imagined would result from the excising and suturing of parts gone dead. The crucial difference derives from intent. Shelly’s is a tale of the horrific consequences that follow on her main character’s excessive romantic desire to reanimate what had been lost to the past. Wortsman’s motive in Borrowed Words is precisely the opposite, to mulch old words into soil from which new life can grow, an intent whose execution bears rich fruit.

In the collection’s first poem, and one of its shortest, “Almost a Meditation,” the poet declares

On a wrinkled sheet of lined paper

my truest essence

an assemblage of

wrestling

words

A conventional typeface transcription of this poem appears in the collection’s forward prior to its cut-up presentation in the main text. The transcribed poem memorably condenses the author’s introductory remarks, but this straight-type version feels too clean. A cruder, more visceral pulse animating the poem appears to have been lost in its translation. This sense of absence disappears the moment one encounters the rough-edged original. The glued words quiver on the page and “wrestling” as “wrested.” A visual misstep, or perhaps a clue to an implicit meaning?

The case for the latter is strong. Wortsman notes in the forward to Borrowed Words that entering the third year of COVID,

I feel increasingly cut off from the word – a telling Freudian slip: I meant to write the world, Both are true.

My slide is closely analogous. Wortsman’s words drawn from different sources do wrestle on the page. This is the agon by which the poet endows them with new meaning. It is plain fact, also, that these words—like the Elgin Marbles—have been seized. The clustered letters on his wrinkled sheets have been wrested from their native sides. Wrestling-wrested: Each is true.

In “The Way Words Look on the Page,” the collection’s second poem, the narrative line travels from the poet’s “truest essence” to the appearance of things, demonstrated by swift transitions through scattered images— “bonsai/body language/the same dreaming finger”—ending in a string of sibilants— “signs/still seeking/secrets.” These read as fragments peeking out from the layers of sediment in which they rest, creating the awed feeling of having stumbled onto an ancient cache, an experience akin to the poem’s closing words, “I THINK I’VE DISCOVERED/The Dead Sea Scrolls.”

The progression from essence to appearance to awe in Borrowed Words’ first two poems initiates both a path of forward motion and a line of connective tissue that drive and unify this scrappy collection. The mode of development, including occasional recursion, that shapes the text is more conceptual and thematic than it is dramatic. Rather than advancing by conflict, Borrowed Words evolves through a series of topical observations that yield progressive insight.

Following the transition from essence to appearance in the first two poems, we travel through time-eternity-memory-creation from silence into sound expressed as noise, dropping next into song-dream song-insomnia, and then touching the line between order and chaos that spawns complexity. Having located life at this generative edge, Wortsman’s poems dive into the nature of craft—proposing writing as deep listening, characterizing the cut-up process as the fixing of chaos on the page, and pinpointing poetry as the product of mining, the artful lie being its only requirement:

At the end of the day, all

you have to do is lie

artfully.

You can do this.

Keep going.

The notion that adroit fabrication is the necessary condition to poetic practice, coupled with the premise that poetry is mining, invites poets to find their words in the land of make-believe, a world whose entry lies in the province of play, a proposition confirmed in “Ode to/Nothing/Time.” This poem of address sings to the allure of “doing nothing with intensity,” describes the possibilities that arise with the cessation of thought and asserts that living in nothing time has been always the root of the poet’s desire. Why?

I’m not going to lie,

basically I

just like

playing.

In “The Telling,” the poem that follows, Wortsman imagines he has become the text of a story stripped to its bones:

austere

drawn on scraps of paper,

or someone else’s stationery –

artifice

scraped

raw

down

to the ordinary.

Subsequent poems discuss the content, making, reinvention, and destruction of this textual self. “Wednesday’s Wisdom” introduces faces: first, “a ghost/inhabiting/the face of it, and then, [the]

face of a younger self

like a mirror

for the future

no longer imaginable

As the poem continues, it describes how we form ourselves through story:

we tell ourselves stories,

sketches, songs, monologues,

tell ourselves other people’s stories

in order to form our own;

In “Who I see in the mirror,” the poet’s face reappears, this time signifying a falling of the mask:

forced

to be alone with myself,

my face was basically falling off

Now unmasked, the poet entertains in “Reinventing Himself,” the possibility of “…another/I…” that he might be, a speculative interlude that arrives just before the collapse of his textual self in the skeletal “Self in Rubble” that ends, save for a post-script, the collection.

The progression of poems in Borrowed Words from essence to textual identity and its collapse, contains a deep order that sharply distinguishes this book from applications of the cut-up method that rely exclusively on chance as their means of revelation. Cut-ups produced by chance operation place the generation of novel insight entirely outside the author. The best an author can do when following one of these procedures is to seize what sparkles from the dross and deliver to readers a cluster of aperçus akin to the bucket of sea glass a child might gather from a windswept beach.

Certainly, these colorful fragments can be lined up this way and that, yielding one interpretation or another, but the beauty and direct meaning of each piece is intrinsic to the object; the author can add nothing. Wortsman, who relies on intuition abetted by conscious intent, accomplishes far more. He has selected, digested, and repurposed words found elsewhere, then orchestrated their display to tell a deeply personal story, precisely situated in time, and profound in its relation of human identity to the making of texts. Borrowed words are the vehicle by which this poet has fashioned, furnished, layered, and revealed what he means to say in this engaging, emotionally rich, truly original small volume. And he has done it well.

About the reviewer: Marc Zegans is a poet, spoken word artist, and creative development advisor who helps artists, writers and creative people thrive and shine. Marc is the author of seven collections of poems, most recently, Lyon Street, The Snow Dead, and La Commedia Sotterrranea, an e-book, Intentional Practice and the Art of Finding Natural Audience, and two spoken word albums, Marker and Parker, with the late jazz pianist Don Parker, and Night Work. He has been the Narragansett Beer Poet Laureate and a Poetry Whore with the New York Poetry Brothel—which Time Out New York described as “New York’s Sexiest Literary Event.” Marc has performed everywhere from the Bowery Poetry Club and the American Poetry Museum to the San Francisco 40th Anniversary of Punk Rock Renaissance. Find out more at http://www.marczegans.com